by Shantanu Pandit

Editor’s Note: This guest article on Viristar’s blog was written by Shantanu Pandit, a long-time leader in the mountaineering and outdoor education fields in India.

These thoughts are a direct result of a course titled ‘Risk Management for Outdoor Programs’ conducted by “Viristar” which I attended in June 2021 and a subsequent discussion initiated by Jeff Baierlein, the creator of the course and our facilitator on the course. It has resulted in this attempt on my part to objectively look at some of my experiences which have deeply impacted me as well as certain developments that have happened in the world of ‘Outdoor Programs’ (programs organised by experts for participants, distinguished from ventures undertaken by adventurers on their own responsibility) in Maharashtra, my home state, and a few other regions in India till today.

Drawing from elements of the ‘Risk Management for Outdoor Programs’ Model, this article considers aspects like, to name but a few here, facets of outdoors culture as it existed at various points of time, societal awareness of adventure and Outdoor Programs, effects of growing numbers of people taking to the outdoors, possible milestones in advancement of concepts in outdoor education, evolution of government policies and regulations, and a few ‘human factors’. In the process, these thoughts helped me figure out almost a progression of things that led to greater and greater safety in Outdoor Programs.

The ‘Risk Management for Outdoor Programs’ Model adopts a standards-approach and looks at risk systemically, focusing beyond immediate causes of an incident. This ‘big picture’ framework helped me a) articulate quite a few thoughts I have had about the why and how of things with respect to events and happenings, b) perceive more of the myriad factors that potentially lay behind specific incidents and events c) discern some forces that influenced a succession of changes involving the evolution of ‘Outdoor Programs’ and safety therein.

To that extent, this contemplation becomes largely my ‘point of view’ or opinion. Any misrepresentation/misinterpretation of what happened and why is solely due to the limitations of my perception and thoughts. My aim is not to draw conclusions but to use concepts of risk management to explore wide ranging developments that affect populations undertaking adventure activities in various formats, and possible lessons to be learnt from same. This narration may serve as a case study to see parallels in other parts of India as well as in other countries, and perhaps help speed things up in efforts that aim at maximising safety in Outdoor Programs.

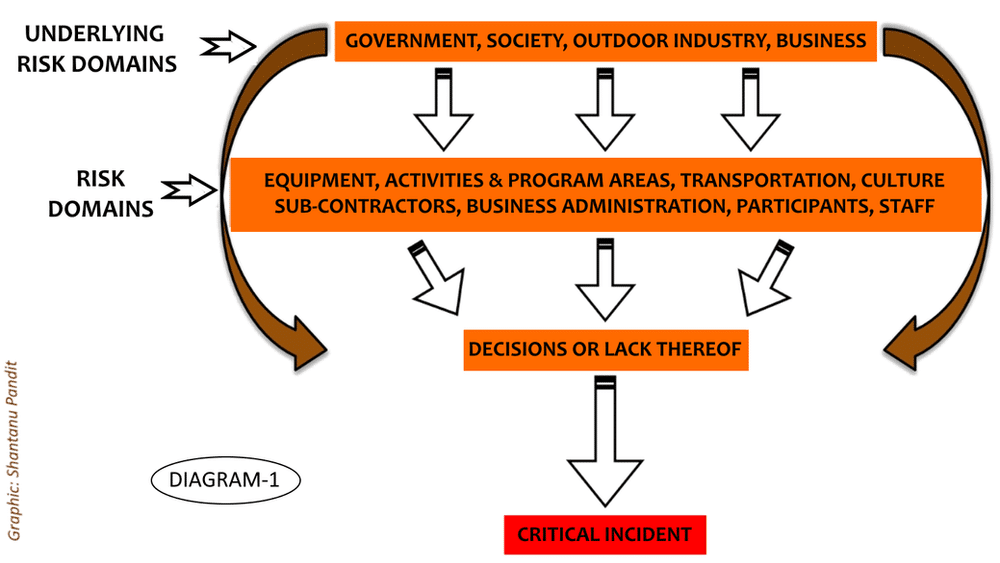

The Risk Management for Outdoor Programs Model (RMOP), very briefly

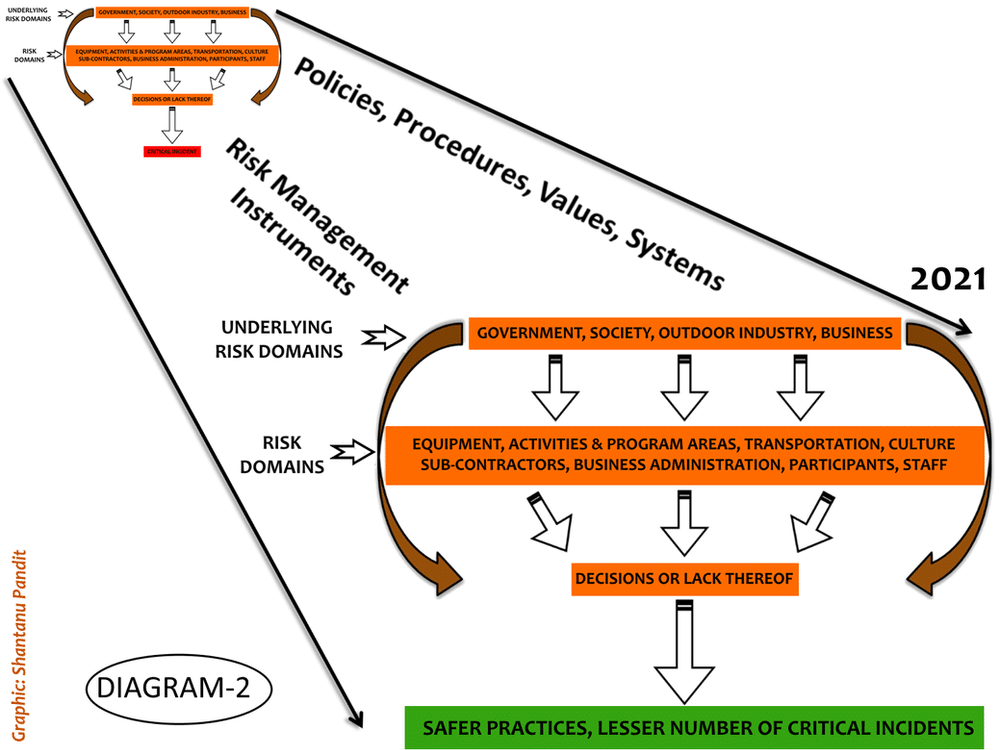

RMOP describes risks as residing in eight risk domains: equipment, activities-and-program-areas, transportation, subcontractors, business-administration, participants, staff and culture. Influencing these domains are four underlying risk domains: government, society, outdoor-industry and business.

