Editor’s note: for a detailed list of resources to support development of adventure safety regulation in Iceland, click here.

On a sunny day in August 2024, a mass of collapsing ice fatally injured a tourist on a group tour of the Breiðamerkurjökull glacier in Iceland, and seriously injured his partner. The incident led to calls for the Icelandic government to strengthen safety regulations for adventure activities in the country.

Adventure providers, members of industry associations, and government leaders all expressed interest in enhancing safety requirements for adventure tour operators in Iceland.

This raised questions, however: what activities should be regulated? What should the regulations say, and how should they be enforced? How can regulations be strong enough to improve safety, but not be overly-burdensome to Iceland’s commercial adventure providers?

Lessons from other countries that have introduced adventure safety regulation can be informative. So too, can a clear understanding of characteristics of effective adventure safety regulation, and knowledge of good practice for regulatory development.

Iceland: A Strong Adventure Tourism Sector with Well-Regarded Safety Structures

Iceland starts its exploration of new adventure safety regulation from a position of strength.

In 2019, the World Economic Forum (WEF) Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report rated Iceland #2 out of 140 countries, only behind Finland, in “Safety & Security.”

Five years later, the WEF Travel & Tourism Development Index 2024 ranked Iceland #1 for Safety and Security out of 44 European & Eurasian economies.

Of the 17 enabling factors that the World Economic Forum used in its rankings—including Business Environment, Human Resources and Labour Market, Ground and Port Infrastructure, Environmental Sustainability, Natural Resources, and Cultural Resources—Safety and Security was where Iceland did the best. (Price-competitiveness is where Iceland lags behind many other global travel destinations.)

In the Adventure Tourism Development Index’s 2024 assessment of adventure tourism competitiveness, Iceland ranked in the 10th percentile—17 out of 190 countries and territories—for safety. (Luxembourg and Andorra topped the list, followed by other Nordic and European countries, and countries such as New Zealand and Canada.)

Nevertheless, the tragic incident on the Breiðamerkurjökull glacier in Vatnajökull National Park raises the question: are there opportunities to improve safety in adventure tourism activities in Iceland?

Current Adventure Safety Measures in Iceland

Outdoor adventure has been a part of Iceland for over a thousand years, since the first Irish monks and Viking explorers from Norway settled the craggy, glaciated island.

So, too, has regulation: the Icelandic Parliament (Alþingi), the world’s oldest parliament, was established in 930 CE, not long after the first settlers arrived.

Today’s Iceland has a variety of compulsory and voluntary measures regarding adventure tourism and travel experiences in the country.

Ferðamálastofa license

The Icelandic Tourist Board, or Ferðamálastofa, requires all tourism providers to acquire a license from the Board before beginning operations.

Under Act No. 96/2018 on the Icelandic Tourist Board, as a condition of licensure, a tourism provider must establish a safety plan for each type of tour they offer, with the following four components:

- Risk assessment (evaluation of risks, by likelihood and severity)

- Rules on work procedures (standard operating procedures)

- Contingency plan (incident response plan, or emergency response plan)

- Incident report (a form for recording safety mishaps)

Risk Assessment

Tour operators must use the risk assessment as a guide when selecting employees such as guides, when scheduling tours, while assessing external conditions and when choosing equipment.

Participants must be informed in a clear manner about main risk factors arising from adventure activities.

Procedures

Procedures in the safety plan must address items including, but not limited to:

- Information on the knowledge, experience and skills of the staff who are responsible for the trip

- How to respond in the event of a hazard

- How telecommunications should be handled

Contingency Plan

The contingency plan must be based on the risk assessment, and give guidance about how to respond to emergencies and other incidents.

Incident Report

Ferðamálastofa requires operators to use an incident report form, which must include details on the incident, who was involved, and the nature of the response.

A person offering organized trips within Icelandic territory is responsible for updating their safety plan regularly and as soon as necessary.

Although Ferðamálastofa requires these documents to be created, the organization does not require them to be submitted.

Ferðamálastofa does not normally review the documents for adequacy, but they can be requested, and Ferðamálastofa has the ability to levy daily fines if the safety plan is “clearly inadequate” and is not rectified within a reasonable period of time.

Ferðamálastofa also requires operators to meet insurance requirements, and provides checklists for compiling and reviewing safety plans for the following activities:

- Caving

- Coaches

- Cycling Tours

- Diving & Snorkeling

- Hikes in Glaciers & Mountains

- Summertime Hikes in Mountains

- Hunting & Angling

- Jeep, Snowmobile & ATV Tours

- Kayaking

- Museums, Centres & Exhibitions

- Nature Observation

- Riding Tours & Horse Rental

- River Rafting

Other licenses

Adventure operators may be required to obtain other licenses, depending on the nature of their activities:

- Icelandic Transport Authority transportation licenses for transport on land, in the air, at sea, or on lakes or rivers

- Offices for Health and Environment and District Commissioner licenses for accommodation and food service

- Offices for Health and Environment licenses for horse rentals

- Environment Agency of Iceland licenses for off-road driving and hunting reindeer and birds

- Chiefs of Police licenses for skydiving and carrying firearms

- Directorate of Fisheries recreational fishing licenses

Vatnajökull National Park permit

Following the 2024 incident on a glacier tour, the agency overseeing commercial tours in Vatnajökull National Park strengthened its permit system.

