Introduction

Staff are a critical element in managing risks in outdoor programs. Hiring the right people—and training and supporting them well—is one of the business activities that will have the most impact on an organization, out of any action taken. It’s also challenging to get right.

This article focuses on activity leaders (such as instructors, guides, facilitators, camp counselors, and trip leaders). However, the same principles apply to managers and to anyone within or connected to the organization who has a safety role. This includes, but is not limited to, lead and assistant activity leaders, logistics staff, managers, members of the Risk Management Committee, Board members, interns and fellows, observers, Responsible Persons such as chaperones, and volunteers.

Let’s take a look at the human resources (HR) management function in the outdoor program context. We’ll see that in essence, this process is simply the application of good personnel management principles, applied to outdoor organizations.

The Human Resources Management Process in the Outdoor Program Context

Overview

Steps in the Human Resources Management (HRM) process can be summarized as follows:

I. Establish required staff capacities

II. Hire staff to meet baseline capacities

III. Train staff to meet unmet capacities

IV. Supervise and support staff to maintain capacities

Our discussion of the HRM process will focus on elements specific to outdoor programs. Best practices for interviewing, reference checking, supervision, evaluation, and other general HR practices are available elsewhere and are not extensively covered here.

I. Establish Required Capacities for Staff

Before hiring, it’s necessary to determine what are the desired capacities for staff 1) to be initially hired, and 2) following training, to work with participants in the field. There are multiple models through which to frame these capacities, each with its benefits and drawbacks. We’ll look at four domains of required capacities: knowledge, skills, abilities, and attitudes or values. Descriptions of the latter four terms follow:

Ability: a capacity (to do something), often with an inherited or innate component in addition to a learned component; like dexterity, or ability to distinguish red from green.

In the outdoor context: the ability to lift a canoe out of the water during a canoe-over-canoe rescue.

Skill: a learned competence, developed over time with training and practice. Skill development may also require certain abilities, like able hand-eye coordination in becoming a skilled race-car driver. Skills include time management, surgery, and parenting. (Skill is sometimes used interchangeably with ability, but they are differentiated here.)

In the outdoor context: rescuing an abseiler whose rappel device has jammed; effectively facilitating a group discussion about safety.

Value: how much something is prized/held in regard; preference for action/outcome, view of right and wrong. Attitude: thinking or feeling with respect to favor or disfavor. Although these terms are slightly different, we use them interchangeably here.

In the outdoor context: Taking seriously the safety of outdoor program participants.

The desired capacities in the four domains of knowledge, skills, abilities, and attitudes/values should be clearly documented in published job postings and written job descriptions. They should hold up as adequate under scrutiny. If an employee fails, will your language be seen as contributing to the failure?

In the job descriptions, roles and responsibilities for safety must be clear. Some organizations use a Single Point of Accountability or Person In Charge structure to formalize this responsibility.

Staff Operate Below Limits of Competence. Required capacities for any given position should be such that the individual is operating at a level below their own skill and ability. That is, the activity (such as whitewater boating) at its most difficult should not be a challenge for the activity leader. For instance, a boater who is able to paddle class IV whitewater should only lead trips on class III or lower whitewater. This ensures a margin of safety. Although activity leaders may personally want a challenging high adventure experience, leading a commercial trip with others is not the place for it.

Operating at the limits of one’s competence increases the probability of an incident occurring. It also reduces the cognitive capacities of the individual to respond if something does go wrong: research shows that individuals under stress—or being occupied by multiple tasks, which is often also the case in emergencies—have impaired decision-making and tend to make riskier decisions.

Knowledge, Skills, Abilities and Attitudes for Activity Leaders. Desired capacities for activity leaders can be broken down as described below. Hiring managers should then determine which of these capacities must be met in order for a person to be hired, and which are required (following the completion of staff training) before the activity leader is eligible to lead outdoor programs.

- Technical skills. These apply to the relevant outdoor activities, such as kayaking, climbing, or sailing.

- Interpersonal and leadership skills. These include critically important skills in communication, judgment, and decision-making. Facilitation and group management skills are included here.

- Activity area competence. This refers to the ability to appropriately manage risk in leading activities in the activity areas used the program. In many cases this is developed during the staff training process.