To reduce the number of critical incidents and their severity RMOP advocates managing risk by one of the four ways: eliminate, reduce, transfer and accept risk. Risks in risk domains can be managed with specific ‘policies, procedures, values and systems’. And risks across multiple risk domains can be managed with the help of ‘risk management instruments’ that deal with areas of risk transfer and legalities, incident handling, incident reporting, incident review, documentation and a systemic consideration w.r.t. incidents.

In the following content, I will

- Narrate a few stages and events that I think can be indicative of at least some dimensions of the developments that have taken place in my home state and elsewhere in India

- Use elements of the RMOP to look at broader aspects of developments in the field of Outdoor Programs, and offer my points of view (pov) wherever relevant

It may be noted that I write this based only on the information that is available with me, and with the knowledge and understanding that I have gained through direct association in some aspects of these developments referred to above. Any change that is as sweeping as one that embraces government policy and regulation, outdoor community and outdoor field practices spread over many regions in a country will require a concerted effort involving much more data and study.

Defining a ‘starting point’ for this discussion

Background

It was in the 1980s that I took to rock climbing on the ancient basalt of ‘Western Ghats’, the mountain range that runs parallel to the western coast of India. As most Indian hikers and climbers do, I too soon ventured into the Himalaya. My home state, Maharashtra, has always had a strong ‘club culture’ where rookies gather experience under the mentorship of senior club members. Growing up in this culture, I was fortunate to have gotten involved with some dynamic and enterprising individuals who were to play crucial roles in some significant developments that started since then and are still going on.

Our experience in Maharashtra has been that from the 1950s till about mid-1990s, ‘adventure’ was largely undertaken by very few individuals. Society tended to see this activity as very esoteric if not downright eccentric. It was around 1990 that things started changing: in addition to ‘Adventure Projects’ undertaken by adventure enthusiasts we started seeing increased numbers of ‘Outdoor Programs’ where experienced and trained adventurers started taking novices to the outdoors for various purposes including recreation and developmental goals.

To examine developments in the field of ‘Outdoor Programs’ in my home state, it would be appropriate to identify a pertinent time from where things seem to have changed fast and significantly, at least in my perspective. To do this I

- Emphasise the distinction between ‘Adventure Projects’ and ‘Outdoor Programs’: in the former, adventurers undertake risks on their own responsibility and in the latter there are participants who rely primarily on organisers (leaders/instructors/support-staff/etc.) for their safety.

- Will relate a few events/stages that I am aware of and that help me locate a ‘starting point’ for our discussion. There is a core group of people including me who have been associated with or involved in some of these events/stages. Also, these events/stages will be indicative of many aspects that defined the outdoors-environment at various points of time.

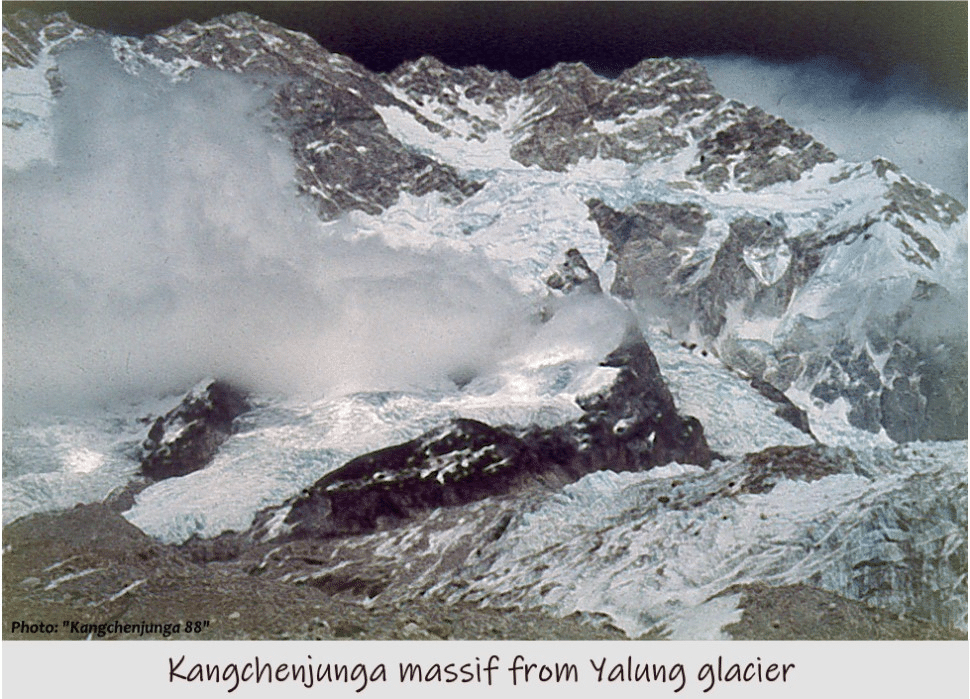

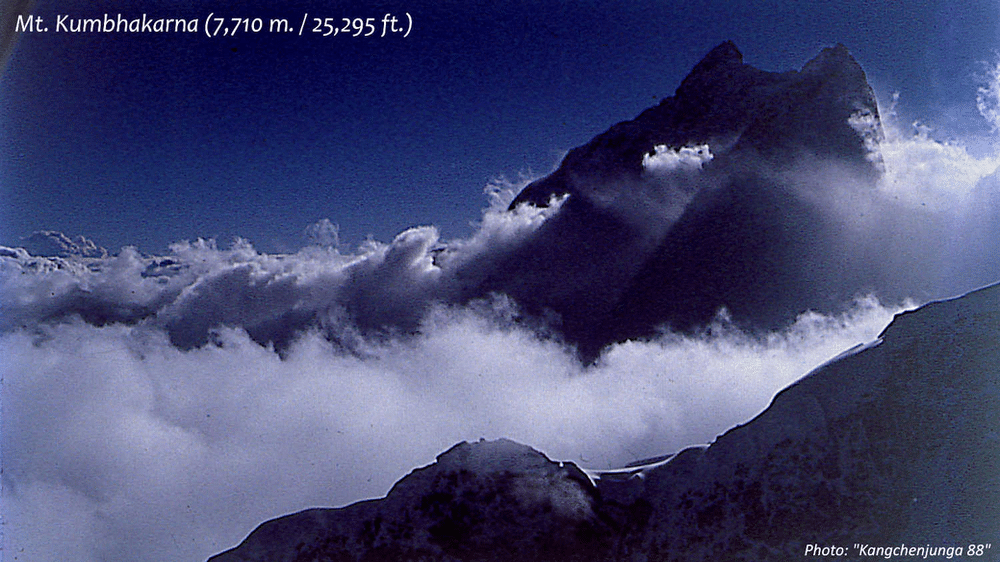

Event: PEAK CLIMBING EXPEDITION IN 1988

In the spring of 1988, I was a part of an expedition that attempted the SW Face of Mt. Kangchenjunga, India’s highest and the world’s third highest mountain at 8,586 m. / 28,169 ft. This was the first expedition to an eight thousander fully organised by civilians in India. The team had both, veteran mountaineers with experience from multiple peak climbing expeditions including to six thousanders and some also a seven thousander, and relatively lesser experienced members. We used the ‘expedition style’ to make our attempt, a style that is also referred to as ‘siege tactic’. To get an idea of the environment that existed in those days, it would be informative to have a quick look at some key aspects of the expedition.