Permits now have ice cave tour restrictions, and have requirements aligned with Ferðamálastofa recommendations as well as specific guidance on glacier hikes and ice cave exploration.

Vakinn

In 2022, the “Vakinn” official quality and environmental certification for Icelandic tourism was launched, and is overseen by Ferðamálastofa.

Vakinn issues certifications in a variety of subjects, such as hotel accommodations and environmental systems. A “Quality Tourism Services” certification addresses adventure tourism activities.

Vatkinn provides detailed guidance in 30 categories of tourism services:

- 200 General Quality Criteria

- 201 Easy Walks in Urban Areas and Lowlands

- 202 Hiking in Mountains in Summer Conditions, Rural Areas and Wilderness

- 203 Hiking in Mountains in Winter Conditions and on Glaciers

- 204 Ski Tours in Mountain Regions

- 205 Jeep Tours

- 206 Snowmobile Tours

- 207 ATV and Buggy Tours

- 208 Nature Observation on Land

- 209 Caving

- 210 Riding Tours and Horse Rentals

- 211 Day Tour Providers and Travel Agencies

- 212 Spas and Wellness

- 213 Museums, Centers and Exhibitions

- 214 Hunting

- 215 Sea Angling

- 216 Diving and Snorkelling

- 217 River Rafting

- 218 Kayaking

- 219 Car Rentals

- 220 Coaches

- 221 Golf

- 222 Information Centres

- 223 Cycling Tours

- 224 Restaurants and Cafés

- 225 Nature Observation at Sea and on Lakes

- 226 Angling

- 227 Helicopter Tours

- 228 Ice Caving

- 229 Walks on Glacier Tongues

- 230 Venues

An adventure activity operator wishing to be Vakinn-certified must meet all the criteria applicable to its operations.

Vakinn also provides detailed written information on how to create a safety management system, including:

- Guidance on how to create safety plans, via 69-page “Safety Plan for Tourism: Guidelines and Examples” manual

- Incident report template

- Risk assessment template

- Sample contingency plans (incident response/emergency response plans)

Unlike Ferðamálastofa’s licensing system, the Vakinn structure includes a conformance assessment to help ensure that operators applying for certification verifiably meet Vakinn’s numerous criteria.

These assessments include document review and a site visit. They are conducted by independent third-party operators, of which there are currently three:

- BSI á Íslandi (an agent of the British Standards Institution)

- Vottunarstofan Tún ehf.

- iCert

These third parties, rather than Vakinn itself, provide certification.

The Vakinn system is voluntary, so operators are free to provide adventure experiences without a Vakinn certification.

Vakinn’s system has been thoughtfully developed. The Vakinn program has extensive measures to help ensure that adventure safety standards are made clear, and that operators who obtain a Vakinn certification demonstrably meet those standards.

Guidelines On Safety Matters for Tour Organizers And Travel Agencies

In 2013, Ferðamálastofa published ‘Guidelines On Safety Matters for Tour Organizers And Travel Agencies,’ or Leiðbeinandi Reglur Um Öryggismál Ferðaskipuleggjenda Og Ferðaskrifstofa.

This 27-page manual describes a variety of safety requirements, which are similar to the agency’s licensing requirements:

- Safety plan must be prepared

- Risk assessments for each trip

- Written procedures

- Contingency plan

- Incident report

The guidelines also give extensive detail on the competencies of guides with respect to specific knowledge, skills, trainings completed for leading various activities. The activities described include:

- Hiking

- Mountaineering

- Skiing

- Driving

- Snowmobiling

- Horseback riding

- Cycling

- ATV riding

- Boat tours

- Kayaking

- Rafting

- Diving

- Swimming

- Flying

These guidelines had been contemplated for adoption into adventure safety regulation for Iceland. The legislative steps to complete this were never completed, however. Conformance to these standards thus remains voluntary.

Since 2013, Iceland’s adventure tourism sector has further developed, and activities not listed in these safety guidelines are not offered in the country.

Adventure Safety Around The World

Adventure professionals and government leaders interested in exploring opportunities to advance quality and safety of outdoor adventures in Iceland through well-developed regulatory structures can benefit from the experience of other nations who have made similar efforts.

