On September 26, 2024, a school group was on an overnight field trip to the Howell Nature Center in Michigan USA, when a tree fell where a student group was learning how to make a fire. A 12-year-old boy was hit on the head by the falling tree. He was transported by helicopter to a medical center, where he was pronounced dead.

The tragic incident raises the question: how best can nature centers manage risks arising out of their outdoor learning activities?

In this article, we’ll address that question, and briefly cover the following subjects:

- Basic concepts in risk management

- Incident prevention models

- The Risk Domains model, including Risk domains and risk management instruments

- Safety by Design

- Standards and Laws

Nature center risks are generally low. Administrators of nature centers and environmental learning centers can reduce risk by taking advantage of the results of safety science research, and using a suitable incident causation model to help understand how incidents occur and how risks can be reduced. Nature center administrators should reasonably ensure their operation complies with legal requirements, and should consider good practice standards for safety in environmental education and outdoor adventure.

Basic Concepts in Risk Management

We can consider “risk” to mean the possibility of undesirable loss. Loss can be in the form of physical illness or injury, psychological harm (such as might come from exclusion, bullying harassment, psychological stress injury following a critical incident, or other causes), property damage, business interruption, reputational harm or other types of loss.

There are many ways to define the term “risk management.” For our purposes here, we can consider “risk management” to mean the intentional, systematic process of reducing risk so far as is reasonably practicable.

Four principal approaches to managing risk are:

- Eliminate. This involves avoiding certain activities, locations, or conditions—for example, not engaging in whitewater boating, where risks may be higher than on flatwater boating experiences.

- Reduce. This involves instituting sound safety practices. For example, a nature center might hire a certified arborist to inspect the tree near its trails, buildings and gathering spots, and remove hazardous trees.

- Transfer. This involves passing risk to insurers, third-party providers, and program participants (both a participating group and the individual participants (or their guardians/parents) of that group. Insurance policies, contractor agreements, and liability releases are among the tools used in this risk transfer.

Accept. Nature center staff, and participants in nature center activities, can accept that some risks are inherent in activities such as hiking, paddling, and environmental learning experiences, and can choose to acknowledge and accept those risks before organizing or participating in those activities.

Models of Incident Causation and Prevention

Contemporary models of incident causation and prevention are based on complex socio-technical systems theory. This systems-informed approach is an evolution from earlier, more simplistic models, that sought to identify a single or small number of “root causes,” or attempted to identify risks one-by-one and treat each risk in isolation.

A risk management model based on systems theory recognizes that complex systems have the following characteristics:

- Difficulty in achieving widely shared recognition that a problem even exists, and agreeing on a shared definition of the problem

- Difficulty identifying all the specific factors that influence the problem

- Limited or no influence or control over some causal elements of the problem

- Uncertainty about the impacts of specific interventions

- Incomplete information about the causes of the problem and the effectiveness of potential solutions

- A constantly shifting landscape where the nature of the problem itself and potential solutions are always changing

Examples of these complex systems include the global climate emergency, issues of inequity and exclusion in society, and organized outdoor activities.

In a complex system, we can recognize that the failure of one or more elements of a safety system is inevitable. How and when this failure will occur, however, is unclear.

To address this uncertainty, nature center administrators can use ‘resilience engineering’ practices to guard against a complex and ever-changing set of risks. These practices, used to manage risks in industries from aviation and healthcare to nuclear power generation and outdoor adventure, include using redundancy and extra capacity to help ensure that when a component of the safety system—such as anticipating severe weather, or following established safety procedures—fails, the consequences are mitigated and a catastrophic outcome is avoided.

There are dozens of theoretical models which attempt to employ systems thinking into the design of approaches to risk management.

AcciMap

One of the most widely used models is the AcciMap model, developed by the Danish professor Jens Rasmussen.

Rasmussen’s model posited that to have optimal safety outcomes, steps must be taken at all levels of the complex socio-technical system surrounding the activity. One way of breaking down this model into different levels of action is as follows:

- Government should pass laws and establish regulations setting safety requirements

- Associations of industry operators should create codes of practice, good practice guidelines, training systems, and accreditation programs for private sector operators

- Organizations providing goods and services should establish safe work policies

- Management of those organizations should develop operating plans that reduce risks

- Staff at the direct-service level (for example, factory line workers, or in the nature center context, environmental educators) should perform work tasks appropriately

- Work tasks should be designed from the beginning to have risk engineered out of the task

Risk Domains

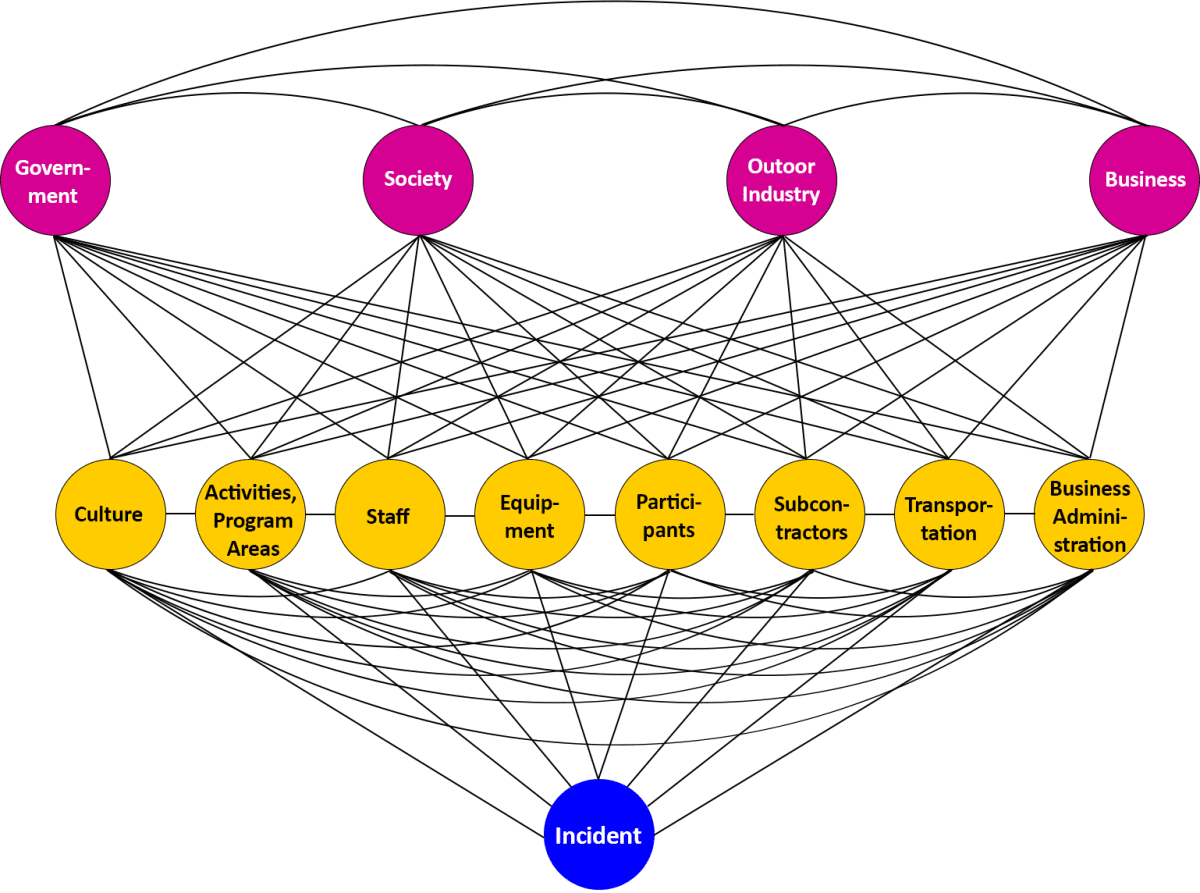

Another systems-informed model of risk management is the Risk Domains model, which was developed specifically for the outdoor and adventure sector.

In this model, eight “direct risk domains” indicate reservoirs where risks directly influencing incident causation lie. These direct risk domains, pictured (in yellow) in the image below, are: organizational culture, activities and program areas, staff, equipment, participants, subcontractors, transportation, and business administration.

