Editor’s note: this guest post was written by Alan Champkins, an outdoor education professional in Zambia, and graduate of Viristar’s Risk Management for Outdoor Programs training. The thoughts and opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of Viristar.

Winter in the Drakensberg Mountains of South Africa, July 1995.

A friend and I were on a multi-day hike. Day three involved ascending a mountain pass on to the escarpment of the highest mountain range in South Africa. It was a beautiful winter’s day—crisp, cold, and clear. At the top of the pass, we turned south to head towards our destination for the next two nights. Sandleni cave was a seldom-used but sheltered sleeping spot just over the lip of the escarpment. We had planned to have a day’s rest there before returning to the start via a circular route.

The following morning’s dawn sky revealed high wispy cirrus clouds indicating that the predicted cold front was on its way. We had, according to the last forecast received before beginning our hike, another 36 hours to get off the escarpment, before the system arrived.

After breakfasting, my hiking partner, a keen bird watcher, said he was going to wander about a kilometer west of the cave to see if he could spot any ‘special species.’ The high-altitude valley leading west was wide and open, and the Sandleni Pinnacle opposite the cave was a clear landmark to find one’s way back, so neither of us thought it would be a problem to separate for a couple of hours at most. (Little did we know…)

Several ‘uncanny’ events transpired over the next few hours. I went back to the cave for some soup and to read; my friend walked west for about a kilometer, and found a warm sunny rock to sit on and observe the bird species in the area. Both of us drifted off to sleep! When we awoke a couple of hours later, the cold front had arrived, significantly earlier than predicted. A thick mist had settled across the area, the temperature had plunged close to freezing, and not long after, it started to snow.

My whistle-blows and shouts went unheard. My friend started walking back to the cave, only to find, in a brief moment of the clouds parting, that he was walking towards the setting sun, AWAY from the cave. He realized it was too late to turn around, and his only chance of survival was to continue to head west in the hopes of finding a village.

As dusk descended, I looked at his hiking gear next to me in the cave and knew there was little chance of him surviving the night exposed to the elements. I sorted out my kit, left most of my food—in the hope he would return—and a note for him saying I was hiking out at dawn to go and alert mountain rescue, and should he return to stay put until rescue arrived.

At dawn, I left for an arduous hike in near white out conditions with up to knee-deep snow to raise the call for help. My heart was heavy…