- Emergency management. This includes the capacity to fulfill relevant responsibilities in the organization’s Emergency Management Plan (ERP), following training in the ERP.

- Specialized criteria. Specific qualifications or status here may include a commercial driver’s license, a captain’s license (for sailing programs), ability to pass drug test (legally required for some maritime positions), and the authorization to legally work for the organization.

- Essential functions. These capacities apply to activity leaders as well as participants.

- Attitudes. Conservative safety judgment is an example of a potentially desired value or attitude. This could be addressed in a job description qualification such as ‘proven ability to provide conservative risk management supervision.’

Criminal History. A potential activity leader’s criminal history can provide some, although limited, guidance on the individual’s capacities, particularly when the organization works with minors or vulnerable adults. A criminal history does not necessary preclude an individual from working in an outdoor program. A person with a minor infraction for possession 10 years ago of a drug with low abuse potential, for instance, may in some situations and legal contexts be eligible for hire. However, a criminal conviction for sexual abuse of a minor would generally prohibit a person from working with children.

If a criminal history leads to an employment restriction, the restriction should be relevant to the offence. For instance, an employee convicted of driving under the influence (of alcohol) could be prohibited from driving, but might be eligible to hold other responsibilities.

II. Hire to Meet Baseline Capacities

Once we’ve established the capacities we need in activity leaders, the hiring process can begin. We now seek to hire staff (or engage volunteers) meeting or exceeding the minimum qualifications necessary to be brought on to the organization, knowing that additional training will be necessary before the new staff are ready to work with participants.

It’s important to be able to verify that staff indeed meet these minimum hiring requirements. Determining what is considered to be adequate evidence of meeting requirements depends on the jurisdiction, the activities, participant populations, and the organization’s standards (if, for example, they exceed the legal minimums or industry standards).

Evidence of Capacities. Examples of evidence for activity leaders include, but are not limited to:

Qualifications, Certificates, Awards. A document or similar evidence establishing that a person meets certain criteria, particularly regarding technical skills, is known in different parts of the world as a qualification, a certificate, or an award. In this context, these words mean essentially the same thing; certificates (also known as awards) are examples of qualifications.

Established qualifications, if present for a certain topic (such as mountaineering or canoeing), may be established either by government entities or outdoor industry associations. Examples of government-established qualifications include those from the UK, New Zealand, and Iceland.

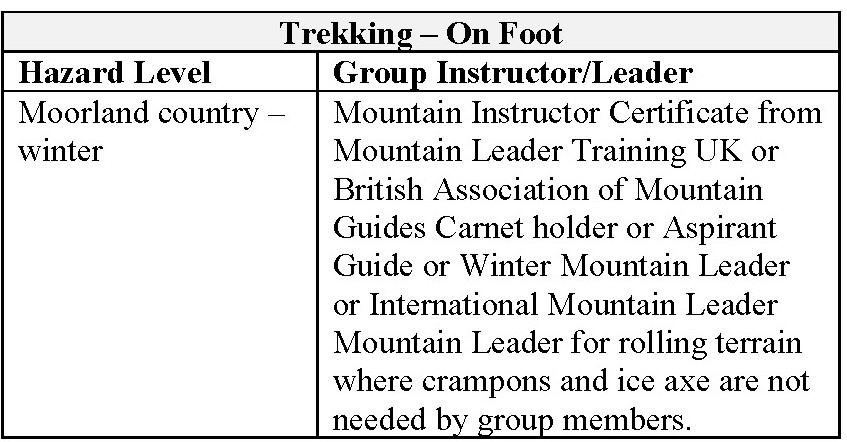

In the UK, the Health and Safety Executive publication L77 (“Guidance from the Licensing Authority on the Adventure Activities Licensing Regulations 2004”) gives detailed information regarding technical competence qualifications for a variety of outdoor activities at various hazard levels. These apply to commercial outdoor adventure organizations regulated under the Activity Centres (Young Persons’ Safety) Act 1995. The document lists, for example, evidence of legally required technical competence for group leaders for foot trekking, as below:

In New Zealand, the WorkSafe New Zealand Safety Audit Standard for Adventure Activities states that staff must have competence for their assigned tasks, using nationally recognized qualifications where relevant. Examples of qualifications include those from the New Zealand Outdoor Instructors Association and those from Skills Active Aotearoa, listed on the New Zealand Qualifications Framework of the New Zealand Qualifications Authority.