The Risk Domains model also includes four “indirect risk domains,” where action can indirectly influence the likelihood or severity of an incident arising from an outdoor, environmental learning or adventure activity. These indirect risk domains, pictured (in fuchsia) in the image below, are: government, society, outdoor industry, and business.

The organization should complete a risk assessment to identify which risks exist in each risk domain for the organization. Organizational leadership should then institute policies, procedures, values and systems to reduce those risks so far as is reasonably practicable.

The Risk Domains model also incorporates 11 “risk management instruments,” or broad-based tools, which can be used to reduce risks in multiple or all direct risk domains.

These risk management instruments are: risk transfer, incident management, incident reporting, incident reviews, risk management committee, medical screening, risk management reviews, media relations, documentation, accreditation, and seeing systems (systems thinking).

Organizational leadership should evaluate, for each risk management instrument, whether the organization should apply that risk management instrument, and if so, how this should be done.

Managing Risks in Risk Domains: Direct Risk Domains

Let’s look at each of eight direct risk domains and four indirect risk domains, one by one, and explore how a nature center might reduce risks found in these risk domains.

Organizational Culture

The risk domain of Organizational Culture has to do with the beliefs and values that individuals, and groups of individuals, hold. Those beliefs and values, which are not always visible, influence behaviors, which normally are visible.

The focus here is on “safety culture”—that is, the beliefs and values around safety, which drive safety-related behaviors.

This can include considering the priority that top leadership at the organization places on safety, relative to how it prioritizes other legitimate and potentially competing aims, such as financial performance, product line expansion, or customer satisfaction.

Organizations may face financial pressures to limit investments in safety, such as developing safety procedures and training staff in them, in order to meet financial targets.

Some persons might see safety actions such as completing checklists to be a burden to be dispensed with as quickly as possible.

Managers might hold a mistaken belief that individual staff should be blamed and punished when they make an honest mistake that leads to an incident, rather than looking at the underlying factors—which might include actions of management—that may have led to the incident. This lack of a Just Culture can be considered an aspect of an organization’s safety culture.

Activities & Program Areas

Managing risks in outdoor learning activities, and the program areas in which they occur, should take place before, during and after those activities are held.

Before an activity, the organization should select program areas with the lowest risk that meet programmatic objectives. For example, if a natural area within walking distance along a trail is just as suitable for a field science exploration as a natural area an hour’s drive away, selecting the closer location can eliminate risks associated with motor vehicle operations.

The organization should conduct an assessment of what risks might arise from a program activity or an area where the activity is to be held. This should be done:

- During the planning stages, prior to the proposed activity being conducted in the proposed area

- Any time conditions may have changed, for example:

- A new participant demographic (for example, older adults, adjudicated youth, pre-schoolers or disabled persons) is considered

- Sufficient time has passed so that risks associated with an activity program area may have changed

- New circumstances, such as a disease outbreak or pandemic, may have emerged

The results of these risk assessments should be documented in standard operating procedures (SOPs). Activity leaders and their supervisors should receive adequate training on those SOPs, and the resources—such as sufficient time, and appropriate equipment—to implement those procedures should be made available.

During an activity, activity leaders should continually scan the environment for hazards and risks. This proactive vigilance is known as “dynamic risk management.” Examples include changes in weather or other environmental conditions, fatigue or distress on the part of participants, the appearance of potentially dangerous persons, emerging equipment problems, and more.

Following an activity, activity leaders and participants should have the opportunity to provide information to management about safety. This can be as informal as a quick observation of the emotional state of young children after a nature-based preschool experience, or can take the form of a feedback form filled out by participants or a detailed safety report completed by activity leaders.

It’s essential that management then receives relevant feedback and systematically and effectively acts upon that information. Reports should not just be filed away, but administrators should have and use a business process to verifiably take action on safety information they receive.

A selection of safety incidents related to program areas and sites used by nature centers and environmental education organizations include:

- On July 10, 1996, a rockslide of some 30,000 cubic meters of rock weighing approximately 90,000 tons occurred near Glacier Point in Yosemite National Park. The impact created an air blast with wind speeds up to 400 kph (280 mph), and uprooted and snapped about 1,000 trees. The Nature Center at Happy Isles was damaged, and a 20-year-old hiker nearby was killed. A cloud of abrasive, pulverized rock covered the area with dust, hampering emergency response and recovery efforts.

- On October 9, 2025 a building fire in Nederland, Colorado destroyed the downtown nature center of the Wild Bear Nature Center, destroying educational materials and leading to the loss of the center’s ambassador animals. (Fundraising for a replacement nature center is underway.)

- The 2018 Woolsey Fire in southern California burned about 100,000 acres of land and forced the indefinite closure of the Santa Monica Mountains Institute, a NatureBridge-operated environmental learning center. The global climate crisis is expected to increase outdoor risk for years to come.

Staff

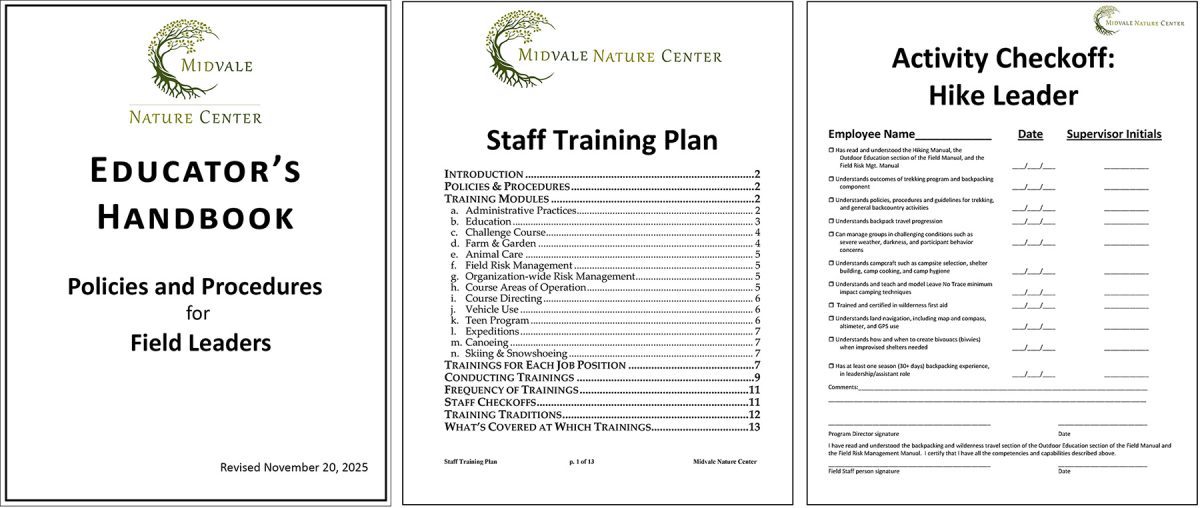

Nature center staff—from educators to administrators—should be competent to perform their work tasks.

This means that personnel should receive adequate training, and verification of successful completion of training activities should be available.

Credentials in some cases are a useful means of demonstrating evidence of training.

This can include, among other examples, certification in first aid, certification as a challenge course practitioner to the standards of ACCT International, or certification as an environmental educator by an NAAEE-accredited training provider.

Administrators of outdoor programs may find it helpful to complete certified training in risk management to help them meet their managerial health and safety duties.

Risk management should be incorporated into the entire human resources management cycle. This includes incorporation safety requirements into position announcements and job descriptions, evaluating past risk management performance during the hiring process, and incorporating safety performance in supervision, performance evaluation, promotion and exit interview processes.

These measures should apply to all organizational personnel, from the CEO to staff leading nature education activities.

Equipment

Equipment, supplies and other physical items—from vehicles, lifejackets and nature art supplies to fences, vessels and buildings—should be managed according to industry standards and, where applicable, original equipment manufacturer recommendations.

This applies to all steps in the equipment life cycle:

- Selection

- Purchase

- Use

- Maintenance

- Repair

- Inspection

- Location and storage

- Retirement

Inventory control measures to ensure that, for example, adequate and unexpired first aid items are available, should be put into place.

Documentation of inspection, maintenance and repair of items where mismanagement could give rise to serious risk should be maintained. (This could apply to items including, but not limited to, vehicles, vessels, emergency response materials, and technical installations such as a climbing wall.)

If a third party provides certain items—such as a rental vehicle or accommodations—those should be inspected and managed appropriately as well.