Adventure safety regulations exist in the UK, UAE, Oman, Finland, New Zealand, Switzerland, Yukon Canada and India, and are under consideration in other nations, including the Republic of Georgia and Japan.

(Other jurisdictions have certain adventure safety requirements, for example around high ropes challenge courses, climbing walls and summer camps.)

Aotearoa New Zealand

Outdoor adventure is a big part of the economy and national identity of New Zealand (known by its Māori name, Aotearoa).

In 2008, six teenage school children and their teacher drowned while gorge hiking at an outdoor education center.

Two weeks later, a 21-year-old British tourist also drowned on a riverboarding trip on Aotearoa’s Kawarau River.

The resulting pressure led the New Zealand government to develop adventure safety regulations, which are considered a world leader in high-quality, well-developed adventure regulatory systems.

The regulations require adventure operators to have a comprehensive Safety Management System (SMS), and to pass a third-party audit certifying that the SMS is adequate.

A 34-page, 7,000-word Safety Audit Standard accompanies the regulation, and describes the requirements of the Safety Management System that adventure activity operators must meet in order to provide adventure activities. These requirements address, among other items:

- Maintain and continually improve a Safety Management System (SMS)

- Top leadership must ensure appropriate resources to implement the SMS are available and used

- SMS must be developed using information about relevant laws, codes and safety guidelines

- Safety goals must be set

- Staff must comply with SMS requirements

- Operator must maintain procedures for safety communications with staff, participants and others, including acknowledgement of risk, medical requirements and complaints

- Staff must be trained on the SMS

- Risks must be assessed

- Serious risk must be eliminated or minimized, so far as is reasonably practicable

- Risk controls must be effective, checked annually, and used correctly

- Drug and alcohol risks must be managed

- Natural hazard risks must be managed

- Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) must be maintained for each activity

- Staff must be competent

- Risks must by dynamically managed (continually managed during the activity)

- Participants must be adequately supervised

- Clothing and equipment must be suitable and available in sufficient quantities

- Field communications procedures must exist

- An emergency response plan must be maintained

- An incident reporting procedure must exist

- An incident review process must exist

- Safety documents must be adequate, available, and periodically reviewed

- A continual improvement process must exist

- The SMS must be reviewed annually

- Adventure activities must be reviewed

Aotearoa’s full Safety Audit Standard for adventure activity providers can be a valuable resource for individuals in Iceland or anywhere in the world seeking a comprehensive, well-articulated set of adventure safety requirements.

Switzerland

In July 1999, 45 tourists embarked on a two-hour canyoning tour of Switzerland’s scenic Saxetenbach Gorge. A two-meter wall of water descended on the tourists and their guides as a flash flood raced down the canyon.

Eighteen guests and three of their leaders drowned.

Just 10 months later, the organization that led the fateful canyon trip had another tragedy.

The adventure operator ran a bungee jump operation from a cable car crossing a Swiss mountain valley.

There are two bungee jump locations: one 100 meters (330 feet) above ground and one 180 meters (590 feet) above ground. A short cable is used for the 100-meter drop, and a long cable is use for the 180-meter drop.

The long cable was mistakenly attached to Matthew Colemen, a 22-year-old tourist. When he jumped from the location closer to the ground, he hit the ground next to a parking lot, and did not survive the fall.

The adventure company ceased operations, and calls for adventure safety regulations were made.

But the Swiss government wasn’t interested, preferring that businesses regulate themselves.

A “Safety in Adventures” system was set up, providing safety standards that operators could meet, if they chose too.

But few outdoor adventure companies decided to meet the voluntary standards, as the additional work and cost didn’t seem to be worth it.

With low participation rates, the voluntary system was eventually scrapped. In its place, a 2010 law regulating high-risk adventure activities was instituted.

The law addressed higher-risk mountain and snow-sports activities, as well as canyoning, rafting, and bungee jumping. It requires clients to be advised of dangers, appropriate equipment management, evaluation of weather conditions, and a sufficient number of qualified staff.

In 2014, high-risk adventure activities regulations came into force, complementing the law, and instituted a licensing requirement for guides and requirements regarding safety management systems, information to participants, and competence of leaders.

A third-party audit is part of the conformance assessment system.

United Kingdom

In 1993, eight students and their teacher, with two outdoor guides, departed for what was to be a two-hour kayak trip in Lyme Bay, on the south coast of England. The wind picked up; waves rose to a meter high, and kayakers capsized and were swept out to sea.

Instructional staff were inexperienced, and did not carry a VHF radio or flares. The company had not instituted appropriate emergency procedures or trained staff in them.

When the group did not return on time, the leadership of the outdoor activity centre failed to alert emergency services or initiate a search and rescue process.

Four students drowned.

Following the incident, in 1996 the UK government enacted Adventure Activities Licensing Regulations, which were amended several times.