In Iceland, the Icelandic Tourist Board Ferðamálastofa, an authority under the Ministry of Industries and Innovation, is working in collaboration with the outdoor adventure industry to establish legal requirements for adventure guide leaders.

Outdoor industry associations, such as National Governing Bodies or peak bodies, have established qualifications for activity leaders. These standards are typically voluntary, and often activity-specific and country-specific. The standards may be published by standards-setting organizations.

For instance, in Australia, knowledge and skills recommended for outdoor activity leaders are noted in Good Practice Guides (GPGs) from the Australian Adventure Activities Standard project. The GPGs refer to competency units such as ‘Select, set up and maintain a bike.’ Those competency units comprise skills sets such as ‘Mountain Bike Guide (Intermediate Environment).’ Those skills sets lead to qualifications such as ‘Certificate III in Outdoor Recreation’ from the Sport, Fitness and Recreation Training Package of the Australian government’s training initiative. The 2015 version of the package includes units for climbing, kayaking, bushwalking and many other outdoor activities as well as managerial topics within its more than 8,400 pages.

The Association for Experiential Education requires that program personnel of adventure programs accredited by the association have at least 16 hours of wilderness first aid training when transport to definitive care is an hour or more, and at least wilderness first responder training (typically at least 70 hours) when transport is four or more hours.

Outdoor Adventure Leader Registration. Evidence of appropriate capacities may be suggested by registration of an activity leader in an appropriate outdoor adventure leader registry, where available. The Outdoor Council of Australia’s National Outdoor Leader Registration Scheme is an example.

Prior Experience. Particularly when a qualification is not available (for example for an unusual outdoor activity), or when hands-on experience is useful in addition to training, prior experience can provide useful evidence of capability.

This is only the case, however, when the experience is of high-quality program operations, so care should be taken when evaluating prior experience. For example, the New Zealand rafting industry in the 1990’s was criticized for having low standards of safety and training, and resistance to making improvements despite multiple deaths. (Standards have since improved.)

References. Thorough and deliberate checking of professional references (generally three or more) of prospective staff is valuable in assessing a candidate’s proven capacities. Not a formality, these reference checks should be conducted in a diligent and searching manner, both to root out potential deception in application materials and to provide a fuller picture of an applicant’s strengths and growth areas.

Interviews. A well-developed standardized employment interview process, conducted in accordance with professional practice, is a requirement for adequately assessing potential future safety performance.

Risk to the business is minimized when interviews and other elements of the hiring process are conducted in accordance with applicable non-discrimination requirements. Interview questions and casual chatting before and after interviews should therefore be careful to avoid direct or indirect questions around characteristics protected by law in the jurisdiction, which may include marital status, religious faith, or many others.

Specialized Assessments. Criminal history, results of drug tests, relevant medical history (such as medical restrictions on strenuous activity), and documenting establishing legal authorization to work can be assessed as appropriate.

Verifiability. The organization must be able to verify it has conducted an appropriate assessment of the candidate’s suitability for the position. Evidence may include, but is not limited to, an applicant’s criminal history record, drug test results, medical health history form, professional resume or curriculum vitae, outdoor resume listing outdoor activity history, cover letter, application form if applicable, references or a record that references were checked and found to be satisfactory, interview notes or records noting a successful interview, motor vehicle operation records, and copies of relevant outdoor industry certifications. These materials should be kept securely on file.

For managers, the same principle applies. Certifications, diplomas and degrees, and job history provided in application materials should be verified to avoid misrepresentation or fraud.

III. Train to Meet Work-Ready Capacities

A staff person new to the organization, no matter how great the previous experience, needs additional training in order to manage risks unique to your outdoor program context. This training should verifiably indicate that the staff person has the capability to execute their professional responsibilities.