Staff and participants must have sufficient training to use equipment appropriately. For example, training should be provided for operating vehicles and vessels, using power equipment such as chainsaws, using items such as camp stoves and lanterns with flammable fuel, wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) for fall protection or drowning prevention, and the like.

Incident at Nature Center Challenge Course

On July 29, 2015, at the Ijams Nature Center in Knoxville Tennessee, an 18-year-old guest fell off the nature center’s newly-opened challenge course, which was operated by a third party. The participant’s neck became entangled in the safety lanyards, and he was suspended in the air, “hanging by his throat” until staff could access him and lower him to the ground.

A post-incident analysis report concluded “course is not safe and operable due to increased risk of harm resulting from patron lanyard design, and operational equipment system incompatibility.”

The Tennessee Department of Labor & Workforce Development ordered the adventure course closed, stating “the device in question is unsafe and inoperable.”

The fatal incident preceded a similar tragedy in 2021, where, following the asphyxiation death of a challenge course participant who fell from a course element, the activity leader was sentenced to jail and the company was criminally charged.

Participants

Participant risk management can be divided into safety actions taken before, during and after their participation in nature center activities.

Pre-program

Nature centers and related organizations should have a process of selecting participant groups well-matched to the organization’s competencies. A nature center experienced in providing half-day field trips to primary school students, for example, may need to develop new risk management procedures before it offers an outdoor adventure program for teens.

An outdoor activity center in England that primarily worked with able-bodied participants was found to have failed to complete an adequate risk assessment and management process for working with wheelchair-bound participants, according to a governmental investigation following the drowning of two participants on a boating activity at the center. The investigative report concluded that the risk assessment developed by the activity center—which specialized in water-based activities, and which had a boat specially built to accommodate wheelchair users—“did not identify hazards associated with having wheelchair users on the boat.”

Participants should also go through a medical screening process, where awareness of a prospective participant’s medical circumstances is important in managing risk.

Medical screening helps ensure that the appropriate measures are taken to accommodate a participant’s medical circumstances.

Depending on the nature of the activity, program locations and participant medical circumstances, this can range from simple to very in-depth medical screening processes.

For example, licensing requirements for operating an outdoor nature-based child care program in Washington state USA include detailed requirements regarding managing allergies, continual assessment for illness, individual care plans for children carrying asthma or anaphylaxis medication, immunization tracking, and more.

Medical Screening Case Study: Diabetes on a School Trip

In 2019, 16-year-old Lachlan Cook took part in a trip organized by their school. Lachlan was diabetic, and on the trip he began showing signs of diabetic hyperglycemia—repeated vomiting, thirst, pain, fast breathing, and low energy. The provider’s trip leader, who knew Lachlan was diabetic, lacked the knowledge and training to recognize the problem. Lachlan became nonresponsive and went into cardiac arrest.

An investigation determined that the school’s diabetes management and action plans for Lachlan were not taken on the trip, which delayed diagnosis; the trip provider didn’t provide additional training to the trip leader to assist with their diabetes knowledge, and there appeared to be confusion about who—the provider or the school—was responsible for Lachlan’s medical care, where the provider appeared to assume Lachlan would manage his own condition.

The activity provider pleaded guilty to a health and safety charge and was fined.

The coroner noted that the circumstances leading to Lachlan’s death were “easily avoidable and rectifiable.”

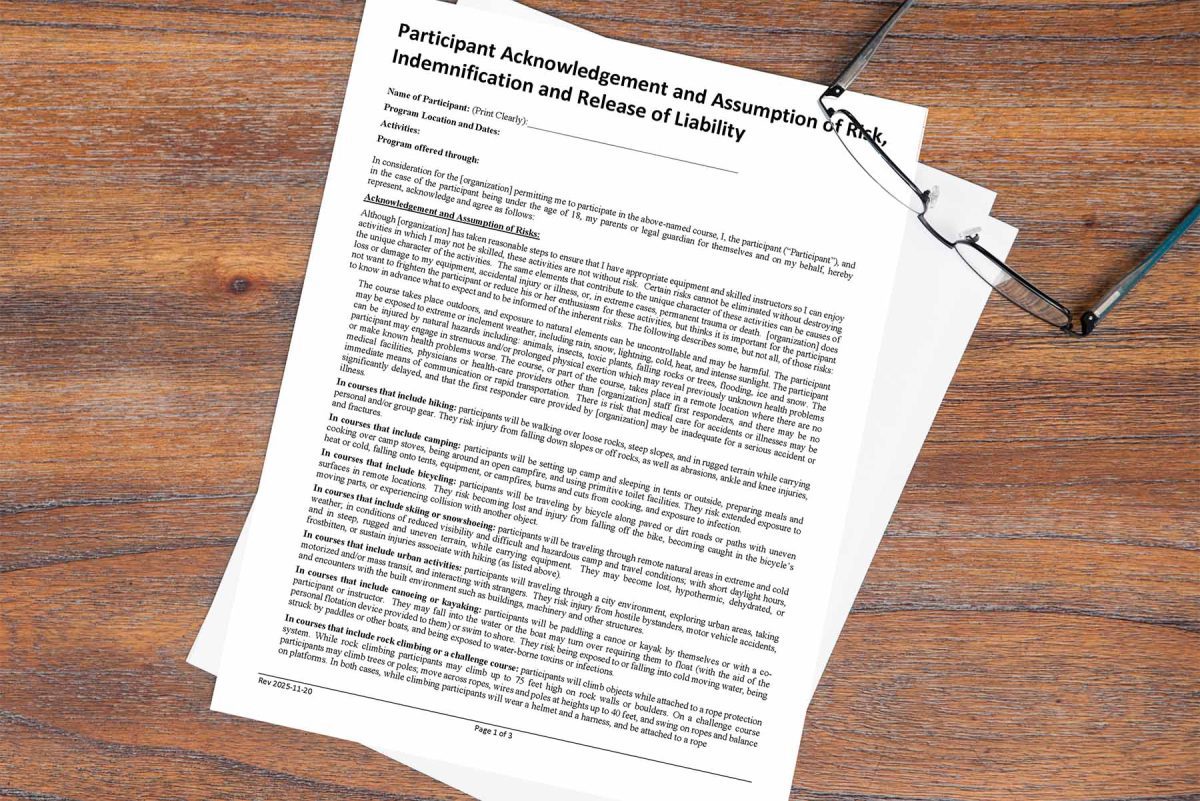

Participants (or their guardian or parent, if the participant is a legal minor, or in some cases the minor participant and the guardian/parent) should sign an acknowledgement and assumption of risk, release of liability and indemnification form, prior to participation in activities. Use of such a form should conform to applicable law, and nature centers should consult with a qualified attorney to understand what this form (sometimes called a “waiver”) should say and how it should be used.

During the Program

Participants should receive training in managing risks arising from the activities in which they engage. For example, individuals going boating should be instructed in water safety procedures, and hikers should be provided information regarding how to avoid getting lost and what to do if they become separated from the group.

Participants should also be appropriately supervised by activity leaders.

The program should have procedures regarding the ratio of competent activity leaders to participants, and when varying levels of supervision—direct supervision, indirect supervision, or remote supervision—are appropriate.

The program should address how persons (such as parent or teacher chaperones) who do not have professional training in the safe conduct of outdoor activities should be accounted for in supervision of participants.

After the Program

At the end of the program, participants and leaders of participant groups should have the opportunity to share their assessment of safety management with the nature center’s management.

This might include opportunities for participants to give feedback to nature center staff directly. It might also include formalized opportunities (such as surveys) for the group leader—if participants came to the nature center as part of an organized group—to provide an evaluation of safety measures to the nature center.

When participants are minors, requesting feedback from guardians or parents can also be useful.

Nature center administrators should have a business process for receiving that feedback and verifiably acting upon any concerns raised.

Providers (Contractors)

Nature centers that use third-party providers to supply outdoor or adventure activities with serious risk, or ancillary services such as food service, transportation, or accommodation, should take reasonable steps to ensure that the contractor’s management of risks is suitable.

