You’re driving back from the trailhead after a fantastic—but exhausting—week on the trail with your group. Heading back to your basecamp down the narrow windy mountain road, dirty but happy, you and your group are looking forward to hot showers and the opportunity to share stories of your wilderness adventures. It’s late at night—your group took longer than planned on the final hike out—but you’ll be home soon.

Crash.

You got into a motor vehicle accident. Thankfully, nobody is injured. There’s just a major dent in the front bumper—and in your pride.

You get back to your basecamp, and next morning explain the accident to the Director. To your shock and surprise, they’re unsympathetic: You had one job! Bring your group back safe from the wilderness! This was a preventable accident—and it’s your fault!

And just like that, you lose your job.

You were the one who ran the vehicle off the road. It was late, you were sleepy, you hadn’t driven the road before, and you lost your concentration—just for a moment. Maybe, just maybe, you were speeding, a tiny bit. So, it really is your fault—right?

Not so fast.

Who is To Blame When an Incident Occurs?

The best thinking about how accidents happen has been changing. Although it’s tempting to blame the person closest to the incident—the belayer who let the climbing rope slip, the inattentive driver—it’s now more clear than ever that reflexively putting 100 percent responsibility on the person most directly involved in the accident is not right.

Sometimes, when a person intentionally causes harm, the blame falls on them, and discipline is justified. But in most cases, if you want to really understand why the accident occurred, and what changes should be made to prevent future incidents from occurring, you have to look at all the factors involved in the entire complex system that surrounds the incident.

This is systems theory, applied to risk management.

Systems Thinking in Incident Causation

What causes a motor vehicle accident?

If we dig into a situation where an outdoor leader transporting a van full of program participants has a motor vehicle accident, possible causes may include, among others:

- Insufficient driver training

- Driver was asked to drive late at night in diminished conditions

- Unwritten expectation to exceed speed limit

- Unwritten expectation to talk on phone with supervisor & staff while driving

- Roadway not properly maintained and signed

For example, fully loaded vans handle differently from the passenger cars with which many drivers are most familiar, and the outdoor program has a responsibility to train their drivers in these new handling characteristics. And special skills like recovering from driving on a soft shoulder back onto the pavement require additional training.

In the story above, the driver appeared to be expected by their employer to drive late at night on an unfamiliar road. The road is narrow and winding, and it’s dark. These conditions increase risk, and the program has a responsibility to proactively minimize these risks through good program design.

Okay, you were speeding, a few kilometers over the speed limit. But the upper managers at the program regularly speed—you’ve driven with your boss while they were exceeding the speed limit. And you were told to get back asap, so participants would be ready for the next day’s activities.

If you’re expected to take calls while on the road by your employer, that’s another risk.

And if the road is damaged or poorly maintained, that can lead to accidents.

Any of these may be contributing factors. And none of them are wholly the direct responsibility of the driver.

An incident analysis that takes into account these factors—that looks at the entire complex system that surrounds the incident—is better equipped to understand why the incident occurred, and what can be done to prevent a recurrence.

Systems Thinking Application: Incident Reporting

Applying a systems-informed lens to managing risks can occur in many places—in program design, in proactive risk management reviews, in staff training, in human resources systems like quality assurance/discipline procedures, and elsewhere. Let’s focus here on one small element of an outdoor program where systems thinking can be usefully applied to help manage risk: incident reporting.

When an incident occurs—injury, illness, behavioral issue, property damage or otherwise—it’s typical to write an Incident Report documenting what happened. The Incident Report covers the who, what, where, when, and how of the mishap—and also the why.

This is where a systems thinking perspective is especially useful.

A traditional incident report may ask, “Why did the incident occur?”

And the response might be: the belayer let the rope go, and the climber fell on their ankle.

Or, the driver, who was speeding, lost focus, and ran off the road and dented the vehicle’s front bumper by hitting a tree.

But we know this isn’t the whole story, and misses opportunities to address the full set of causes that led to the incident.

The UPLOADS Project

Some of the world’s best thinking on systems-informed outdoor safety comes from Australia, including from those at the Centre for Human Factors and Sociotechnical Systems at the University of the Sunshine Coast in Queensland, founded and led by Professor Paul Salmon.

In 2017, Professor Salmon and his colleagues published a paper on “A new incident reporting and learning system for led outdoor activities,” and the idea was in 2018 expanded into book form, Translating Systems Thinking into Practice: A Guide to Developing Incident Reporting Systems.

The idea was to take the systems-thinking perspective and translate it into an outdoor incident reporting tool that would not just look at the proximate cause of an incident—a careless belayer, an inattentive driver—but the whole set of factors contributing to the mishap.

This led to the creation of the UPLOADS Project, the Understanding and Preventing Led Outdoor Accidents Data System. This is a computerized resource for reporting outdoor incidents, in a systems-informed way, and then learning from the data gathered in order to improve safety for all outdoor programs.

In essence, the app-based incident reporting system asks users to consider contributing factors from multiple sources:

- Governance, education and regulation

- Clients

- Led Outdoor Activity Planning, Supervision and Management

- People directly involved in the incident

- Activity resources and environment

By considering contributing factors from sources such as government, the outdoor industry, regulators, accreditation agencies, program designers, client organizations, and program administrators, much more effective plans for preventing future incidents can be developed.