Requirements of adventure activity operators address a number of subjects, including:

- Providers must have a license before operating

- Operators must pass third-party audit

- Safety Management System required

- Sufficient number of competent instructors

- Leader-participant ratios

- Safety communications

- Equipment management

- First aid & emergency response

United Arab Emirates

As the world seeks to shift from oil and gas to more environmentally friendly energy sources, governments in the oil-rich Middle East seek to diversify their economies. Adventure travel is a significant part of the plans for a new and sustainable Middle East economy.

Oman, Saudi Arabia, and other nations on the Arabian Peninsula have made major shifts to build an adventure recreation sector. And risk management regulation is part of developing a robust and sustainable outdoor adventure industry.

In the United Arab Emirates, the emirate of Fujairah, which had less oil wealth than some of its neighbors, decided early on to make a significant investment in adventure tourism.

After several incidents, including a hiker’s fatal fall, a paraglider incident and the death of four rescuers whose helicopter hit a zipline, adventure professionals called for regulating adventure safety in the emirate.

The government established Fujairah Adventures, a government body to develop and regulate adventure tourism. Fujairah Adventures established a large adventure center, built trails, brought in international experts in adventure activities, and developed regulations and a licensing system.

The government recently hosted an International Conference of Adventure Tourism, where His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Hamad bin Mohammed Al-Sharqi, Crown Prince of Fujairah, Supreme Council Member and Ruler of Fujairah, presided over signing of MOUs to deepen connections between Fujairah and the global adventure tourism industry.

Georgia

The eastern European nation of Georgia stretches from the shores of the Black Sea to the snowy peaks of the Caucasus mountains, and its geography brings with it world-class mountaineering, skiing, whitewater rafting, paragliding and other adventure activities.

In 2012, two young people died after a rope jump off a bridge in Tbilisi failed, reportedly because the ropes were attached to the bridge with seat belts from a car.

In 2022, a tourist drowned on a rafting trip. That same year, a paraglider in the alpine village of Gudauri crashed into a cliff and was seriously injured. The helicopter which came to rescue the paraglider clipped the cliff with its tail rotor, and lost control.

The helicopter crashed and exploded in a massive ball of flames, killing all eight rescuers aboard. A national day of mourning was held, all paragliding activities were prohibited, and members of the Georgian Paragliding Federation called for government regulation to improve adventure safety in the country.

Viristar was approached to support developing those regulations, and Viristar staff drafted adventure safety regulations for the Republic of Georgia.

Requirements in the proposed regulations parallel requirements for adventure providers in Aotearoa New Zealand, and include, among other measures:

- Comprehensive Safety Management System

- Organization pass third-party audit before registration

- Leaders must be qualified

The government was also encouraged to support the private sector in developing detailed activity-specific safety standards, in the form of Codes of Practice or Good Practice Guidelines documents.

Japan

In March 2017, a group of 52 high school students and 11 of teachers took part in a three-day mountain climbing training experience at a ski area in the mountains near Nasu in Tochigi prefecture, some 150 km north of Tokyo.

An avalanche struck the group. Seven students and a teacher died.

Following the incident, winter mountaineering activities were prohibited for high school students, and three teachers were sentenced to prison.

In the years after the Tochigi tragedy, adventure tourism professionals in Japan called for regulating adventure activities in Japan.

The prefectural and national governments, however, were not eager to establish regulations.

The adventure tourism industry continued to advocate for adventure safety regulation, however. Outdoor professionals are working with the Nagano government to require outdoor risk management training as a standardized adventure guide training across the prefecture, in order for an adventure guide to earn “recommended” status by the government.

Other Countries

Earlier this year, Singapore published a Code of Practice for outdoor adventure activities (focusing on outdoor education). The Code of Practice is currently voluntary, but it’s planned for conformance to the standards to be a requirement in order to conduct certain adventure activities in the island country.

India and Finland have also established regulations for outdoor adventure activities.

Conformance Regimes

When it comes to ensuring that an adventure provider (or any other business) is meeting certain safety standards, one can consider three ways of assessing conformance to certain standards or requirements.

These are:

- Self-regulation, where an individual business declares it has met certain criteria

- Self-regulation by the industry, where an industry organization provides an accreditation or certification program with an independent audit, to verify that a business meets certain criteria

- Government regulation, where conformance to standards is required, and where a third-party audit evaluates compliance with requirements

Of these systems, self-regulation is the weakest. When standards are voluntary, and the industry regulates itself, the lowest rates of conformance are expected to be the result.

This is the case even when a well-developed industry accreditation system with third-party audit is in place, such as an adventure safety accreditation program, since meeting the standards is voluntary.

With government regulation, however, where meeting the standards is required, and where non-compliance can be met with judicial remedies, the best likelihood of an adventure operator meeting safety expectations is found.