A lot of things about this venture were completely new for us, including a gargantuan budget, public relations and fund raising, equipment procurement, food planning, selection criteria for members, choosing a guiding agency from Nepal, etc. Just to take a couple of examples:

– Equipment: at that time almost all non-government expeditions in India used to borrow equipment from government-run mountaineering institutes in India, there being no other source. These institutes used to have wooden ice axes and leather ‘double shoes’, to name but two items. Such equipment was clearly not suitable for an attempt on an eight thousander and we decided to import state of art equipment from the U.K. This was an expedition in itself, involving sourcing, appealing for waiver or reduction of import duty on mountaineering gear, and getting it cleared through customs.

– Data about the kind of food needed for such an expedition was available largely for western expeditions. Ready-to-eat food, specialised diets and food in dehydrated form were unavailable or not easily available in India. The food-planning team spent months trying to balance weight with calorie values and likeability by the celebrated Indian palate. A stark example: the wife of a member, with the help of people in her small hometown, experimented with dehydrating vegetables and was successful in supplying the venture with required quantities of some items. On a side note, our budget, though huge, could not accommodate expenses of importing food items.

Preparation for any mountaineering expedition is at best a tedious undertaking. Juggling time doing regular jobs/businesses and attending to expedition work, we took more than 18 months to get the venture off the ground. As was the norm then in India for civilian mountaineers (and largely continues to be), we contracted a guiding agency in Nepal for Sherpa guides, a few of whom had been on the SW Face of the mountain.

The Climb

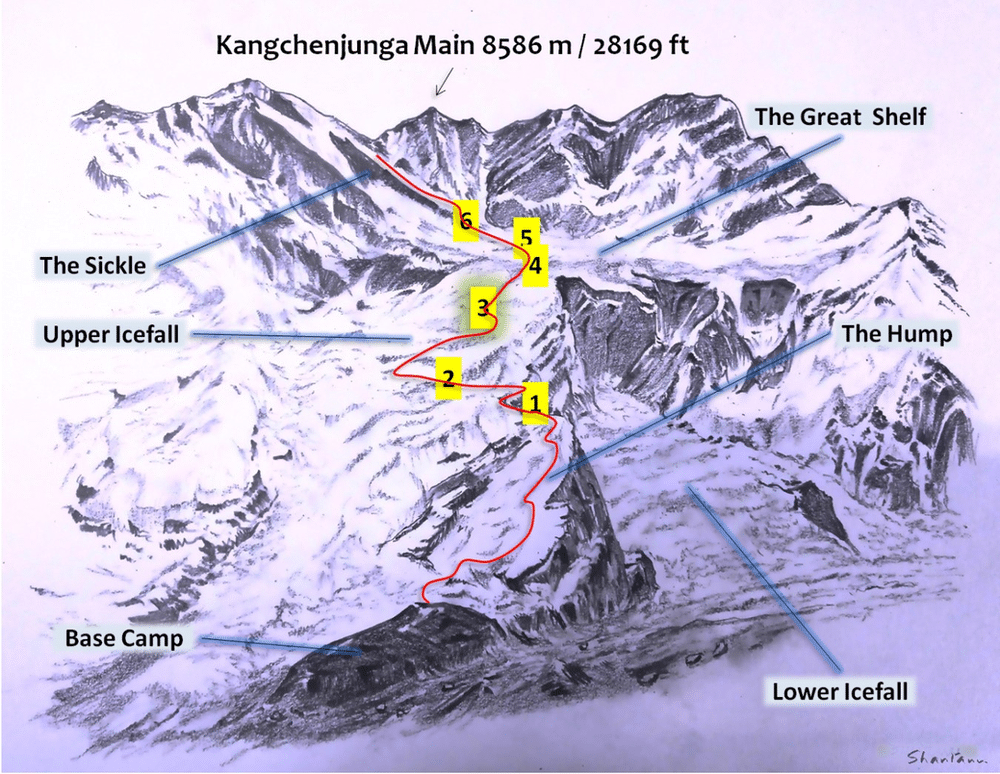

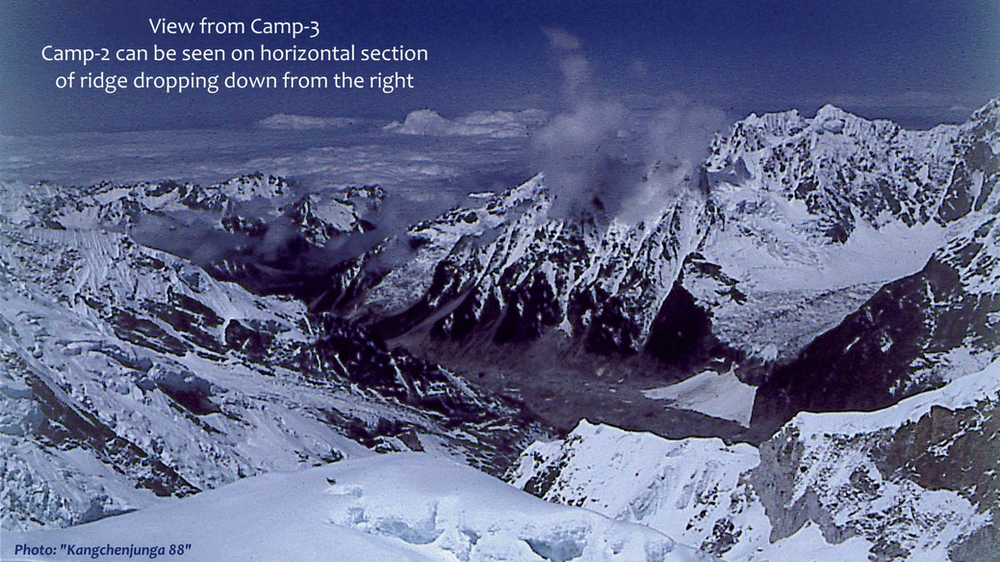

Our base camp (BC) was at 5,486 m. / 18,000 ft. Above BC our expedition had the help of 11 guides (9 Sherpas and 2 Indian locals from the Himalaya). We put up six camps on the face, building up the classic ‘pyramid’ of equipment, food and people up the mountain. Eventually we managed to mount two summit attempts, each composed of one team member and two Sherpa guides. Both attempts were unsuccessful, for various reasons. While the four Sherpas returned with frost-nip on some fingers the two team members suffered frostbite on fingers and toes. With immediate care by the two expedition doctors and further medical treatment in Mumbai, both completely recovered. The Sherpas too fully recovered much earlier. On retrospection, we believe that both summit teams took the right decision to turn back at the right time.