And if your momentary lapse of attention while driving back from the trailhead late one night leads you to a fender-bender accident, you can rest assured that an organization applying the UPLOADS approach is less likely to blame you, and more likely to look at factors such as travel planning and staff training, in order to prevent the next vehicle accident.

The UPLOADS system, funded in part by the Australian Research Council, is currently only available to Australia-based organizations. However, UPLOADS is an extremely promising development, and a true global role model. Applying the UPLOADS approach to incident reporting can be useful to outdoor programs world-wide.

IncidentAnalytix

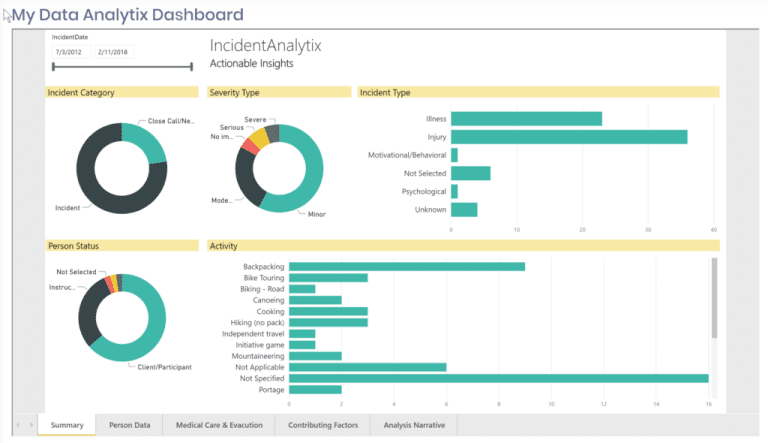

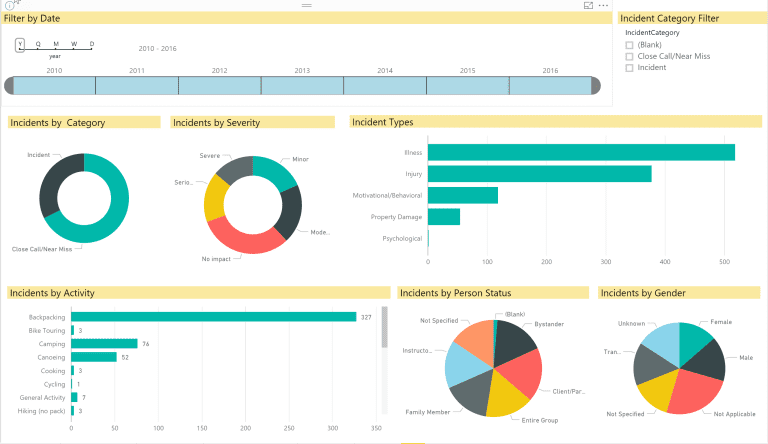

Another systems-based incident reporting technology comes from the USA. IncidentAnalytix is a cloud-based enterprise-level Risk Management Information System that allows for similar inputs to those seen in the UPLOADS model. Developed by Rick Curtis, the founder and CEO of OutdoorEd.com and long-time director of the Outdoor Action Program at Princeton University, IncidentAnalytix offers subscribers a sophisticated database in which to enter outdoor incident data, and from which to draw systems-informed conclustions about incident causation and prevention.

Users can evaluate contributing factors as well other data:

With the capability to generate a wide variety of reports, the IncidentAnalytix solution works best when an organization has a substantial number of incidents—generating insights from a dataset of 1,000 incidents will be more useful than analyzing just three. But IncidentAnalytix, available for a fee to outdoor programs world-wide, is, like UPLOADS, a powerful technology for understanding incidents informed by complex socio-technical systems theory, and usefully generating actionable data to help identify and mitigate root causes of incidents.

Systems and You

The UPLOADS Project technology and IncidentAnalytix information system are both leaders in helping organizations understand the full set of influences that may lead to loss during outdoor programs. One may be a good fit for your organization.

And even if not, any organization can evaluate their incidents from a systems perspective to most effectively prevent future loss. How can we design our program to reduce risks? How can we improve our safety culture? Can we strengthen the outdoor sector by supporting accreditation, governing bodies, or sensible regulation? How do we incorporate elements of just culture into our incident response? A systems-informed approach to reporting incidents and analyzing incident data can help outdoor programs answer these questions and more.

And ultimately, by doing so, an outdoor program that uses a systems-informed approach to incident reporting and analysis improves outcomes for their participants and their organization, as well as the outdoor profession generally and society overall.

Learning More

Systems theory is complex, and its application to outdoor programming is still relatively new. Viristar offers two resources that can help interested individuals learn more:

- The textbook Risk Management for Outdoor Programs: A Guide to Safety in Outdoor Education, Recreation and Adventure walks readers through a systems-based approach to understanding outdoor safety. This acclaimed 218-page textbook is a leading resource for outdoor professionals who seek the most current understanding of best practices in outdoor risk management. The text is available as paperback and e-book.

- Participants in Viristar’s Risk Management for Outdoor Programs 40-hour online training review systems thinking and incident reporting systems. They analyze their own organization’s risk management systems, and develop a Strategic Action Plan that can help them prioritize improvements to their outdoor program’s safety infrastructure—including incident reporting. This comprehensive course provides one of the most detailed and effective training experiences in outdoor risk management available anywhere.

No matter your situation—a program manager or a late-night driver—learning about and implementing a systems-informed approach to understanding how incidents occur, and how they can be prevented, can be valuable to you and your outdoor program.