This leads adventure professionals and responsible government officials around the world to see well-developed and appropriately enforced regulation as the most effective means of improving safety and quality of outdoor and adventure experiences, compared to self-regulation efforts.

Why Regulate Adventure Risk Management?

Expectations for safety and quality in adventure experiences are increasing. The way a kayak trip in the 1970s might be conducted is no longer considered acceptable today.

The adventure tourism industry is professionalizing. Adventure guides and program administrators increasingly hold a wide variety of certifications, from technical activity-specific skills to risk management, and hold advanced degrees in outdoor recreation or related subjects.

And more and more countries are investing in developing their adventure travel sector, and competing on a global level for customers.

Nations such as Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia are making significant strides in establishing highly-skilled adventure providers, well-developed venues, and adventure safety regulation, which make them increasingly competitive in the worldwide market for adventure travelers.

Developing Safety Management System Criteria

Aotearoa New Zealand’s Safety Management System (SMS) remains a global exemplar of a well-developed set of criteria for a Safety Management System for adventure activity operators.

Advances in safety science continue, however, so those interested in the most effective outdoor safety measures can benefit from staying aware of good practice standards from across the health and safety sector and the adventure industry.

Three considerations in establishing SMS criteria are worth highlighting:

- Human Factors

- Safety by Design

- Safety Culture

Human Factors in Incident Causation

When a skilled professional makes a workplace error, the mistake is usually not from a technical deficit, such as not knowing how to build a climbing anchor or conduct a t-rescue of a capsized kayaker.

Instead, errors often arise from problems with cognitive skills, such as decision-making and problem-solving, or interpersonal skills, such as leadership, communication, collaboration, or managing group dynamics.

Consequently, training adventure activity leaders in communications, situational awareness, contingency planning, fatigue awareness, problem-solving, decision-making, & teamwork can help reduce errors and the incidents they bring.

Practices such as debriefing (reviewing, processing) incidents after they occur, and providing feedback to colleagues, can support reduction in error rates.

And a Just Culture, where individuals who make a mistake are not automatically blamed and punished, but where underlying factors which might have contributed to the incident’s occurrence are considered, can support learning and improvement.

These measures are largely made possible by administrators, who establish training plans, set procedures for debriefing, and establish elements of a Just Culture.

Because of this, regulations which motivate program administrators to take these steps in there adventure-providing operation can be valuable.

Judgment & Decision-Making

There is not good empirical evidence that judgment can be “taught” to adventure activity leaders or others. Beyond baseline training, experience is not shown to improve judgment.

Therefore, to support good decision-making, program administrators can take steps to structurally reduce the need for making difficult decisions.

For example, administrators can:

- Institutionally eliminate risks (for instance, driving vehicles at night)

- Institutionally reduce high-risk situations (such as unqualified staff or medically unsuitable participants)

Administrators can also provide “decision aids,” such as

- Checklists

- Policies and procedures

- Pre-established safety briefing documents

- Strict turn-around times on peak ascents

- Third-party consult via sat phone or VHF radio

These supports can help improve the quality of safety decisions made in the field.

Regulatory structures can look not only at the skills and knowledge of field-based activity leaders, but also at the managerial aspects of supporting decision-making that can help field staff make good safety decisions.

Human and Organizational Performance

Human and Organizational Performance, or HOP, is another approach to thinking through human factors in incident causation.

The most effective personnel management system looks at all factors influencing worker behavior—not focusing on technical skills.

A manager informed by HOP principles can, rather than seeing direct-service personnel as solely to blame when an incident occurs, can ask, “How can we make it more difficult to make the wrong decision?”

Administrative principles that can optimize Human and Organizational Performance include:

- Clearly written procedures

- Clear roles & responsibilities

- Procedures well-matched to real conditions

- Procedures written with activity leader input

- Decision aids (e.g. turnaround times, site closure, and ‘stop or postpone activity’ rules) to reduce need for difficult safety decisions

- Psychological safety (ok to speak up, raise concerns, make errors without retribution)

- Workload management

- Fatigue management

(For more on HOP, Norsk Industri’s “Safety, Leadership and Learning—A Practical Guide to HOP” offers a compelling explanation of the theory and practice of Human and Organizational Performance in the workplace—in the heavy industry context specifically, but with universally applicable principles.)

Well-developed regulation can seek to support the inclusion of HOP in Safety Management System components.