Critical incident on the expedition

At the crucial stage around the two successive summit attempts, several factors came together to contribute to a critical incident.

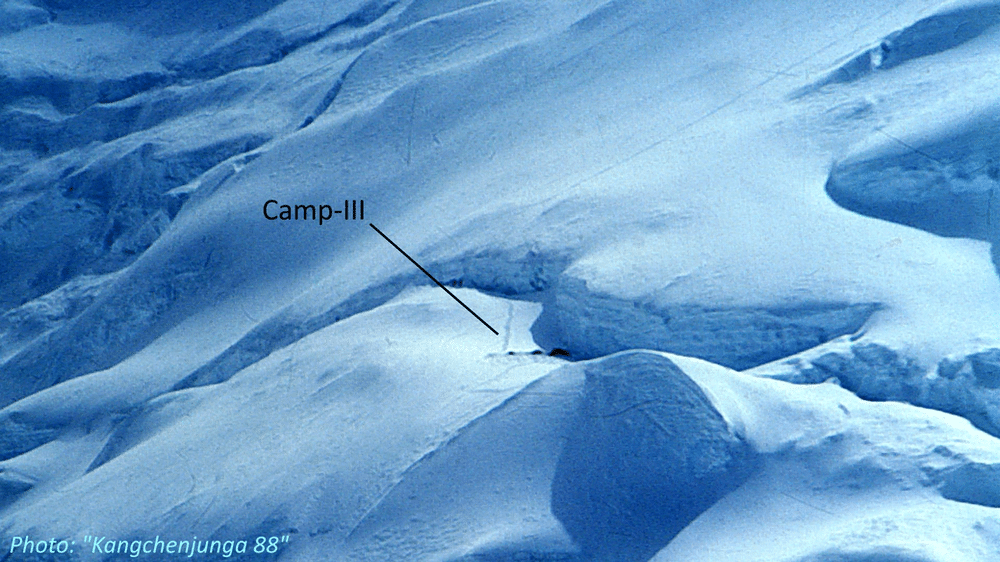

Before the two summit attempts, when I was stationed at our Camp-3 (C3) at about 6,850 m. / 22,500 ft., a storm hit the area, with wind-speeds that made standing impossible. It started at around midnight and abated only by early mid-morning. All tents at C3, pitched on a ledge in the middle of a feature called Upper Icefall, collapsed. Our fixed ropes on the mountain were no longer reliable and needed checking and re-fixing if necessary. That affected supply of gear and food. One effect of that was that the camps above C3 were hit with shortage of food, just when summit attempts were being planned.

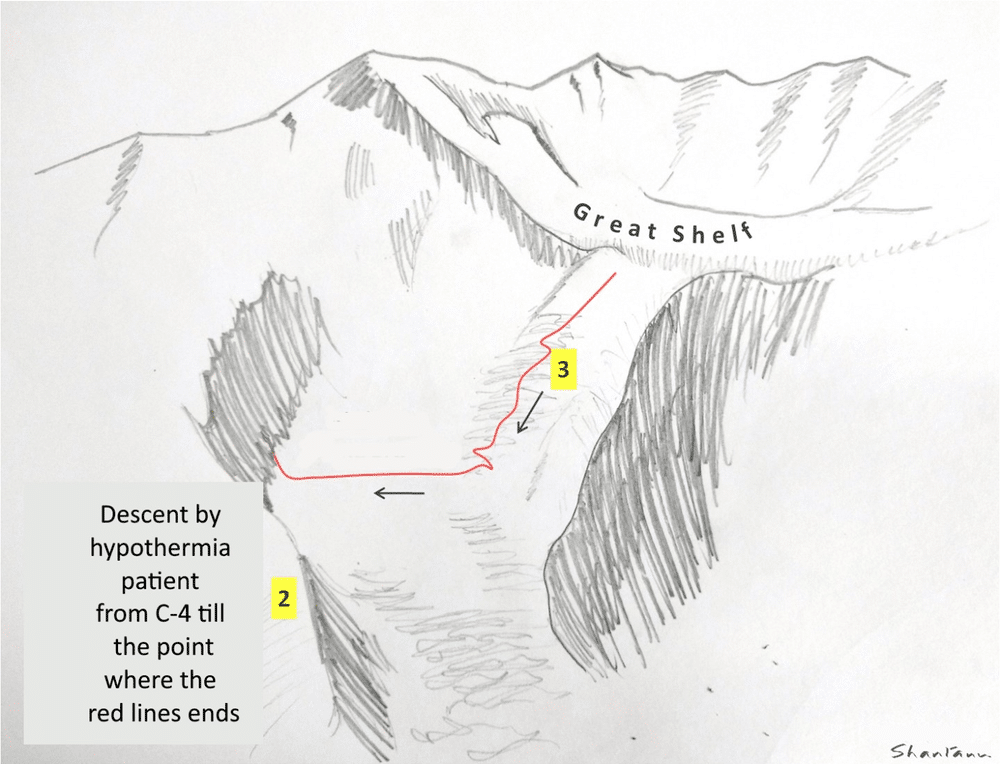

During that period, the expedition leader was stationed at C2 to coordinate the overall movement while the deputy leader (DL) moved up from C3 to C4 (located a little below 7,300 m. / 24,000 ft.). The latter arrived at C4 in an exhausted state. One of the two expedition doctors who was stationed at C2 kept up a conversation with C4, asking team members to check on the DL’s condition. Eventually the DL’s long time climbing partner prevailed upon him to descend to lower camps just before the second summit attempt was made. Meanwhile, I had moved down from C4 because of diarrhea that had persisted despite medication. So I was at BC when we heard that the DL had had an extremely tough time descending down the Upper Icefall and across the huge plateau leading towards C2. But before he could reach C2 he succumbed to hypothermia with powder snow raining down on him from steep cliffs. The failure to reach the summit faded into insignificance against the loss of a friend.

A few thoughts on the critical incident in the context of the RMOP

The RMOP course provides an excellent framework to understand the multitude of factors and forces that affected decisions taken individually or collectively on the expedition. Or, for that matter, decisions not taken. To repeat, the framework enables us to recognise and understand things holistically, though some thoughts expressed below will point towards probable immediate causes of the critical incident.

1. Very high altitude: judgment and decision making are definitely impaired.

RMOP reference: risk domain: Activity Area

My pov: when discussing any such case, whether from the 1980s or 2020s, I always remember what is cautioned: never judge people and their decisions taken at high altitude from a low altitude setting.

2. Till about 1990 the field of outdoors in India largely comprised of non-profit hiking and mountaineering clubs that conducted activities for their own pleasure (though there were a few notable exceptions that conducted adventure travel as a business). While three mountaineering institutes offered courses in hard skills, a few clubs conducted their own rock climbing courses, their duration not exceeding 4-5 days. Courses offering training in areas like risk management and outdoor leadership had not arrived.