This may involve requesting written information from the prospective provider on topics such as:

- Permits and certificates

- Prior experience

- Safety record

- Results of previous safety reviews

- Equipment management practices

- Qualifications of contractor’s personnel

- Transportation risk management procedures

- Risk management measures used by supplier’s sub-contractors

- Evidence of suitable liability insurance coverage

This may also involve an on-site inspection of the potential supplier’s physical facilities (such as buildings, vehicles, vessels, or activity installations like climbing walls).

Nature centers should complete this suitability assessment even for long-standing and well-regarded providers, and the assessment should be repeated periodically.

Transportation

Transportation by motor vehicle or vessel brings with it the potential for major incidents, as often larger groups of persons are traveling, and travel sometimes occurs at high speed where incidents can lead to serious injury.

Nature centers should ensure that individuals who operate vehicles and vessels have an appropriate operator record, hold the appropriate operating license, and successfully pass the nature center’s written and practical vehicle or vessel tests.

Vehicle and vessel operators should be trained in the organization’s vehicle/vessel operations procedures.

Those procedures may include, but are not limited to:

- Drug and alcohol use

- Headlight use

- Speed limits

- Loading and unloading

- Hours of service

- Use of phones and other electronics

- Pre-drive checks

- Use logs

- Operating in adverse conditions

- Backing

- Route selection

- Fueling

- Breakdowns

- Collisions

- Seatbelt use

- Passenger management

- Emergency response

The nature center should ensure that vehicles and vessels have the appropriate insurance coverage, and the inspections, maintenance and repairs are conducted to original equipment manufacturer recommendations or industry good practice standards.

Business Administration

The risk domain of “business administration” refers to risks arising from business operations activities, rather than risks associated with outdoor, nature-based or adventure activities.

For example, office buildings and other structures should meet building codes for fire safety and other matters.

Promotional materials should avoid claiming that outdoor activities are “safe,” as—depending on how the word “safe” is interpreted—that might imply to some people that those activities are completely without risk, which can lead to unwanted liability on the part of the nature center should a mishap occur.

Human resources management procedures to address harassment, bullying, assault, unlawful discrimination, and other misconduct should be put into place.

For nature centers providing activities with vulnerable populations such as minor children, older persons, or those with disabilities, a safeguarding or protection policy should be in place. For example, for nature centers that offer overnight experiences for children, a robust child protection (safeguarding) process should be implemented.

The nature center should take reasonable steps to guard against theft of confidential information such as medical history, credit card numbers, or other Personally Identifying Information and Protected Health Information.

Steps to help prevent fraud and theft, such as the use of dual financial controls and an independent financial audit, should be in place.

Nature center administrators or governance personnel should think through strategic risks that over the years or decades could degrade a nature center’s ability to sustainably operate its programs. These strategic risks include geopolitical concerns (particularly for programs operating in politically unstable parts of the world) and climate change.

Managing Risks in Risk Domains: Indirect Risk Domains

Risk domains where risks which may indirectly influence nature center safety outcomes may be found include the following four indirect risk domains:

- Government

- Society

- Outdoor industry

- Business

Government

Government action can have a substantial influence on management of risks at nature centers.

Law and Regulation

Governments can pass and enforce health and safety law that requires businesses—including nature centers—to take reasonable precautions against reasonably foreseeable harms.

In the USA, the Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) Act of 1970 was enacted to assure safe and healthful working conditions for working individuals.

Individual states also have their own safety and health statutes.

Detailed regulations under the OSH Act provide specific direction for particular topics, such as required hazard protection methods, chemical hazards, and much more.

These laws and regulations are only effective, however, when they are appropriately enforced.

Licensure

In some cases, nature centers must obtain a license prior to engaging in certain regulated activities, such as operating an outdoor nature-based childcare or preschool program.

In the USA, Washington state, in 2019, became the first state in the USA to license outdoor, nature-based preschools.

Colorado followed in 2024 with a law authorizing licenses for outdoor preschools, and Oregon began licensing Outdoor Nature-Based Programs in 2025.

Maryland’s Outdoor, Nature-Based Child Care License Pilot Program is underway.

These licensure systems bring with them both safety requirements as well as the potential for government funding to enable people of different levels of financial capacity to access outdoor nature-based childcare and preschool programs, also sometimes known as “forest school.”

There is an ongoing discussion amongst regulators and providers regarding the burden and effectiveness of safety requirements in these relatively new programs.

Funding

Federal and state funding in the USA helps make it possible for outdoor schools and nature preschools to invest in developing safety procedures and having well-trained staff who can provide programs at nature centers and elsewhere with good risk management.

For example, the Washington state legislature has provided up to some $10 million annually through the Outdoor Learning Grant Program to pay for outdoor school experiences for students at locations such as Waskowitz Outdoor Education Center, Mount Rainier Institute, IslandWood, NatureBridge and North Cascades Institute. (The program is unfunded for the 2025-2027 budget cycle.)

Public Land Use

Permit systems to access and use land managed by government agencies for environmental education programming, and public-private partnerships where privately-operated environmental learning centers are run from inside national parks or other public lands, are examples of how government policy can promote a robust network of nature centers and outdoor education programs operating on public lands, often in spectacularly scenic and awe-inspiring outdoor spaces.

When environmental education programs have access to public land, they may be more likely to be able to achieve economies of scale that allow them to more deeply invest in safety and quality.

Society

Some cultures, such as those in Singapore and South Korea, have a relatively low social tolerance for risk, including risks arising from outdoor activities.

Parents may be reluctant to allow their children to participate in nature-based field trips without assurance of excellent safety management, and when an incident does occur, pressure from parents and negative news coverage can lead to decisive action to improve outdoor safety standards.

After four schoolchildren drowned on what was to be a two-hour coastal kayak trip in the UK, relentless pressure from parents led the UK government to pass world-leading adventure safety regulations.

Similarly, an incident at an outdoor adventure center in Singapore led the government to shut down height-based adventure activities for public school students nationwide for two years, and resulted in the development of a new national standard for outdoor adventure education in the island country.

Parents, news media organizations, advocacy groups, and associations supporting nature-based and outdoor activities all have a role in fostering a society that appropriately values safety—in outdoor learning activities and elsewhere.

Business

When businesses—especially large and powerful corporations—exhibit a sense of civic responsibility, this can help support good safety outcomes across all industries.

However, when huge companies lobby to weaken safety regulations and diminish enforcement of existing laws, and seek to push the government to support society’s most privileged over those most vulnerable and in need of support, this can degrade the government’s capacity to support and enforce commonsense safety regulations that apply to all workplaces—from factories to nature centers.

In the USA, observers have noted how the “agenda of civic-mindedness” that characterized corporate boardrooms in the 1950s and 1960s, where many corporate elites thought of themselves as working in the national interest, has been replaced with a view that the interests of shareholders should reign supreme in corporate decision-making, where “chief executives are often more concerned with their share price…than any genteel sense of obligation to a…greater good.”

When corporations feel a responsibility to support an equitable civic society, where government and the private sector work together to support the health, safety and well-being of all, then safety outcomes across all business enterprises may be improved.

Outdoor Industry

Private sector associations involved in the outdoor and environmental sector have a vital role to play in supporting safety in nature center programs.

Industry associations such as the Association of Nature Center Administrators (ANCA) can bring leaders together to collaborate, find support, and share good practices for the nature and environmental learning center profession.

Organizations such as the Association of Zoos and Aquariums have established standards applicable to certain nature center operations

Organizations including the North American Association for Environmental Education (NAAEE) have fostered the development of activity leader certification, such as the Certified Environmental Educator credential, which includes the safety components of NAAEE’s Environmental Educator Knowledge and Skills: Guidelines for Excellence publication.

And a number of organizations offer accreditation programs that help environmental education providers understand and meet safety and quality standards for outdoor, adventure and nature-based experiences.

Associations and related industry bodies also have the opportunity to advocate to government decision-makers for well-developed quality and safety regulation, and the funding to make compliance with those requirements possible.