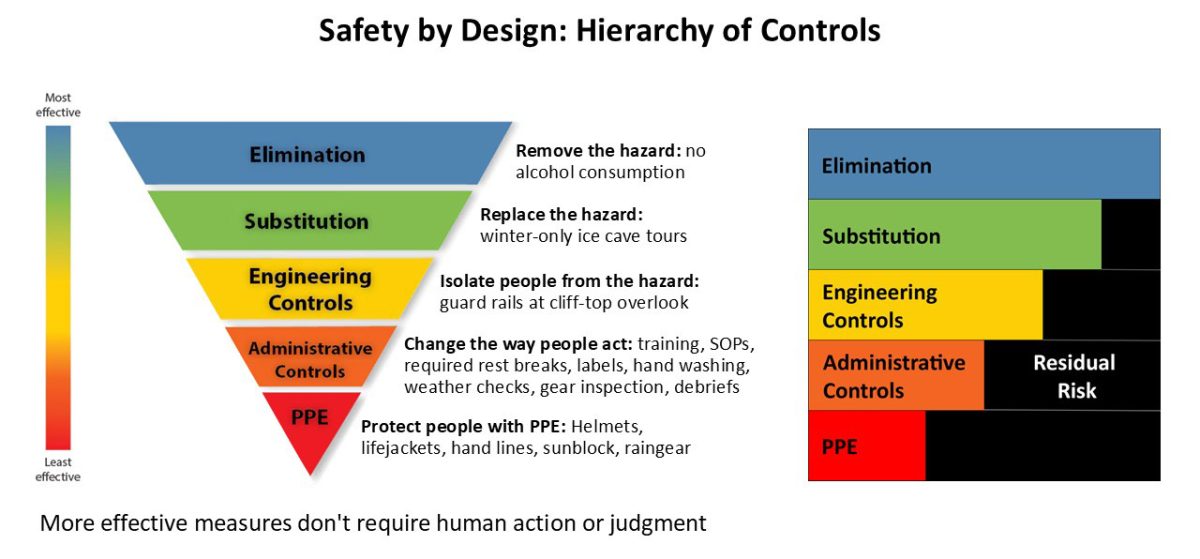

Safety by Design: Hierarchy of Controls

The Hierarchy of Controls approach to safety indicates that the most effective method of controlling a hazard (something that gives rise to a risk) is to eliminate the risk by removing it from the area.

Somewhat less effective is substituting the hazard for something else, with something less hazardous.

Engineering controls, such as guard rails, are even less effective.

Administrative controls—such as training, SOPs, required rest breaks, warning labels, handwashing, weather checks, gear inspection, and debriefs—are even less effective than engineering controls.

That’s because the most effective measures don’t require human action or judgment—such as conducting a safety check properly.

The least effective control is personal protective equipment (PPE), such as helmets and lifejackets.

This is elegantly illustrated in Aotearoa’s Safety Audit Standard for adventure activities, which states:

The operator must eliminate serious risks arising from their activities, so far as is reasonably practicable.

When it is not reasonably practicable to eliminate serious risks, the operator must minimize the serious risks arising from their activities.

In minimizing risks, the operator must (if reasonably practicable) take one or more of the following actions that is most appropriate for the risk:

- substituting the hazard giving rise to the risk with something that gives rise to a lesser risk

- isolating the hazard giving rise to the risk to prevent anyone coming into contact with it

- implementing engineering controls

The operator must manage the remaining risk arising from their activities, by using the administrative controls and/or personal protective equipment that are most appropriate for the risk.

It’s a good idea for adventure safety regulations to require use of the hierarchy of controls.

Safety Culture

We can understand culture to be the beliefs and values that a person holds, which lead to certain behaviors.

We can understand safety culture to be beliefs and values regarding safety—such as the extent to which safety is prioritized over other, legitimate, competing business objectives, such as financial performance and customer satisfaction.

The nature of an organization’s safety culture can have a significant influence on safety outcomes.

A vivid example is the Titan submersible incident, where investigators found a “toxic safety culture” to have contributed to the deaths of passengers on an underwater adventure tourism excursion.

But regulating beliefs and values directly is not possible, or fraught at best.

However, it can be practicable to regulate behaviors—including those that spring from safety-related beliefs and values.

For example, adventure safety regulations can require top leadership to verifiably:

- Understand activities

- Understand risks arising from activities

- Ensure appropriate resources available

- Ensure appropriate resources used

Those interested in high-quality safety management systems can pay attention to human factors in incident causation, the research around judgment and decision-making, principles of Human and Organizational Performance, the use of the Hierarchy of Controls, and techniques for supporting a positive workplace safety culture.

By doing so, the most effective criteria for what should be included in a Safety Management System can be developed, and regulations can promote adventure activity operators understanding and meeting those criteria.

Which Outdoor Sectors To Regulate?

Each jurisdiction seeking to introduce suitable adventure safety regulation may have a different answer to this question.

It’s common, however, for high-risk adventure activities (such as mountaineering, rock climbing, caving and whitewater boating) to be regulated. Lower-risk outdoor activities, such as nature walks or forest bathing, don’t typically fall under an “adventure activity” requiring regulation.

Adventure activities conducted by public schools, voluntary organizations (like clubs), and government and military groups are often exempted from regulation.