RMOP reference: underlying risk domain: Outdoor Industry

My pov: we had appropriate equipment and were adept in its use. I wonder if decisions that affected the DL’s movement could have been made differently had we had a different perspective of handling risk in changed circumstances vis-à-vis team members influencing group decisions.

3. Risk domain: Culture

Some members, from early on, suffered upset stomachs which affected load movement up the mountain; e.g., missed load ferries or climbers dropping down to BC for recovering from illness.

My pov: without touching the topic of the celebrated Indian ‘cast iron stomach’, it is a fact that upset stomachs on hikes and climbs anywhere has never troubled us enough to merit serious attention. I have also at times heard lack of appropriate hygienic practices being glorified a bit.

RMOP reference: the cognitive bias pertaining to the faulty belief that camp hygiene was not something that required deliberate and firm attention. This became critical at high altitude.

4. It would be pertinent to discuss here a few ‘human factors that can lead to incident causation’

RMOP reference: risk domain: People (since there is no true distinction between ‘participants’ and ‘leaders’ in this case)

My pov:

a. The DL had been exposed to very harsh weather during the 8-hour storm which we had sat through sheltering under the tatters of a damaged tent at about 6,850 m. / 22,500 ft.

b. Throughout the climb beyond BC the DL had given in to his likes and dislikes of food and ended up eating less whenever a meal was not to his liking, citing how he felt nauseous if he ate (there were a couple of others too who had similar likes/dislikes).

c. Normalcy bias: some climbers who went above BC seldom dropped down back to BC to rest and recoup. Sustained stay at higher and higher altitudes with diminishing appetites probably affected individual climbers, to varying extent.

5. The triad of low intake of food, increased activity at very high altitude and recent exposure to harsh weather was treacherous, and the DL stayed at C4 (just below 7,300 m. / 24,000 ft.) for two nights in his weakened state, with the camp facing food shortage.

Accomplishments in brief, and moving on…

The following salient features, while bringing to the fore prominent aspects of the mountaineering culture in India at that time, also are perhaps indicative of the people and factors that influenced subsequent changes.

- We were the first civilian group in India that thought of independently breaching the barrier of 8,000 m. / 26,000 ft.

- Our budget was highest by far till then. Raising funds was a massive exercise where countless number of friends, strangers, businesses of various sizes, industrial houses, media, government employees and government bodies helped in every which way, driven by their fascination for the venture.

- It was the first time that state-of-art equipment and clothing in considerable numbers got imported into India (our Defense Forces have had a presence at very-high-altitude since decades due to strategic reasons, but their equipment was obviously inaccessible to civilian mountaineers).

- The two summit attempts had two team members go above the critical altitude of 8,000 m. / 26,000 ft. – this was a huge experience that came back with them.

- After returning from the mountain, we formed a new public trust to which we gave away all our equipment with the objective of making modern gear available on rent to civilian mountaineers at a very low cost. People from all over India came to access it for years.

- The expedition changed the lives of most team members, and people like me moved to outdoors and/or outdoor education permanently despite having educational qualifications in conventional fields. Some members of the expedition eventually got involved in advocacy work that was to influence safety in Outdoor Programs later on.

Project: Outdoor Education Program for Children

It was in 1989, after all the post-expedition work had been taken care of, that the leader of the expedition initiated a new and very inspiring project: to establish an outdoor education centre based on what he had learned in an 11-month course in Scotland a few years back. That project delighted a multitude of adventurers, educationists, school authorities, parents and sundry individuals from all walks of life. Our 5-day outdoor education program (OEP) was solidly based on the theory of education. We had designed a format that leveraged on the features of our local socio-ecological environment. Also included was systematic training imparted to volunteers to teach outdoor education. We soon formed a trust to run the project. Five of the seven trustees were from the Kangchenjunga expedition (either from the climbing team or from the core support team). We received tremendous response from schools. This program probably was truly the first of its kind in India. Our project soon became well known, and donations started coming in out of nowhere and we could easily get media coverage for our events.

A few thoughts on the Outdoor Education Program

1. The content of the OEP made use of local socio-ecological elements to address the goals of outdoor education. This made perfect sense to the fact of it complementing formal education.

RMOP reference: risk domain: Activity and Program Area

My pov: the studied approach adopted by our project spoke magic to everyone who came in contact with it.

2. We set up a process for receiving regular feedback which schools authorities and parents gave us in earnest. We received donations to purchase land and basic infrastructure. We tied up with a city hospital to have interning doctors take turns to stay week after week on the campsite while we were running the program.

RMOP reference: underlying risk domains: Society

My pov: such support helped manage risk very effectively; e.g., a) we prioritised availability of water and could dig a bore-well (tube-well) with the funds donated to us, and b) some illnesses which could have been challenging to regular instructors were dealt with by the visiting doctors.

3. Till 1989, children camps being conducted by a few well known hiking clubs were all ‘adventure camps’ where experienced club members volunteered as instructors.

RMOP reference: underlying risk domain: Outdoor Industry

My pov: The OEP project was the first big step towards a well thought-out ‘Outdoor Program’ where instructors received training inputs in multiple aspects related to outdoor education as well as larger dimensions of the project as an organisation.

4. The OEP brought in a new perspective of looking at ‘outdoor camps for children’. E.g., ‘teaching outdoor skills’ transformed into ‘using activity-based experiences for educational goals’. The concept of outdoor education as was practiced by the OEP hugely influenced instructors as well as anybody who came in close contact with it.

RMOP reference: risk domain: Culture

My pov: one of the most prominent changes that I personally perceived was in ‘leadership style’, or more specifically ‘instructing style’. We instructors received training that helped us move away from being always directive, a style that can be traced all the way to the mountaineering institutes which offer basic and advance mountaineering courses. Just to take an example, our OEP adopted multiple constructive ways of addressing behavioral issues of participants after a discussion with educationists and child psychologists (instead of ‘punishment’).

5. Our project floundered and became defunct after four years.

RMOP reference: risk management for an organisation to ensure sustained functioning.

My pov: the main reason for this was that we trustees failed to nurture it as a long-term entity.