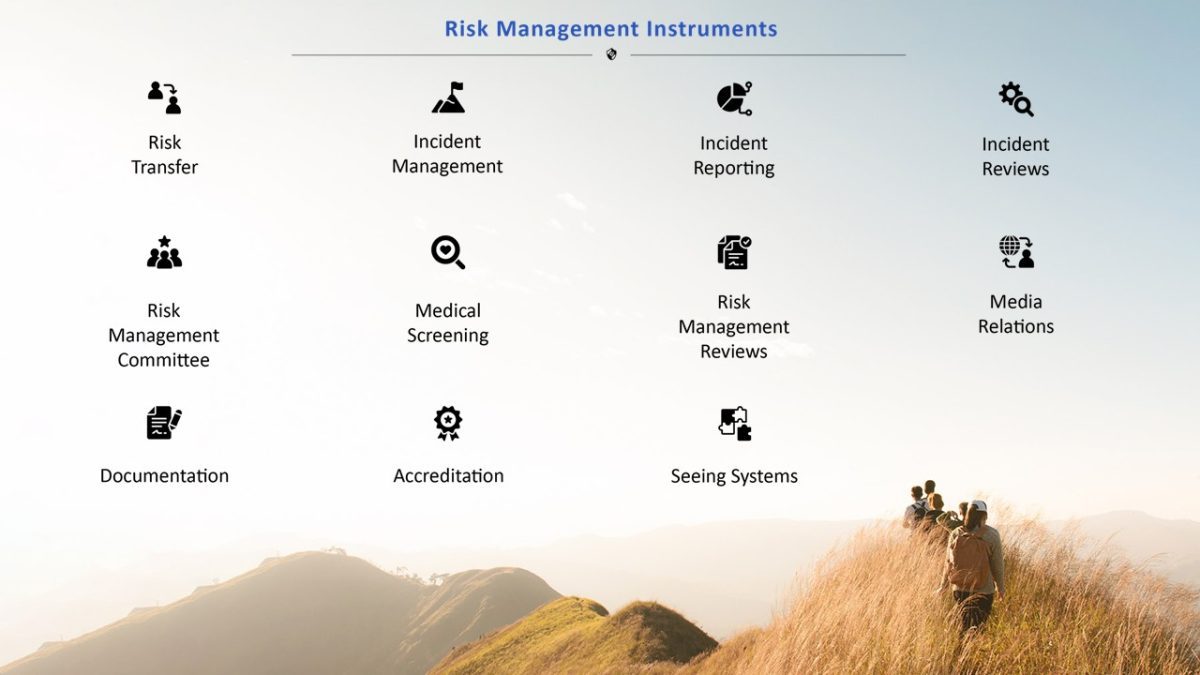

Risk Management Instruments

A nature center can conduct a risk assessment to identify what risks—in the eight “direct risk domains” described above—may arise from its activities and operations, and then institute policies, procedures, values and systems to reduce those risks so far as is reasonably practicable.

Nature centers also have the opportunity to use some or all of the following 11 risk management instruments, or broad safety tools, to reduce risks across multiple or all risk domains:

- Risk Transfer

- Incident Management

- Incident Reporting

- Incident Reviews

- Risk Management Committee

- Medical Screening

- Risk Management Reviews

- Media Relations

- Documentation

- Accreditation

- Seeing Systems

We’ll address each of these risk management tools, one by one.

Risk Transfer

Transfer of risk from a nature center to another party can occur in three ways: through insurance policies, through participants assuming risk, or through the use of contractors.

Insurance

Nature centers should work with a suitable insurance broker to ensure that they have suitable insurance policies with appropriate coverage and with exclusions that are acceptable to the nature center.

Liability insurance is a core policy recommended for every nature center. A huge array of other policies are available, and include property, vehicle, mobile property (inland marine), Directors & Officers, volunteer accident, and many others. A suitable insurance broker can advise as to what coverage may be appropriate for the organization’s unique circumstances.

Participant

Nature centers often work with organized groups, who bring a number of persons to engage in nature center programs.

In establishing contractual arrangements with such groups, the nature center can consider language in which the organization sending participants releases the nature center from liability and indemnifies the nature center. A qualified attorney should be used to establish the appropriate language and terms.

Individual participants (or their guardians/parents, if they are a legal minor, or both the participant and their guardian/parent) should also sign a document which performs the following functions: acknowledgement and assumption of risk, release of liability, and indemnification. A qualified attorney should be used to establish the appropriate language and terms.

Third-party provider

Provision of certain program activities (such as specialized outdoor activities the nature center is not well-suited for providing itself) or ancillary activities such as transportation, food service or overnight accommodation, may be provided by a contractor to the nature center.

This arrangement allows the nature center to provide services well within its core competencies, and to potentially assign risk for other services to another organization.

A suitable and well-developed contract with risk transfer terms should be signed between the two parties. Terms may include evidence of suitable liability insurance cover, listing the nature center as an additional insured, and indemnification of the nature center. A qualified attorney should be used to establish the appropriate language and terms.

Incident Management

Good risk management focuses on preventing incidents from occurring in the first place. But should a mishap transpire, the nature center should be well-prepared to mount an effective response.

A carefully-developed and suitably comprehensive emergency response plan (or situation response plan, crisis management plan, or document of a similar name) can aid in effective incident response.

Some organizations may find it useful to have two separate emergency response plan—one for use in the field, by leaders with a group, and the other for management, for addressing administrative aspects of emergency response.

The content and organization of emergency response plans will vary widely between different nature centers.

The emergency response plan for field personnel may cover topics including, but not limited to:

- Definition of an emergency

- General emergency response steps

- Communications and telecommunications devices

- Incident reporting

- Missing person procedures

- Motor vehicle incidents

- Natural disasters and severe environmental conditions

- Fatality management

- First aid and medical care protocols

- Medical facility information

- Dangerous persons

- Active shooter

- Bomb threat

- Fire

- Responding to psychological emergencies

- Notifying next of kin

- News media relations

- Evacuation

The emergency response plan for administrators may cover topics including, but not limited to:

- Definition of an emergency

- General emergency response steps

- Administrative emergency response procedures

- Emergency notification sequence

- Roles and responsibilities—CEO, Crisis Management Team, etc.

- News media relations

- Call Guide and Emergency Contacts

- Medical facility information

- Supporting mental health after a major incident

The emergency response plan should be repeatedly tested with realistic emergency response drills which involve all levels of the organization—from field personnel and middle management to executive leadership and governance personnel. In once case, the failure to adequately test how to implement and emergency response plan was considered a contributing factor in a drowning incident at an outdoor center.

These simulations should rotate through a variety of emergency scenarios that the nature center might foreseeably encounter.

Emergency response plan documents should be reviewed at least annually, and revised as needed.

Incident Reporting

Nature centers should have a process for documenting and addressing significant incidents.

Each nature center should have an incident report form, and a set of procedures describing how and when it is to be used.

Management must then review the contents of each incident report, and take appropriate steps to adjust operating procedures and practices in light of the data gathered from incident report analysis.

The nature center should seek to foster a culture where reporting of incidents is encouraged, to help the nature center improve its management of risk, and where staff are not inappropriately punished for making honest mistakes.

Incident Review

When a major incident occurs, it’s a good idea for a nature center to conduct a formalized review, or investigation, of the incident.

The purpose is to identify contributing factors to the incident, and to develop recommended actions items to help prevent a recurrence of the same or a similar incident.

A major incident might include, for example, an incident that led to a permanent disability, or significant property damage, or might lead to a claim of legal liability.

When a critical incident—such as a fatality—occurs, a nature center might retain a qualified external investigation team to conduct a formal incident review, perhaps in addition to one conducted internally by nature center staff.

The external review should be conducted by an organization with experience in incident investigations in nature-related fields. Incident reviewers should have expert knowledge of good practice standards in nature center safety, understand the steps in an incident review process, and be able to act in an impartial manner. They should possess the analytical skills to absorb a large amount of novel information in a short time period, synthesize that information into insightful recommendations, and deliver the recommendations orally and in writing in a way that is candid yet diplomatically reflects the sensitive nature of the situation.

Senior management of the nature center should then embark on a systematic process to understand the incident review report recommendations and act on those recommendations.

Risk Management Committee

A Risk Management Committee is a group of persons who seek to support the nature center’s senior leaders in helping ensure that the organization is successfully managing risks arising from the nature center’s operations and programs.

An important characteristic of a Risk Management Committee is that it has members who are external to the nature center—that is, they are not employees of the organization. This helps the committee offer candid views informed by outside perspectives.

Risk Management Committee members might include persons with significant experience in good practice standards in nature center, environmental learning and outdoor education fields. It may also include persons with specific professional expertise—such as an attorney, insurance specialist or physician—who can provide trusted guidance on their areas of expertise.