(In many cases, school-based outdoor education activities would benefit from regulation, but political factors lead to regulatory loopholes for schools.)

Some technical activities may not fall under adventure activity regulations, if they are suitably regulated elsewhere. For example, paragliding is often regulated by a nation’s civil aviation agency, and ocean-going activities such as sailing are often regulated by a maritime authority such as a shipping inspectorate or Coast Guard.

Components of Regulation

A comprehensive regulatory system for adventure activities can include five components:

- Authorizing law

- Adventure safety regulations

- Standards, with third-party audit

- Approved Codes of Practice

- Private sector collaboration & support

Authorizing law

A government must have the authority to regulate adventure activities.

In many cases, this authority is granted in the jurisdiction’s existing health and safety act.

In settings where this is not the case, a separate law (act) authorizing the government to regulate adventure activities may be required.

Adventure safety regulations

Adventure safety regulations commonly perform several functions. These include:

- Define scope & terms of the regulation

- Establish which agency will regulate adventure activities (usually the jurisdiction’s health and safety regulatory agency)

- Address safety standards, by describing the specific criteria to be met in order to comply with the regulations (see ‘Standards, with third-party audit’ section below)

- Establish business processes for application, registration or licensure, and conformance audits

- Establish processes for revocation, suspension, amendment, appeal, and renewal of registration/licensure

- Establish an approved operator registry—that is, an official list of which businesses have met the regulations and are government-approved to provide adventure activities

- Establish timeframes, such has how long the registration or licensure period lasts

- Establish non-compliance penalties, such as fines for conducting adventure activities without approval

Standards, with third-party audit

These are the specific criteria which an adventure organization should meet. The auditor will use document review, interviews and a site visit to determine whether or not the prospective adventure activity provider meets the criteria.

Criteria will vary depending on the circumstances. Country-specific examples are indicated above, and often include subjects such as:

- Safety Management System (SMS)

- Top leader commitment

- Safety objectives

- Risk communication

- Staff training

- Risk assessment, management

- Drug & alcohol risks

- Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs)

- Staff competence

- Dynamic risk management

- Participant supervision

- Clothing & equipment

- Field communications

- Emergency response plan

- Incident reporting & review

- Suitable documentation

- Continual improvement process

Approved Codes of Practice

An “Approved Code of Practice” (ACOP) is a document that gives a detailed description of how certain activities (such as whitewater rafting or zipline operations) are to be conducted, and which has been formally approved by a relevant government agency.

Conformance to what’s described in an ACOP is typically voluntary.

However, in some jurisdictions, such as in the UK, if an organization has a safety incident, but they have followed all the requirements in the applicable ACOP, they may be protected from claims of negligence, with respect to the activities covered in the ACOP. This can be a valuable legal protection for adventure operators.

ACOPs are normally written in collaboration between adventure industry professionals (who know the activities well) and government regulators (who understand principles of ACOP design).

ACOPs are typically highly detailed, describing specifics of participant-to-staff ratios, specific qualifications/certifications to be held by activity leaders, specific equipment to be on hand, and so on.

This is in contrast to regulatory language, which normally uses broader terms such as requiring “a sufficient number of competent staff” and “sufficient quantities of necessary equipment.”

Adventure industry associations often take the lead in coordinating the development and publication of Approved Codes of Practice, in coordination with health and safety regulators.

If government regulators are uninterested in engaging in the creation of ACOPs, the private sector can proceed with the development of Codes of Practice (or documents of the same general purpose but of a different name, such as Good Practice Guideline, Activity Safety Guideline, Adventure Activity Standard, or the like).

Private sector collaboration & support

The best regulatory structures are developed with a close and mutually supportive relationship between the private sector and government regulators.

This is sometimes easier said than done. But high-functioning governments and well-developed adventure industry associations regularly do this around the world.

Regulators should do more than just make rules for businesses to follow. In a positive regulatory context, government bodies can perform some or all of the following functions:

- Develop laws, regulations, codes of practice in collaboration with:

- Operators

- Governing bodies

- Industry associations

- Collaborate on development of:

- Training & qualifications (certification) scheme for adventure activity leaders

- Organizational accreditation

- Activity standards

- Good Practice Guides (GPGs)

- Provide funding and logistical support to private sector to support this work

Regulatory Development Good Practice

Good practice in development and implementation of regulation includes the following.

Provide sufficient time for operators to prepare, before regulations come into force. This will depend on the circumstances, but may be between one to five years, for any given regulation.

Government should provide funding to industry to develop templates, standards, good practice guides, training schemes, and other assets so that the private sector is well-prepared to meet regulatory requirements when they come into force. This can apply to the adventure sector in both low-income and high-income settings.