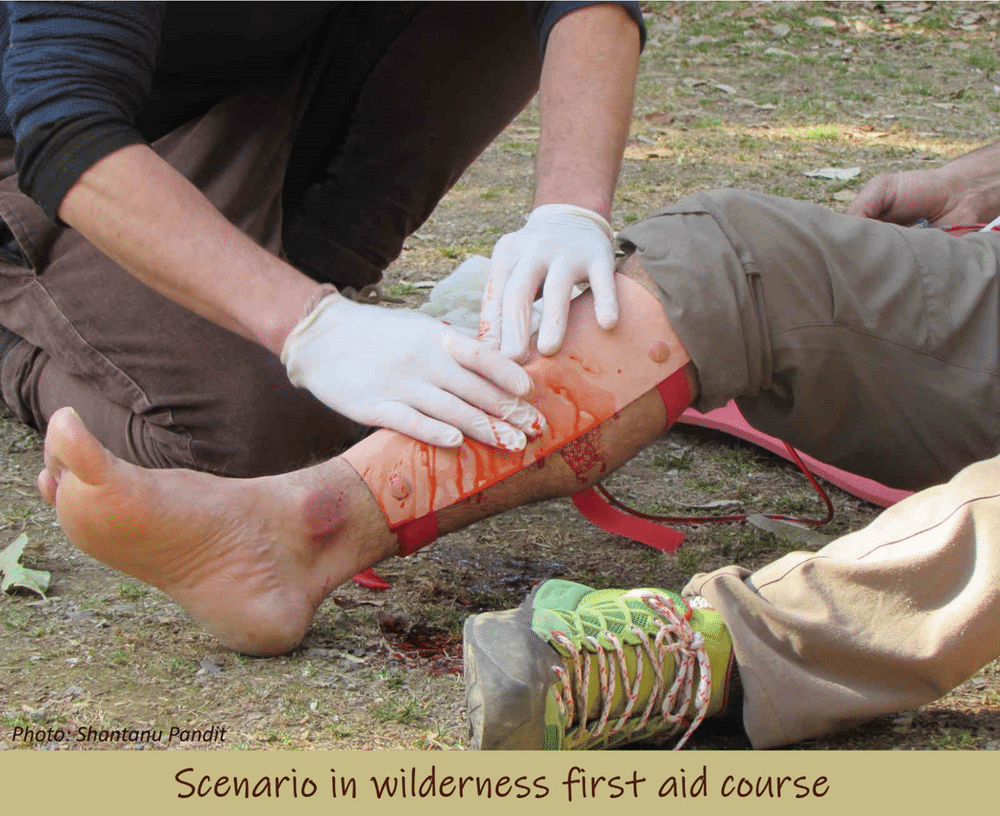

Stage: Formal courses in outdoor leadership and wilderness first aid

Starting from early 2000s, two internationally acclaimed organisations started offering courses in other areas in India for Indians: outdoor leadership and wilderness first aid. The courses offered by these in their own way complemented the hard skill courses that were primarily being offered in India (rock climbing courses and mountaineering courses). In 2010s an outdoor education centre based in the Himalaya started offering both outdoor leadership and wilderness first aid courses. The former has been designed specifically for the kind of work that happens in the variety of Outdoor Programs in India, ranging from ropes courses in resorts to hikes to activity based programs to high altitude treks.

A few thoughts on Outdoor Leadership and Wilderness First Aid courses

1. For reasons like long duration courses and price tags, the response to outdoor leadership and wilderness first aid courses can at best be described as sluggish. Even the more affordable courses being offered by the Himalaya-based outdoor education centre, while accessible to a larger population, still seems to be out of reach for many. Many if not most service providers are either clubs or very small outfits that find it difficult to justify both, the extended time spent by their group leaders/instructors away from work and the cost of such training.

RMOP reference: underlying risk domain: Outdoor Industry

2. Being offered by private entities, these courses do not have any kind of ‘official recognition’. This could be impacting the acceptability of these courses in the outdoor community.

RMOP reference: underlying risk domains: Government

3. Barring a few exceptions, big for-profit organisations offering Outdoor Programs of various kinds have also not responded to the outdoor leadership and wilderness first aid courses, relying instead only on the recognised mountaineering courses and internal training on leadership.

RMOP reference: underlying risk domain: Business

My pov: budgeting for these courses should be much easier for big players, and participation by them could add to the visibility of the value of these courses.

Reflections on developments that have affected Outdoor Programs

In my attempt to look at various dimensions of developments that have happened since 1988 (given that I have defined that period as my ‘starting point’), I will highlight some that I think were the most significant and that have cumulatively contributed to the stages of progress that one can discern in the field of Outdoor Programs, especially in my home state, Maharashtra. These were either driven by deliberate decisions or evolved in the course of events. There is a core group of people who have been involved consistently through these stages of developments in some role or the other, and as stated before, many of this core group have been common in events/stages like those mentioned above.

In addition to risk domains and underlying risk domains as specified by the RMOP, I will also refer to policies-procedures-values-systems and risk-management-instruments to examine events and developments in my home state and in India.

My thoughts expressed below have been influenced by my experiences from the Outdoor Education Program mentioned above, an adventure travel company that I ran as a director for a few years, teaching outdoor leadership in India and the U.S.A., facilitating outdoor management development programs for corporates, voluntary work with hiking clubs, documentation work (safety guidelines, SOPs, paperwork for accreditation) and advocacy undertaken through a non-profit organisation where we successfully influenced state level policy on Outdoor Programs.

Risk Domains and Underlying Risk Domains

1. Underlying risk domain: Government

a. In 1991 the central government in India introduced wide ranging social and economic reforms, the latter being referred to as ‘economic liberalization’. One can perhaps trace a small spinoff of this in the sudden demand for adventure holidays (largely land-based).

RMOP reference: wide ranging policy level decisions taken at the highest authority with a certain purpose can have unanticipated consequences that potentially can affect Outdoor Programs.

b. At different points of time a few government bodies introduced aid in various forms for people to participate in Outdoor Programs and Adventure Projects; e.g., many public sector banks used to grant 1-month’s ‘paid leave’ to an employee participating in a hike in the Himalaya, and mountaineering institutes set up by the government offer courses to Indian civilians at heavily subsidized prices. Such incentives played a useful role in encouraging more and more people to take to the outdoors.

RMOP reference & my pov: one anomaly that emerged was: while funding was received for participation (for some people), there was no funding for training or creating training resources to help organisers and field staff be holistically competent in leading groups in outdoor programs (e.g., wilderness first aid, risk management, group management and outdoor leadership).

2. Underlying risk domain: Society

After 1991, there seems to have been more exposure to unconventional holidaying (e.g., the early 1990s saw a dramatic increase in number of TV channels which brought adventure and outdoor settings into people’s living rooms). People flocked to hiking clubs and newly formed adventure companies for outdoor holidays. This was a fortuitous time for those individual adventurers who were keen to explore a career in the outdoors. This was also the time when schools and corporates started exploring experiential learning as a methodology, and adventurers jumped in to provide exciting experiences in outdoor settings for developmental purposes.