Activity Leader Training. Before leading activities, program staff should receive demonstrably adequate training in several topics, such as:

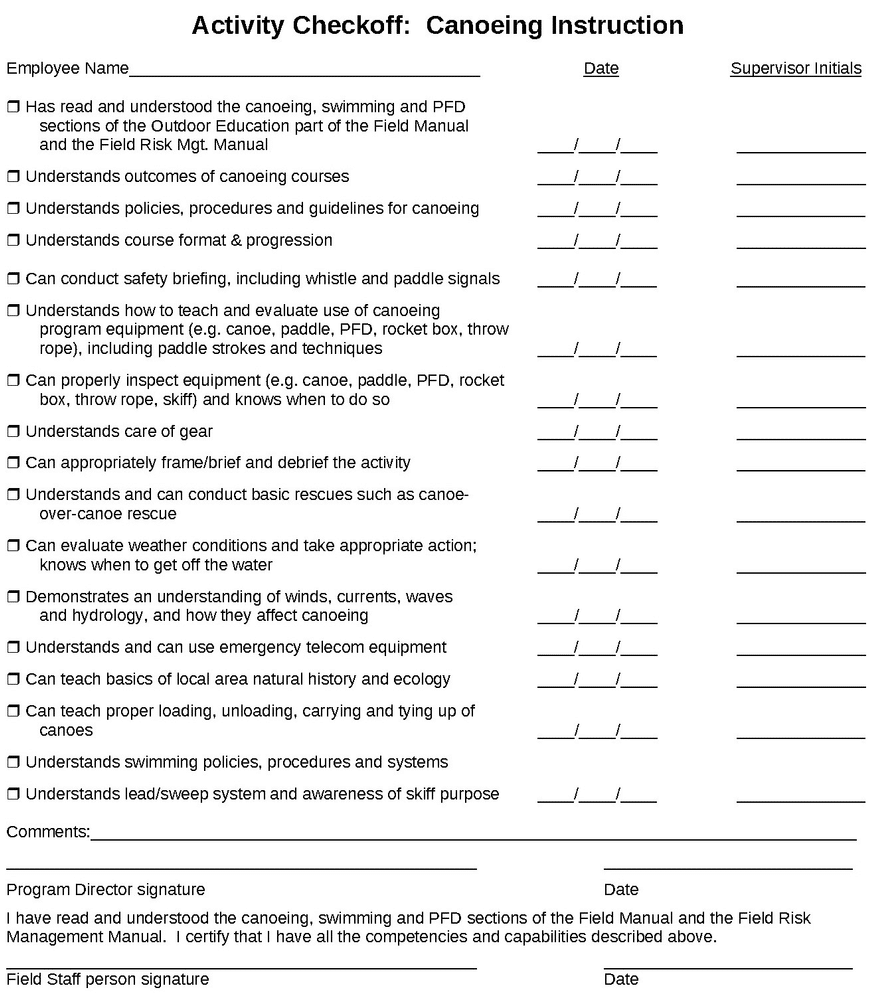

- Activities and Program Areas. This includes the hazards and risks of the activities and the areas in which they are held, and their management, including emergency procedures. It also includes technical skills training and hands-on experience if needed. This training should not be a formality; rushing through orientation to an outdoor program’s activity areas has been cited as a contributing factor to outdoor program fatalities. Check-off documents filled out by a qualified person describing required competencies and documenting their attainment can help ensure that the necessary capabilities are in place.

- Equipment. This includes gear and supplies used for activities and emergency response.

- Participant Populations. Training topics may include supervision, behavior management, medical condition management, and procedures for special populations such as persons with disabilities or a history of behavior problems.

- Cognitive and Interpersonal Skills. Although managers aim to hire individuals who already possess these skills, additional training in topics such as judgment, decision-making, and communication, particularly in emergencies, can be useful. (See Human Factors in Accident Causation, below.)

- Emergency Management. Training in the organization’s safety systems and Emergency Response Plan should include exposure to written emergency plans (to which staff should always have ready access), and experiential training through disaster drills. Realistic, hands-on training is essential; simply reading documents is insufficient. Going through past incident reports and reviews is also useful.

- Specialized Training and Qualifications. This may include successfully completing motor vehicle operator training, orientation to legal requirements such as reporting disclosure of child abuse, or a review of the organization’s medical protocols and authorization to provide medical care.