Adopt suitable content of existing standards, such as EN 15567-1 and EN 15567-2, IFMGA, UIMLA, and Vinnureglur í óbyggðum from Embætti landlæknis. In some cases, a global standard (such as the mountaineering content from IFMGA) or regional standard (such as a European Standard or EN) can be adopted with no change. In other cases, changes to a standard may be necessary for it to fit appropriately into local circumstances.

Many models exist; use one well-suited for local conditions. Adventure regulatory structures that work well in one country may not be suitable in another.

Pay as much attention to enforcement as to regulatory development. Once a regulation has been written, there is much more to do. This includes educating subjects of regulation and developing enforcement resources such as trained personnel. And, importantly, robust and ethical enforcement must occur for even the most well-written regulation to be effective. Good enforcement takes time, money and political will, on both the part of the regulators—and often the regulated.

Government regulators may consider paying for consultants or navigators to support operators in preparing for regulations. This was useful in New Zealand when the adventure activities regulations were passed, with a 12-month period until they took effect. It was important for the government to organize, pay for and send experienced consultants to work directly with smaller adventure operators to help them change their business processes to meet the new requirements. Without this support, many operators may have struggled to meet the requirements and might have shut down, hurting the very industry the regulations were designed to support.

How Do Adventure Professionals View Adventure Safety Regulation?

Viristar’s research indicates that most adventure providers want:

- Clarity on what safety measures are considered to be good practice, and should be implemented to meet a high standard of quality

- A fair business environment. This means an industry where running unsafe operations—which hurt everyone’s reputation and business prospects, when a critical incident occurs—is not allowed. This also means a “level playing field” where operators are not permitted to fail to take reasonable safety precautions in an effort to save money and offer cheaper rates than their competitors.

- Avoidance of bad regulation. This is a significant fear—in some situations, unwarranted, and in other settings, completely understandable. Creating good regulation is really hard. Fairly enforcing it is an additional challenge for regulators. Adventure safety regulation only works well when the regulations are thoughtfully developed in close collaboration with the private sector, and there is robust and ethical enforcement of its requirements.

Adventure operators in New Zealand, Switzerland and the UK generally have come to welcome adventure safety regulation, for the predictability it brings to the business environment, for the end to sudden closures of operating areas following a safety incident by another provider, and for how good regulation improves the effectiveness and reputation of all providers and the entire adventure industry.

However, particularly in countries with a strong anti-regulatory culture, some adventure operators will advocate against regulation.

When is the Right Time to Pursue Adventure Safety Regulation?

Conditions when pursuing regulation is likely to be advantageous include the following:

- Government policy is relatively stable, even when a new ruling party comes into power

- Government regulators and private sector players both have the capacity for constructive government-industry collaboration

- Government regulators have the capacity (staff, time, money, anti-corruption measures) for effective enforcement

- Government regulators have the capacity for continual improvement of the regulatory system. This also takes time, money and political will.

- Industry associations are well-organized and capable of bringing adventure operators together to advocate with one voice and create training programs, codes of practice and other assets

- The political environment supports thoughtful governance. An example is a setting in which government leaders work to advance the well-being of those in their jurisdiction, rather than focus on retaining power.

- Government and industry have adequate staff time, money and political will. In low- and middle-income countries and territories, aid from international development agencies has been important for providing the funding, expert personnel, and other resources necessary for developing the adventure sector through regulatory and other means.

Conclusion

The tragic icefall incident on Breiðamerkurjökull in Vatnajökull National Park is a great loss to the loved ones of the tourist who was killed in the ice wall collapse.

The incident is a catalyst, however, for efforts to help prevent future incidents from occurring.

Overall, Iceland has a well-deserved reputation for good safety outcomes in its adventure activities, held in some of the most spectacular and scenic outdoor settings in the world.

Regulators and the adventure travel sector have recognized, however, the opportunity to improve adventure safety through regulation.

Good adventure safety regulation for Iceland should come with comprehensive standards, conformance to which should be verified with an third-party audit by a qualified organization.

Safety requirements should be comprehensive and systems-informed, and not focus excessively on training and decisions of on-the-ground activity leaders.

Regulation should come with time and funding to support sectoral development. Iceland has a mature and well-developed adventure sector with robust industry bodies (such as Félag Fjallaleiðsögumanna á Íslandi, the Association of Icelandic Mountain Guides, and Samtök ferðaþjónustunnar, the Icelandic Travel Industry Association. Nonetheless, government investment in helping the industry create the structures to enable operators to meet effective safety regulations is an important factor in helping make any new regulations be implemented successfully.

Well-developed adventure safety regulation, and robust, fair enforcement of regulatory requirements, can have a powerful influence in bringing the outdoor adventure sector in Iceland to new heights of quality and effectiveness, and further improve Iceland’s reputation as a globally leading destination for those seeking a world-class adventure travel destination.