Lessons for Risk Management in Outdoor, Experiential, Wilderness, Travel and Adventure Programs

How can incidents be prevented? The answer is more complicated than one might think. Responses to this question have evolved over time—and will continue to evolve. Let’s take a brief look at the evolution of thinking about safety and risk management over time.

Like any field of human inquiry, thinkers have built on the intellectual work of others to advance the field, in our case coming to a closer and closer understanding of how accidents occur, and the corollary, how those accidents might be prevented.

We don’t have completely comprehensive answers for those questions at this time—despite our best efforts, planes still fall from the sky, and kids still twist their ankles on the hiking trail—but our thought process is advancing all the time.

Patrick Waterson and others elucidated a history of safety thinking in Defining the Methodological Challenges and Opportunities for an Effective Science of Sociotechnical Systems and Safety (Waterson et al., Ergonomics, 2015, Vol. 58, No. 4), and their thought leadership on this topic, which has been adapted for use in this writing, is gratefully acknowledged.

The ideas on safety thinking here are applicable to many industries and fields—from aviation to health care. They can equally apply to wilderness risk management, outdoor safety at camps and outdoor education centers, and safety management with travel-based, adventure and experiential programs.

I. Age of Technology: Humans As Cogs In A Machine

As a generalization, in the 1800’s, up to the mid-20th century, a mechanistic view of safety management prevailed. People like factory workers were seen as a component of industrial technology.

Here, the domino model of accident causation was prominent—one thing failed, which caused another thing to fail, which caused a third failure, and then the incident. This linear model held that there was a single root cause to incidents, which if eliminated, could prevent accidents from occurring.

II. Age of Human Factors: Humans As Hazards to Be Controlled

In the 1970’s, a common approach to safety was the idea of controlling human behavior through rule books and policy registers, leading to exhaustive manuals detailing extensive rules that must be followed.

However, managers soon learned that—surprise!—people don’t always follow the rules.

III. Age of Safety Management: Rise of Integrated Safety Culture

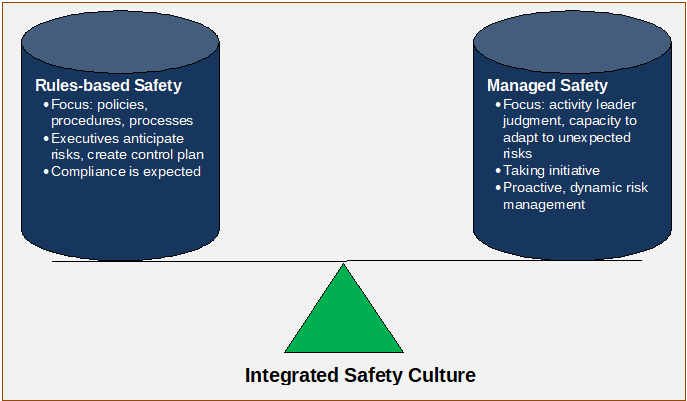

And rules can’t cover all possible situations, so there are times where it’s important to allow people to use their good judgement, rather than follow rigid rules. This was the birth of “integrated safety culture,” which sought to balance the right amount of rules with giving permission for people to make their own decisions.

Using judgement was seen as particularly important in places where the environment might change quickly, and the consequences of mistakes could be grave—piloting an airplane, for example, or in our context, traveling in avalanche terrain.

IV. Age of Systems Thinking: Rise of Application of Complex Socio-Technical Systems Theory

Finally, in more or less the 1990’s, safety thinkers continued to build on the work of those who had come before, and brought the idea of complex systems theory to risk management.

Here we understand environments such as airplane travel or an outdoor program as a complex sociotechnical system. We recognize that in the complex system of an outdoor program, there are many variables at play, and we may not understand or control all of them, or be able to anticipate where the next system component failure may occur.

One of the tools we use to manage risks in these complex systems is engineering in resiliency to the system—for example, only allowing a whitewater paddling instructor to lead trips on water one difficulty level lower than what they’re able to paddle, for example a class IV paddler can only lead trips on class III water. So, if there is an emergency, the leader has a margin of comfort and capacity to help successfully manage the incident.

This is a brief introduction to a complex topic. When well-educated risk managers attempt to prevent incidents from occurring, they bring with them lessons from centuries of thinking and learning about why incidents occur—and how we can stop them from happening in the first place.

Interested in learning more? This outdoor safety topic and many others are covered extensively in Viristar’s Risk Management for Outdoor Programs 40-hour online training course. For more information and a course schedule, click here.