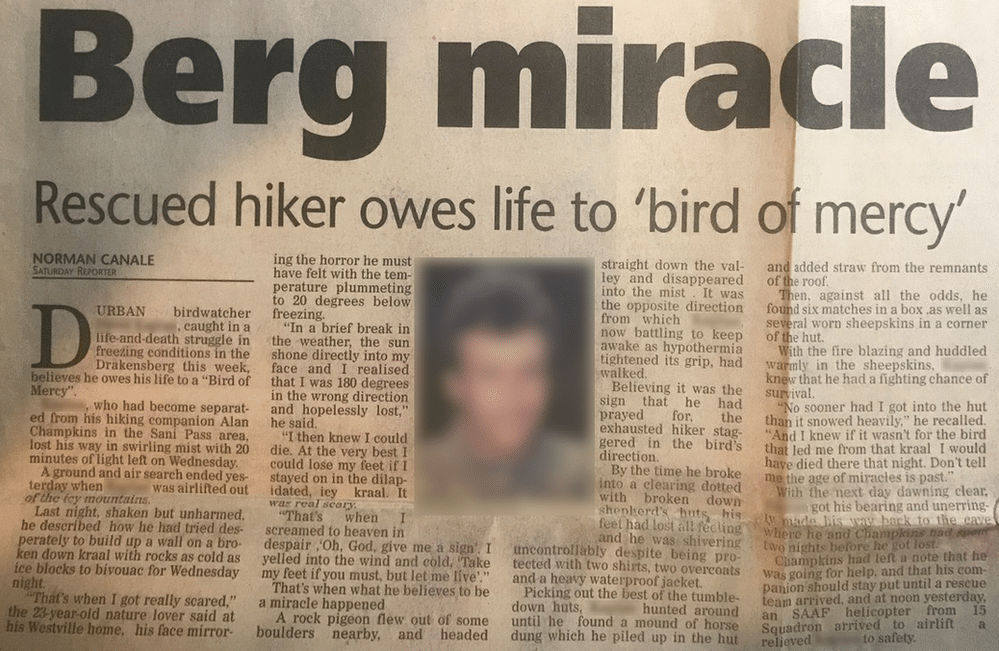

It took a further 36 hours before the mountain rescue helicopter could get to the cave. My friend was there, alive, well, and not impressed at the thought of being rescued. The story made the news and one of the titles in a regional newspaper was “Saved by a Dove.”

“I screamed to heaven in despair, “Oh, God, give me a sign'”…that’s when what he believes to be a miracle happened.

My friend, realizing he was in a hopeless situation, prayed to a higher power for the first time in his life, and at that moment he disturbed a dove and as it flew off, he decided to follow the direction it went. Miraculously, finding an abandoned shepherd’s hut saved his life that night. It could be argued that it cannot be proven that his prayer made a difference or not, but the coincidence of the dove appearing out of nowhere and it flying in the direction of a shepherd’s hut seemed more than coincidental to him at the time.

In the month after, several hiking friends told stories of that area being haunted. The sound of galloping horses had plagued one group all night, only for the group to find that the moment they thought their tents were to be overrun the horses would ‘disappear.’ Another talked of having unexplained encounters in the area. Others of weird dreams, strange weather, and unexplained disorientation. It was a seldom-visited area for a reason!

A century before a person had been killed by ‘friendly fire’ whilst pursuing First Nation cattle thieves in the area. His lone grave was near there and it was believed the area was ‘cursed.’

You may ask what relevance this has to the topic.

Living in Africa comes with many interesting challenges. One of those challenges is around beliefs and superstitions. The Sandleni cave area was considered a ‘no go’ area by local BaSotho shepherds.

There are many such places like that all over the world.

Sacred mountains, caves inhabited by spirits, forests occupied by witches, deep river pools by mythical beasts and water spirits. Nighttime means ‘evil spirits’ are active; owls are bad omens and let’s not talk about lightning! That’s just in the areas I’ve been.

One can be walking through an area when suddenly your local companions will start murmuring amongst themselves and their body language and actions say something is wrong. They begrudgingly continue with you, or may even go the long way round.

In other instances, lightning will strike some distance away, and pandemonium breaks out because culturally it means a shaman is trying to kill someone’s spirit.

Or a noise is heard in the night, and terror strikes a person’s heart because they believe it is a spiritual entity or an evil being, rather than just an owl or perhaps the wind in the bushes.

Others refuse to sleep on the ground because evil spirits will get them.

Or they will kill a snake because it represents something evil in some cultures, without even considering the implications of attacking it.

I have a different story—as a white Christian male, I’ve ‘put my foot in it’ numerous times by ignorantly offending people with my sometimes brazen belief that ‘God will protect me’ or by saying ‘I don’t believe in that stuff’ or even accidentally entering an area that is considered holy and sacred to others.

Our beliefs and values, religious or not, do have an influence on our ways of thinking and acting and this does influence how we manage risk.

I can think of times past when my own way of thinking in the context of my beliefs and values has caused my own unconscious bias to be revealed:

Like when I ‘encouraged’ someone a bit further up a mountainside than what other cultures would consider emotionally safe because I wanted them to understand that God was helping them achieve more.

Or when my own patriarchy ignored the better advice of a younger female group leader because I was of higher position and knew better as a male leader.

Or when I unintentionally discriminated against people of a different faith by showing preference to those ‘like me’ because I believed I had the spiritual and moral high ground and they had to understand me, rather than me accept them as they were.

Or when my own thoughts that “God is in control and will protect me” led me taking an unnecessary risk whilst crossing a flooding stream.

I’m glad that as I get older and more experienced, my penchant for risks is becoming less, and I’m becoming more aware of how my culture and faith determine my biases and influences those around me.