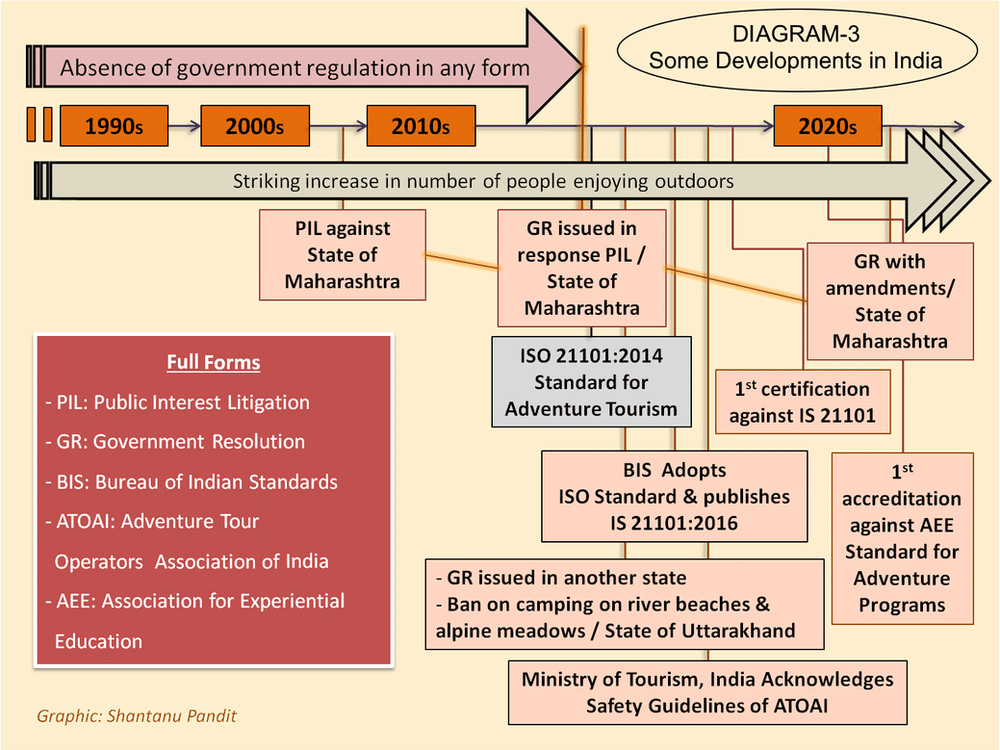

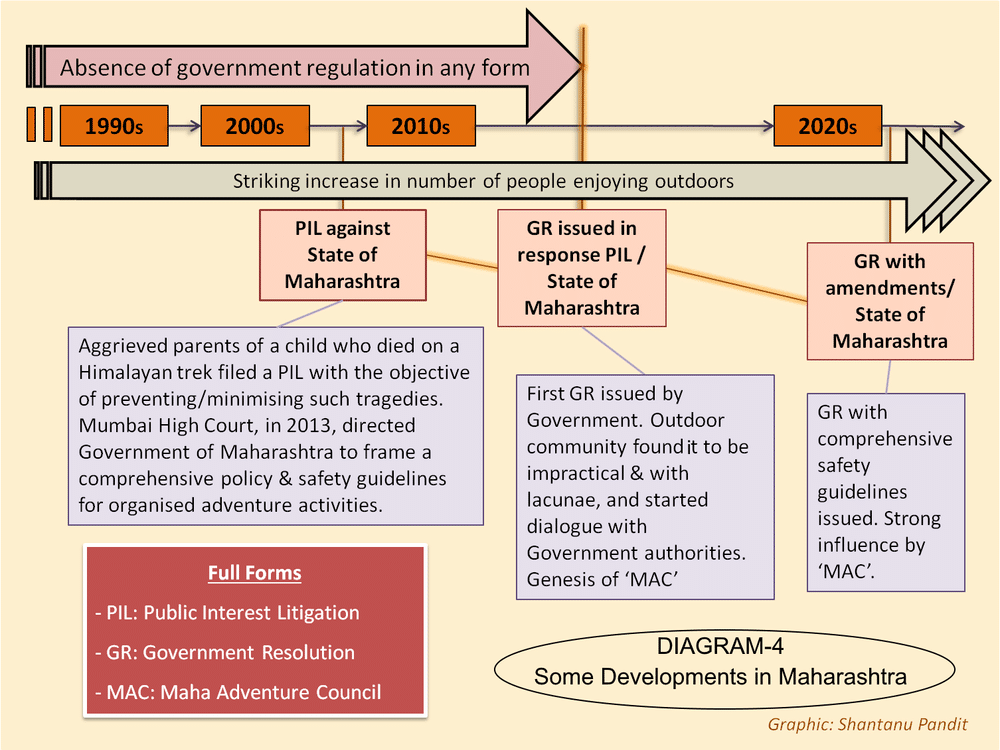

RMOP reference: by mid-2010s, the field of Outdoor Programs (it does not have ‘industry’ status in India) was dealing with large numbers of participants, and the numbers only kept growing. The impact of this on both people and the environment was being very apparent. It then reached a stage where the extent to which risk was being managed was perhaps no longer ‘socially acceptable’. One of the effects of this was the beginning of legal cases being filed in courts by concerned citizens for both, environmental damage and risk to people safety. (Reference for timeline: Diagram-3 below).

Additional happenings:

- 2010s saw individuals working in industrial settings in India going in for training and certification with Industrial Rope Access Trade Association (IRATA)

- In 2020, the first ‘inspector’ in India got certified by Association of Challenge Course Technology (ACCT)

- 2020 also saw the apex body for mountaineering, Indian Mountaineering Foundation, start offering wilderness first aid courses in association with the Himalaya-based outdoor education centre mentioned above under ‘events/stages’

3. Underlying risk domain: Outdoor Industry

a. Outdoor Programs, 2000s to current times: there was a rapid increase in the number of commercial concerns, informal groups and groups formed on social media who started enjoying outdoors through land-, air- & water-based adventure activities.

RMOP reference: to handle groups of novices and on programs that have objectives like recreation and development, specific types of systems and processes need to be in place – my pov is that these started receiving adequate attention and by increasing numbers of stakeholders only after events involving litigation started unfolding in mid-2010s.

b. In the absence of regulation (for safety of both people and environment), the adventure community was left to self-regulate itself when conducting Outdoor Programs – something that has perhaps not been effective across the world in the context of at-scale operations at industry-level.

RMOP reference: with regulation being considered by states in India, it will take a studied approach and concerted effort by all concerned entities and stakeholders to bring about a cultural change in how Outdoor Programs practice safety.

My pov: dissemination of information, proper guidance and accessibility to variety of training resources can play a significant role in helping stakeholders meet the requirements of newly introduced norms and regulations and ultimately maximise safety in Outdoor Programs.

c. A highly encouraging development was when some of us got together to evolve safety guidelines and to try to influence regulation of Outdoor Programs that was being implemented in Maharashtra. We gathered a team with varying skill sets and experience needed to undertake this protracted effort, researched about such events that had happened elsewhere in the world and managed to successfully dialogue with government authorities. With the backing of the august Himalayan Club, we registered ourselves as a non-profit organisation called ‘Maha Adventure Council’ (MAC): ref. Diagram-4 below.

4. Risk domain: Equipment

The 2000s saw foreign equipment manufacturers, including some of the biggest brands, start entering the Indian market, and equipment soon became no challenge for both personal ventures and Outdoor Programs. This is a good factor that works for enhanced safety. The mountaineering institutes too, of course, have modern appropriate equipment.