The Risk Management Committee should meet periodically (for example, monthly or quarterly), and keep minutes of its meetings. Some Risk Management Committees have positions such as Chair and Secretary.

The Risk Management Committee can take a proactive approach to safety, for example supporting safety audits and paying attention to evolving industry standards and new safety measures.

The committee can also act in a responsive role, for example by reviewing incident reports, supporting a formal incident review process, or participating in the preparation of periodic (for instance, quarterly or annual) safety reports.

The role of the Risk Management Committee is different from that of a technical advisor, such as a expert boater or challenge course professional, who can give expert technical guidance on safety standards for specific outdoor activities.

Medical Screening

A nine-year-old recently diagnosed with diabetes wants to participate in an overnight experience at the nature center. They need a shot of insulin in the middle of the night, but they are not able to do it themselves. Your staff do not feel comfortable administering the shot. Due to the short timeframe and scheduling challenges, a family member, nurse or personal care attendant are not available. Should you accept the child onto your overnight program?

You offer a kayaking trip which includes a two-kilometer long water crossing. A person with an uncontrolled seizure disorder wishes to participate. Should you allow them to join the program?

An applicant to your multi-day trip involving mentally and physically challenging travel in a remote wilderness setting recently underwent involuntary hospitalization for self-harm. They attempted suicide with in the last 90 days and have a history of significant self-harm. Should they be admitted onto the trip?

A formal medical screening process can help a nature center answer these and other questions.

Medical screening aims to identify the medical needs of prospective participants—and staff—so that the organization can evaluate their suitability for participation, and make the appropriate preparations to include as many persons as it is reasonably practicable for the nature center to include.

Medical screening for a short program with a generally healthy participant demographic, and with ready access to medical care, in which planned activities are intended to be not physically or psychologically challenging, may look different from medical screening for remote expeditions or extreme activities.

A more basic medical screening might involve a one-page health history form asking questions about topics such as allergies and medications, and with a nurse or physician available on call to answer questions as needed.

A more substantial medical screening process might involve multiple versions of multi-page health history forms, a requirement for a complete physical exam with physician sign-off, supplemental questionnaires (for example, orthopedic, endocrine, psychological, and neurological) for use as needed, a specialist referral process, a specially trained medical screener, ready access to multiple physician specialists, a medical screening manual of 50 or more pages, and more.

Organizations such as the Alliance for Camp Health can provide resources to guide the development of a medical screening system.

A nature center should consult with a licensed physician to determine what kind of medical screening process is suitable for their needs.

Risk Management Review

A Risk Management Review is a periodic, proactive audit of a nature center’s or outdoor education center’s entire safety management system.

Unlike an Incident Review—which is initiated only after a major or critical incident—a Risk Management Review is conducted periodically—for example, every two to four years—as part of a continual improvement process.

The Risk Management Review can be conducted by a team of staff internal to the nature center, or by an external body with specialist expertise in conducting such assessments.

A nature center might choose to alternate between internal and external risk management reviews, to get a balance of perspectives and to meet budgetary considerations.

The American Alliance of Museums can conduct an Organizational Assessment as part of its Museum Assessment Program, which nature centers can use as an external risk management review. The Organizational Assessment, whose availability may be contingent on adequate funding by the federal government’s Institute of Museum and Library Services, is based on the Core Standards for Museums, which have some risk management content.

Media Relations

When a newsworthy incident occurs, reporters may seek information from the nature center where the incident occurred.

Some nature centers, particularly smaller independent organizations, do not have a communications department with career public relations specialists highly experienced in crisis communications.

In cases like this, news media relations training can help nature center administrators be effective when responding to information requests and conducting interviews.

Training can include topics such as how to prepare for and participate in an interview, development of pre-established media messages, restricting access to details such as names of persons involved until next of kin are notified, and how to keep a story short by providing comprehensive and accurate information to media outlets as soon as it is available for release.

Most reporters are sincere professionals who are simply seeking to learn about the who, what, why, when and how of the incident, in order to impartially and accurately support the public’s right to know about newsworthy events.

Some, however, may seek to create an overly sensationalized story, or otherwise cast the nature center in a bad light.

It can be helpful for the nature center to prepare a packet of information in advance that talks about the organization’s programs, its commitment to safety, and its safety record, and to have this readily available (for example on the organization’s website).

It can also be useful for a nature center to prepare a list of local or regional news media outlets, along with their contact information. When a critical incident occurs, the nature center can proactively send information to these media outlets, so they have prompt access to accurate information regarding the incident.

Documentation

Safety documentation serves two general purposes:

- To guide nature center personnel as to what should be done

- To provide information to interested parties regarding what has been done

Documentation giving guidance regarding what should be done can include, but is not limited to, an employee handbook, a handbook containing safety information for educators and other direct-service staff, emergency response plans, standard operating procedures, a risk management plan summarizing the nature center’s approaches to managing safety, manuals or handbooks on topics such as medical screening or vehicle/vessel operations, accreditation standards manuals, and owner’s manuals provided by original equipment manufacturers.

Documents recording what has been done include pre-activity checklists (such as a motor vehicle pre-drive checklist), incident report forms, safety reports, medical report forms (SOAP notes), incident logs or written narratives, training certificates, staff check-off forms (e.g. indicating criteria to lead an activity have been met), inspection reports, risk management review reports, and equipment maintenance or inspection or repair logs, among others.

Nature centers should determine what documentation is needed to provide the organization with adequate information regarding what should be done, and what documentation should be in place to ensure that the nature center can provide convincing evidence that the right things indeed have been done.

In one incident, where an employee died after an incident on the company’s zipline, the health and safety regulator found that there was not documentary evidence that the organization had conducted certain safety activities, and as a consequence concluded that those safety activities had not been conducted.

The regulator cited the organization for a Serious Violation of labor statues dealing with occupational safety and health duties, finding that the company “did not furnish employment and a place of employment which were free from recognized hazards that were causing or likely to cause death or serious harm to employees.”

The company was fined over USD 27,000.

Accreditation

Nature center accreditation involves formal recognition by an impartial, qualified third party that the nature center has been evaluated against recognized and established standards and has demonstrably met those standards.

Accreditation is normally provided by private sector accreditation-granting organizations, as opposed to licensure, which is normally granted by government authorities.

The accreditation process can help a nature center understand what are seen as good practice standards for the sector, and help ensure that the nature center verifiably meets those standards, at least at one point in time.

This can help the nature center advance the safety and quality of its programs, and also bring marketing and reputational benefits.

A number of accreditation options are available to nature centers, environmental learning centers, field science institutes, and similar organizations.

What accreditation options may be suitable for a given nature center depends on factors such as the types of programs it offers, the nature of its facilities and participant demographics, whether or not the nature center is associated with a park and recreation agency, and its level of interest in managing risk arising from adventure activities.

Accreditation options with a risk management component that nature centers might consider include the following:

- American Alliance of Museums accreditation

- Association of Zoos & Aquariums accreditation

- American Camp Association accreditation, and accreditation by other camp associations, for example in Canada and Australia

- National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) Early Learning Program, for outdoor nature-based preschool and similar programs

- ACCT International accreditation, for challenge courses, aerial adventure/trekking park courses, zip lines, and canopy tours

- National Recreation & Park Association accreditation through its Commission for Accreditation of Park and Recreation Agencies (CAPRA), for nature centers connected to park and rec agencies

- Viristar Adventure Safety Accreditation, for nature centers and outdoor programs providing adventure activities

Seeing Systems

“Seeing systems” refers to applying complex socio-technical systems theory to understanding the factors—and the interactions among factors—that lead to an incident’s occurrence, and by correlation, how incidents might be prevented, or their impact mitigated.

Systems theory suggests that major incidents arise from multiple risk factors, which combine in unpredictable ways.

Treating each risk in isolation is less effective than looking at the whole system of risk factors, and how they interact with the mix of people and things that make up a socio-technical system (STS).

In order to have the best probability of preventing incidents, or minimizing their severity, it’s important to build multi-layered, resilient systems with redundancy and extra capacity.

Redundancy can look like having two activity leaders on a remote activity, so that if one is incapacitated, a backup is available. Redundancy can also take the form of multiple means of emergency telecommunications, or contingency plans for severe weather.