The organization should be able to provide reasonable evidence that staff have been suitably trained in the appropriate topics. Evidence should generally include:

- A record of required training topics, along with detailed content, outlines or lesson plans

- Verification of attendance, such as sign-in sheets at trainings

- Verification that trainees have the appropriate knowledge, abilities, skills, and values. This can include:

- Check-off documents

- Observation of performance during disaster drill

- Signed documents attesting to having read required readings such as safety reports, Emergency Response Plan, and Risk Management Plan

- Written and practical driver test forms

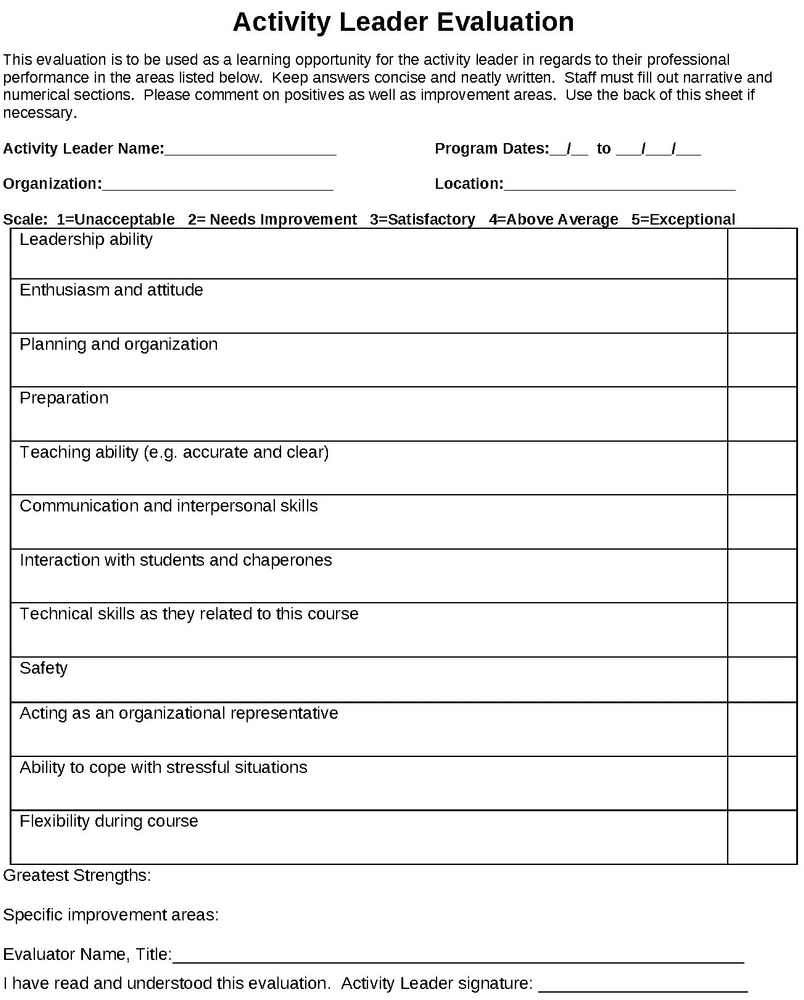

- Assistant leader evaluations and any other performance evaluation documents

Administrator Training. A similar process applies to training of program managers. A verifiable record of appropriate training should provide evidence of trainee competence in areas such as:

- Understanding and applying the organization’s risk management philosophy, methodology, and Risk Management Plan

- Appropriately conducting the administrative components of the organization’s Emergency Response Plan

- Managing media relations during crisis

- Use of the medical screening system (for medical screeners)

- Managing workplace safety issues

- Administrative leadership of safety reviews, incident reviews, staff training, and business administration systems

Office and Administrative Training. All employees and volunteers who may use the organization’s facilities should be able to manage office-oriented risks. This includes the ability to identify emergency exits, use fire extinguishers and first aid kits, and participate in emergency response such as evacuation from the office. A new employee orientation checkoff form covering these topics and kept in each employee’s file may help ensure orientation to these subjects occurs.

Culture. As all training and similar activities occur, it’s appropriate to pay explicit attention to how the words and actions of trainers and authority figures establish corporate culture. Messages that overtly or implicitly convey a culture of conservative risk management are beneficial as new team members absorb organizational norms.

Curriculum Design in Training. To be effective, trainings should be well-designed. Summaries of three principles of curriculum design are briefly outlined here.

Structure. Well-designed curricula have three principal components:

- Goals. These are the explicit learning objectives of the training.

- Lesson Plans. These are the detailed descriptions for each discrete learning activity, targeted to meet the goals.