5. Risk domain: Activity and Program Areas

It was easy for outdoors people to use their knowledge of different locations and capitalise on the network of local contacts to arrange delivery of their service offerings. The resourcefulness in doing so and designing diverse kinds of programs aimed at different objectives has been impressive.

RMOP reference and my pov: (this is only in the context of hiking and rock climbing that is undertaken in the Western Ghats in Maharashtra, the mountain range that runs parallel to the western coast of India). The topography of this terrain is very distinct and has a characteristic set of hazards which sees groups get into trouble (getting lost, falls over drops, dehydration, mild to moderate hypothermia, etc.). But no systematic study about risks in this mountain range has been undertaken, nor is any pertinent information easily available to individuals, groups and organisations wishing to undertake Outdoor Programs in this region. So decisions tend to be taken in the presence of unrecognized cognitive biases and cognitive shortcuts.

6. Risk domain: Subcontractors

Local populations in Maharashtra, mostly villagers, especially in areas most frequented by visitors have gotten involved in many ways in the role of service providers. Adventure companies and clubs tend to outsource operations to subcontractors in the Himalaya too.

RMOP reference: while the boom in adventure tourism benefited local populations financially, they still have no access to comprehensive awareness and education about matters of safety, be it on a subject like camp hygiene or technical systems like a Tyrolean traverse activity rigged up for recreation.

My pov: the existing safety guidelines in Maharashtra refer to this risk domain, but more work is needed on it, as also education of service providers at all levels. MAC has started dialogue with this category of stakeholders.

7. Risk domain: Participant

Participants can be individuals, informal groups, formal groups (e.g., school children, company employees) and parents who send their wards to Outdoor Programs.

RMOP reference: the requisite amount of education for, communication with and seeking feedback from participants tends to depend on individual program organiser. Through the recently introduced safety guidelines, this area is being attended to.

8. Risk domain: Staff

a. With more and more people wanting to do mountaineering and many service providers stating ‘basic mountaineering course’ as a qualifying criterion for a group leader the demand for these courses grew exponentially with waiting lists extending to two years and more. Each course today can have as many as 90 or more students. Given this kind of a group size the authoritative style of instruction makes it practical for conducting a course. Students tend to ‘just follow instructions’ and there is little scope for ensuring that participants gain conceptual clarity behind field practices. This does not do much to improve ‘judgment’ of students.

My pov: the tremendous value of a small student-to-instructor ratio is lost.

RMOP reference: organisations and individuals need to strike a judicious balance between systems-and-processes and managed-safety, the latter being facilitated by good judgment and decision making: an appropriate student-to-instructor ratio has its own influence on this.

9. Risk domain: Safety Culture

Service providers of Outdoor Programs have a big challenge in bringing about a cultural change, now that state governments have started bringing in regulation in India.

RMOP reference: balancing ‘business’ goals with risk management goals, and then accordingly plan for essential investment in enhancing safety is going to be tough in a market that is struggling with costs and price competition.

My pov: for clubs in India, without the burden of conventional targets, it is still a challenge to divert funds from field activities to matters like documentation and new areas of training.

Risk Management Instruments

a. Documentation:

Speaking about a development on international level, ISO published its Standard for adventure tourism in 2014. In India, attempts at regulation by Government of Maharashtra started in 2014, going through various phases. It culminated in a policy on ‘adventure activity programs’ (‘Outdoor Programs’, as referred to in this article) being issued in the form of a ‘government resolution’ (GR) in 2021. This GR includes safety guidelines that have adopted a Standards approach (an area where MAC played a big role in influencing the format and content).

My pov: it seems it has been experienced in many parts of the world that unfortunate tragedies and the subsequent distress in society have prompted formulation of guidelines and regulation.

b. Documentation:

Two voluntary organisations in India have been successful in influencing to considerable extent policy level decisions taken by government bodies.

i. The Adventure Tour Operators Association of India (ATOAI) came up with safety guidelines for land, water and air based Outdoor Programs which were recognised by Ministry of Tourism, India. ATOAI has done other work including trying to get permissions for use of satellite phones in the Himalaya (satellite phones were illegal till recently).

ii. MAC has 1) created elaborate safety guidelines for land, water and air based Outdoor Programs, going beyond the version created by ATOAI, 2) had extended dialogue with government bodies in State of Maharashtra which has come out with a regulatory policy on Outdoor Programs, and 3) started reaching out to various stakeholders affected by the regulation, with the goal of spreading awareness and to some extent educating people in what to do for enhancing safety in Outdoor Programs.

c. Accreditation:

Two ‘firsts’ happened in this period in the area of accreditation and standards-certifications. (See Diagram-3 above).

RMOP reference: accreditations and certifications-against-international-standards play an important role in contributing to risk management.

My pov: these two cases are excellent examples of private entities responding to changes and can prove to be role models in India.

d. Risk Transfer:

Till recently it was difficult to get appropriate insurance cover for adventure activities. One company now offers “approved policies to provide India’s first comprehensive sports & adventure cover”. MAC will study this complex field further and contribute to developments.

e. Processes and Systems to prepare for, manage and close critical incidents:

While elements in this set of risk management instruments exist in some form or the other for Outdoor Programs, there is a need for more comprehensive implementation of same. Necessary expertise in the form of trained and experienced individuals to form entities like risk management committees is not easily available (probably exists in the form of a handful of individuals). The safety guidelines inherent in the newly introduced regulation in Maharashtra include some such elements, but will need to be revised further, along with creating resources for required training to support this instrument.

In conclusion

It is educative and yes, intimidating, to realise the sheer number of factors and forces that lie much beyond immediate causes of incidents, influence one’s decisions and contribute to changes in the development of outdoor industry. The moot question is, does such contemplation remain largely an academic exercise? In my experience, such reflection is nothing new in many areas of our functioning. For instance, the corporate world is known to address ‘learning & development’ holistically at an organisational level in order to bring about a cultural change.

I believe that such reflection as this article can benefit us in the following ways:

- It can shift focus from blame to understanding the big picture of any incident, and hence address factors comprehensively in order to maximise safety

- It can lead to self-awareness, and an awareness about the immediate and broader elements of one’s own environment

- It can help us reduce the incidence of unanticipated consequences

- It can help us learn from what has happened elsewhere

- It can help us adopt a preventive approach and at the least avoid many preventable accidents

Speaking for myself, the preventive approach adopted by wilderness first aid, the empowering approach of outdoor leadership and guided reflection on experiences have made me understand more and more about our functioning in larger and larger contexts, and that has been one of my strongest motivators to get involved in areas like documentation and advocacy.

Shantanu Pandit

With special thanks to Jeff Baierlein of ‘Viristar’ who supported me in multiple ways throughout my effort at writing this and encouraged me no end; Vasant Limaye, leader of the ‘Kangchenjunga 88’ expedition, for his valuable feedback as I struggled through several drafts; and Dr. Milind Chitley and Dilip Lagu, members of ‘Kangchenjunga 88’ expedition, for sharing their experiences and points of view.