Extra capacity might look like a spare paddle on a rafting trip, carrying multiple inhalers so one will still be available to assist in an asthma attack if the other is lost or left at a previous location, or having staff trained to perform adequately in more severe environments than they might normally encounter (such as having a Class IV paddler lead a Class II river trip).

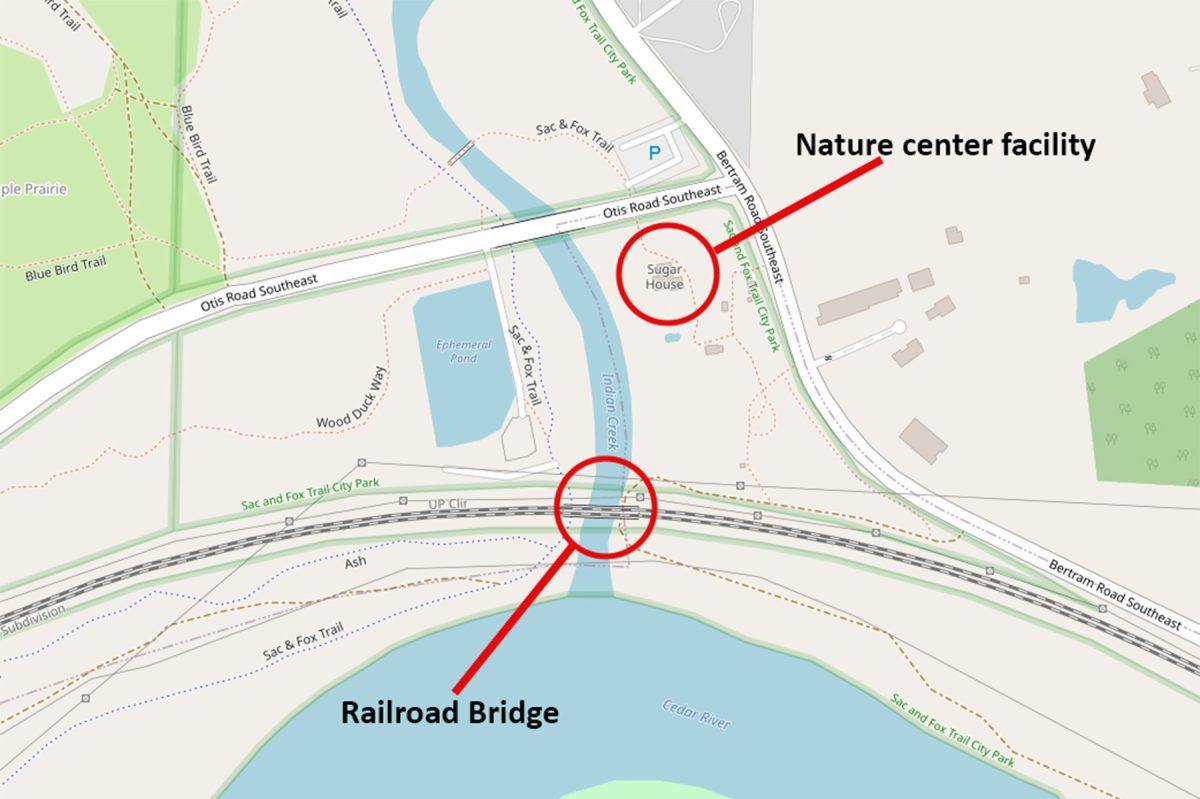

A tragic illustration of the difficult-to-predict nature of major incidents occurred at the Indian Creek Nature Center in Cedar Rapids Iowa in 2002.

An outside group had rented its auditorium for an event—a christening ceremony for a neighbor’s daughter.

After the ceremony, some parents allowed five- and six-year-old children to wander about outside. Some children walked about 800 feet to where a bridge carried train tracks across a creek. Two boys climbed up a steep embankment and onto the bridge, where they were hit by a train. One boy died of his injuries.

The family of the deceased child sued the nature center.

Although the nature center had many important safety measures in place—including capable, experienced leadership, and a history of multiple reviews by external auditors—the incident highlights the complexity and unpredictability of incident causation.

Additional information on managing outdoor risks in the risk domains and using the risk management instruments mentioned above is available in a textbook, Risk Management for Outdoor Programs.

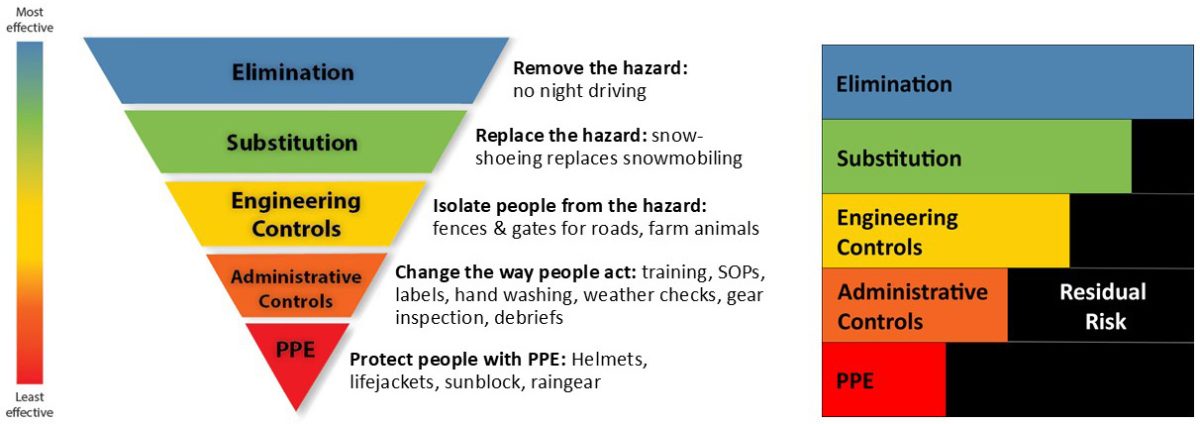

Safety By Design: the Hierarchy of Controls

The concept of “safety by design” refers to designing activities and processes from the very beginning to minimize risk.

A sequence of steps, or “controls,” can be used to reduce risks associated with work tasks and other activities.

Some of these control measures are more effective than others. A hierarchy was developed to rank these control measures from most effective to least effective.

The more effective measures—elimination, substitution, and engineering controls—don’t require human action or judgment.

Less effective measures—administrative controls like safety procedures, training, and equipment inspection—depend on appropriate human action or judgment to be effective.

This helps us understand that a bulk of nature center risk management is managerial in nature—for designing out risks from activities, and maintaining engineering controls to reduce the likelihood of interaction with a hazard.

This understanding can help eliminate the misconception that when an incident occurs, the primary contributing factors are centered around the actions of the activity leader or person closest to the incident.

In some jurisdictions, including Canada and New Zealand, application of the Hierarchy of Controls is required by safety regulation for certain outdoor adventure activities.

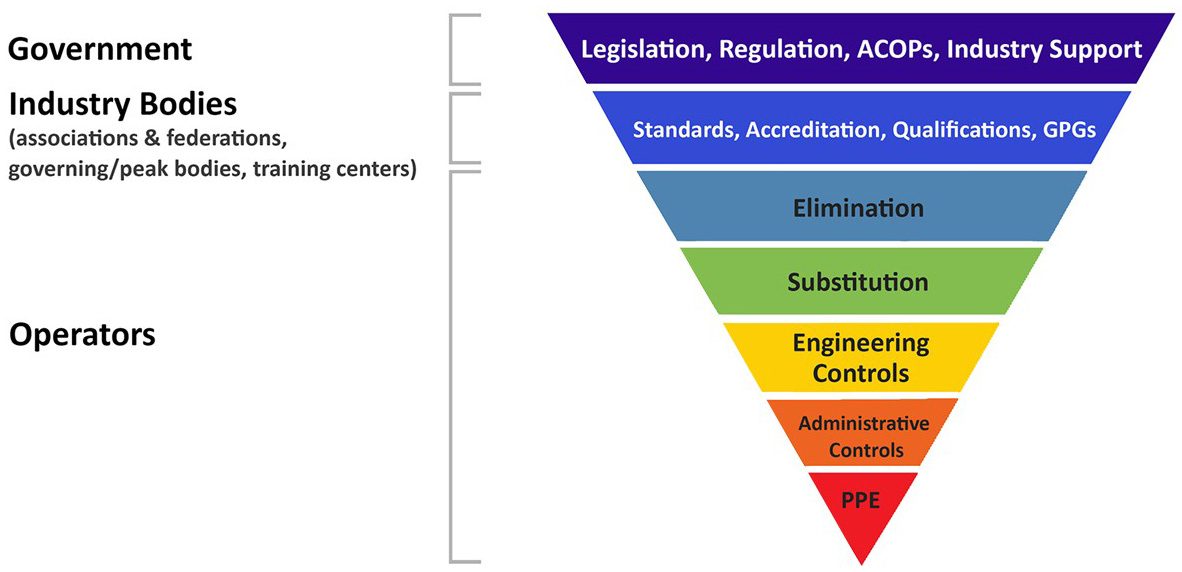

An adaptation of the Hierarchy of Controls to incorporate systems thinking incorporates the role of industry bodies such as associations such as ANCA and NAAEE, as well as government actions, is shown in this “Systems-informed Hierarchy of Controls:”