- Assessments. These are tools that show whether students successfully met the goals, after completing the learning activities.

Methodology. Risk management trainings in outdoor programming are often most effective when they employ the following educational methodologies:

- Experiential learning. Direct experienced followed by focused reflection.

- Scaffolding, or constructivism. Learning builds upon and relates to previous knowledge.

- Progression through learning domains. Learning proceeds through a sequence of learning domains (such as Bloom’s taxonomy), moving through knowledge to application and synthesis and beyond.

Alignment. All aspects of the organization’s risk management systems and risk management training infrastructure are closely and intentionally aligned.

- Risk Management systems. The organization’s risk management infrastructure (including risk management philosophy, mission, policies and procedures, Risk Management Plan, Emergency Response Plan) are organized and documented.

- Training Plan. A Training Plan exists for the organization, and covers

- What should be covered (all risk management topics and information in the risk management systems in the previous bullet point)

- Who should be trained (broken down by categories such as activity leaders, vehicle operators, various layers of management, etc.)

- When training should occur (for example, before working with participants)

- How often training should occur or be refreshed (for instance, annually) for each topic for each audience.

- Lesson Plans. Lesson plans (or “learning activities”) for risk management trainings, and their associated syllabi, are aligned with the training plan (bullet point two), which is aligned to completely cover the relevant topics of the risk management systems (bullet point one).

- Assessments. Evaluation instruments are matched to each learning activity in the risk management training system.

IV. Sustain Capacities, and the Performance They Engender

A fantastic staff team has been hired and trained, and is running outstanding outdoor programs. Clients are thrilled. How to sustain excellence?

Activity Leaders. Staff in the field maximize risk management performance when they work within an established supervision structure that provides guidance, coaching, recognition and discipline. Formalized evaluation systems encourage good performance; evaluation tools can include direct observation; written evaluations by supervisors, supervisees, and peers; and indirect evaluation instruments such as incident reports, post-program debrief forms, land manager feedback, and season-end exit interviews. These and other documents such as commendations and reprimands should be kept on file.

A just culture environment also supports good risk management.

Professional development and advancement opportunities maximize staff engagement and retention, and ease the often chronic problem of high staff turnover in outdoor programs.

Ongoing training, as part of the organization’s established Training Plan, should keep staff apprised of recent incidents and learning from them, and any changes in policies, procedures or practices.

The outdoor program will benefit from having a system that reminds staff to renew expiring certifications (such as first aid certificates) prior to their expiration, and otherwise ensures required qualifications stay current.

Particularly with busy seasons and extended outdoor expeditions, time should be built in for staff recuperation and rest.

Clear written criteria should be developed and followed for promotion of staff. Documentary evidence should be kept showing that staff have met advancement criteria.

Managers. For administrators and other staff, the same principles apply. For instance, any staff person who might be involved in responding to a crisis should go through annual training and practice in the program’s Emergency Response Plan.

Retention. Keeping high-performing staff, who are expert in the organization’s programs and safety systems, is an important business objective. Approaches to this complex topic include:

- Establishing and tracking retention goals, and developing strategies to meet objectives

- Surveying staff on engagement and retention topics

- Maximizing compensation, professional development, and other benefits to the extent possible

- Advancing staff through the organizational hierarchy, as possible, to sustain high engagement

- Maintaining a positive and supportive organizational culture

- Addressing systemic barriers to retention in the industry, such as financial constraints

Summary

We began this article by noting that the human resources function is an important element in risk management for outdoor programs—indeed, for the safety and well-being of any organization.

We mentioned how this simply means applying good HR practice to outdoor programs. Practices that should be specifically shaped to optimize safety in outdoor programs include:

I. Establish required staff capacities

II. Hire staff to meet baseline capacities

III. Train staff to meet unmet capacities

IV. Supervise and support staff to maintain capacities

While it’s easy to recognize in theory that these standard HR practices indeed should be done, it’s more challenging in real life, where HR managers face time constraints, financial pressures, cultural barriers, and other obstacles.

Nevertheless, the importance of good human resources management in outdoor safety should be a priority for all outdoor programs that wish to show excellence in risk management.

This material adapted from the textbook Risk Management for Outdoor Programs: A Guide to Safety in Outdoor Education, Recreation and Adventure.