Here we see how industry bodies that create safety standards and Good Practice Guides, along with government entities which establish safety rules and Approved Codes of Practice, can assist outdoor and nature-based activity providers in supporting good safety outcomes.

For additional information on the hierarchy of controls and outdoor activities, learn more here.

Standards

Well-developed written standards that document good practice in reducing risks of outdoor and nature-based activities are a powerful tool for helping nature centers effectively meet their mission; win enduring support from customers, the general public, and government regulators, and be economically sustainable as a business.

The term “standards” generally refers to criteria for which conformance is voluntary.

A number of organizations which document safety standards applicable to nature centers and allied organizations also incorporate programmatic standards (around natural history interpretation, environmental education pedagogy, or other matters) in their set of standards.

These voluntary good practice standards can complement any safety requirements, for example nature-based early childhood education licensure criteria, that a nature center may be required to meet.

A nature center can acquire a set of standards and seek to meet them on its own. If resources permit, a third-party assessment of conformance to standards, for example by an accrediting body, can be conducted, which may increase the likelihood that the nature center conforms to the full set of standards.

Although most standards are written, nature centers may also be held to unwritten standards, such as the safety measures taken by reasonable and prudent nature centers elsewhere. In the case of a significant incident, failure to show evidence that the nature center meets these unwritten standards can lead to reputational harm or other liability.

The content of written standards documents vary widely in rigor and depth. Some standards are fewer than five pages; others are over 200 pages long. The most well-developed standards tend to be written in precise terms using technical writing style, similar to the particular writing convention used in drafting law and regulation.

Although standards can be immensely valuable in communicating good practice expectations, meeting safety standards does not guarantee that incidents will not occur, and does not eliminate all legal liability on the part of the nature center.

With many sets of standards to choose from, and limited resources for achieving and maintaining standards conformance, nature centers should thoughtfully consider which standards they feel they should adopt for their organizations.

Examples of standards applicable to nature centers and similar organizations, and which contain risk management components, include the following:

- NAAEE Environmental Educator Knowledge and Skills: Guidelines for Excellence

- NAEYC Early Learning Program Quality Assessment and Accreditation: Assessment Items

- ACCT Challenge Courses & Canopy/Zip Line Tours Standards

- Viristar Adventure Safety Accreditation Standards

- AZA Accreditation Standards

- AAM Core Standards for Museums: Facilities & Risk Management

- NRPA CAPRA National Accreditation Standards

- Natural Start Alliance Nature-Based Preschool Professional Practices

- American Camp Association Accreditation Standards

- ISO, NFPA, and ASTM subject-specific standards (such as for snorkeling, fire prevention, and aerial adventure parks)

Laws

Laws, regulations and related requirements vary widely by jurisdiction, and are ever-changing. Organizational leaders should consult a qualified attorney for guidance. The attorney should be familiar with the organization’s activities, and licensed or permitted to practice in the organization’s areas of operation.

The following information is primarily (but not exclusively) focused on the legal context of the USA.

Laws that may apply to nature centers, field studies organizations, and similar organizations can include:

- General occupational health and safety laws in force at the national level and at the sub-national (e.g. state, province) level

- Laws specific to particular topics, such as employment, civil rights, privacy, confidentiality, and the use of liability releases or waivers

- Negligence statutes, where civil or criminal negligence may be found if there was a duty of care, a breach of that duty, damages, and a causal link between the breach and damages

A variety of regulations—which normally sit under an authorizing law, and provide more detail than the broad and sweeping terms of a law—may apply to nature centers. These might include:

- Permitting regulations, such as those requiring a Conditional Use Permit to operate a business or Commercial Use Permit to use certain public lands

- Licensure requirements, which may apply to:

- Summer and year-round camps

- Operation of certain structures such as a climbing wall, zipline or challenge course (often classified as an “amusement ride” or “amusement device”)

- Outdoor nature-based child care/education (sometimes called “forest school,” “nature preschool,” or “forest kindergarten”)

- Zoning requirements and building codes

- Activity-specific regulations—such as US Coast Guard regulations for maritime activities, games of chance (such as fundraising raffles), food safety regulations, and serving alcoholic beverages

- Adventure safety regulations, which are found in countries including New Zealand, the UK, Switzerland, Finland, Oman, the UAE, and some states in India

Another concept in government-issued safety criteria comes in the form of what is called an “Approved Code of Practice.”

A Code of Practice is typically a document that describes detailed procedures for how certain activities—such as hiking or paddlesports—are to be conducted.

An Approved Code of Practice is one that has been approved by a governmental body, typically a healthy and safety regulator, or perhaps a quasi-governmental body such as a standards development organization.

In some jurisdictions, such as the UK, conformance to an Approved Code of Practice (ACOP) can bring important legal protection. If an incident occurs and the organization is investigated for a possible breach of safety law, if the organization has conformed to the ACOP, they are normally found to be doing enough to comply with the law (regarding the subjects on which the ACOP gives advice).

The UK has an ACOP for adventure activities. Singapore recently published an Outdoor Adventure Education Code of Practice. Published Approved Codes of Practice are not commonly found in the outdoor sector in the USA.

Nature centers that provide experiences across political boundaries, such as those that involve international travel, should keep in mind that the application of the rule of law varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. As a consequence, in some nations enforcement of laws is influenced by the political power that involved parties may wield.

Nature center administrators paying attention to safety are often concerned with compliance with the law, and the penalties for noncompliance.

However, it should be noted that laws often set the minimum bar, below which is conduct so poor as to merit civil or criminal penalties. Much of good risk management involves applying good practices that are not required by law, but which can help a nature center provide the best and safest experiences it is reasonably practicable to provide.

As a consequence, an emphasis on merely achieving legal compliance with respect to safety procedures might represent a missed opportunity for a nature to apply good practice standards which can help the organization be the best it can be and achieve excellence in safety and quality.

In some cases, industry associations (such as the American Camp Association and ACCT International) can provide some guidance regarding the presence of legal requirements specific to the activities which the association’s members provide to their customers. However, organizations should consult a qualified attorney for legal advice.

Conclusion

Nature centers provide valuable experiences that bring joy, serenity and life-enriching connections to those who experience nature center programs. Nature centers play a vital role in providing valuable educational experiences, and fostering the ecological sustainability of planet Earth and its lands and waters, upon which all life depends.

Most nature center activities—such as nature arts and crafts, natural history interpretation, exploration of exhibits, presentations, and nature walks—are low-risk.

Some organizational members of the Association of Nature Center Administrators, such as the North Cascades Institute and Canyonlands Field Institute, offer backcountry expeditions and whitewater boating adventures.

Regardless of the level of risk inherent in their program activities, all nature centers and outdoor learning providers can benefit from applying the results of safety science—such as complex sociotechnical systems theory, resilience engineering, and systems-informed theoretical models of incident causation and prevention—to improving safety outcomes at their organization.

Organizations should comply with legal requirements and seek to identify and meet, so far as is practicable, established industry good practice standards.

When an organization does so, they are well-positioned to bring the important and powerful benefits of environmental education and outdoor adventure to more people, which will benefit people and the blue-green earth upon which they live.

Editor’s note: For a copy of the 2025 slide presentation on nature center risk management given to the Association of Nature Center Administrators community, click here.