Faith, cultural beliefs, and suspicions, the world over, affect how people live and behave.

Why? Because we ultimately live out what we believe.

Our actions and how we treat people are based both on our values system and our ‘faith,’ whatever that faith may be.

So how does this influence risk and risk management?

Culture has a big part to play in how risk is perceived and managed. Many cultures across the world are based upon that community’s faith, beliefs, or spirituality. Thus, indirectly what people believe not only determines their culture but also how they see risk and manage it.

For some that belief may make them strong. For others it may make them fear. For some it may mean people are sacred, for others a specific area is significant, and for some still, both. Each person’s belief system will determine how they live act and react to circumstances.

In centuries past most cultures and their belief systems were largely separated from others. Today, that is a completely different story—the world has become one big melting pot of politics, economics, cultures, beliefs, faiths, spiritualities and so much more. We’re all trying to get along but at the same time are also needing to keep, find or establish our own cultures and identities.

This makes it very complex and the struggles around that complexity are easy to see in society currently. Some are striving for reconciliation, others for partisanship.

As Outdoor Professionals we interact with a wide range of people. Participants, contractors, and other businesses all come with their own cultures, beliefs, and identities.

The organizations we own, manage or work for come have their own cultures, beliefs, and identities. The staff who work for them their own also.

The culture of each of these risk domains also comes with their own conscious and subconscious biases.

- What one person may see as safe, another might see as a risk and act accordingly.

- What one person may see as only a mountain, river, or forest to be conquered and explored another may see as sacred or to be feared and act accordingly.

- What one person may see as only a night hike in a forest, another may experience as the most difficult thing they’ve ever done and react accordingly.

- What one person may see as a snake to be avoided, another may see as something to be killed without understanding that more people are bitten trying to kill a snake than avoid it.

- What one person may see as an act of encouraging others to believe the same as them, another may see as rejection or an offense and act accordingly.

- What one person may see as misbehavior another sees a rebelling against the culture and belief system they have found themselves a minority in.

I could carry on, but I hope you’re getting the picture.

Different faiths, beliefs and cultures are personal choices. Adherents to a particular faith will claim the positives about their belief whilst others may be neutral, disagree, or even oppose those beliefs. These differences in beliefs can easily become points of conflict, contention, opinion, offense. They can also cause one person of a particular belief to view an event, place or circumstances in a very different light to others, thus creating misunderstandings, offense or even enhancing risk.

As Outdoor Professionals it is important that we have a greater understanding of how our beliefs impact our culture, and how the beliefs and culture of the community and areas we operate in, and the beliefs and culture of who we are working with, intersect. We need to understand how these factors can work together respectfully or can become a point of risk and require careful risk management.

Ultimately, faith and belief determine, rightly or wrongly, how we live, and how we interact with others and our environment. It cannot be separated—we live what we believe.

Beliefs, behavior, and risk management is a complex and sensitive topic. It’s not something we need to explore in depth, but I do believe it is important to understand that what we believe and value influences how we act, react, and manage people and situations. It’s something to keep in the back of our minds as the world becomes more of a melting pot and we work with people and communities of various belief systems.

In closing, we had an event recently that brought home how important it is to understand other people’s beliefs when it comes to risk management. Our team had taken a group of students on an expedition to a mountain several hours from where we operate. It is a customary requirement for the chief of the area to give his blessing to anyone climbing the mountain, and he needs to do it in person. But this time, when we arrived, he was away and when we phoned him, he refused to let us proceed without his in-person blessing. We could have pushed the issue or maybe defied his instructions. Both would have had serious socio- political consequences. Rather, we honored his request and changed the itinerary at the last minute to an alternative area, so as not to cause problems and offend his authority, culture and beliefs. To me, that is what understanding a particular group of people’s beliefs influences how risk is managed.

Have you ever experienced anything similar in your capacity as an outdoor professional? Do you think beliefs influence behavior, and thus are relevant in how you manage risk in your own outdoor programs? I’ll leave it with you and your team to discuss….

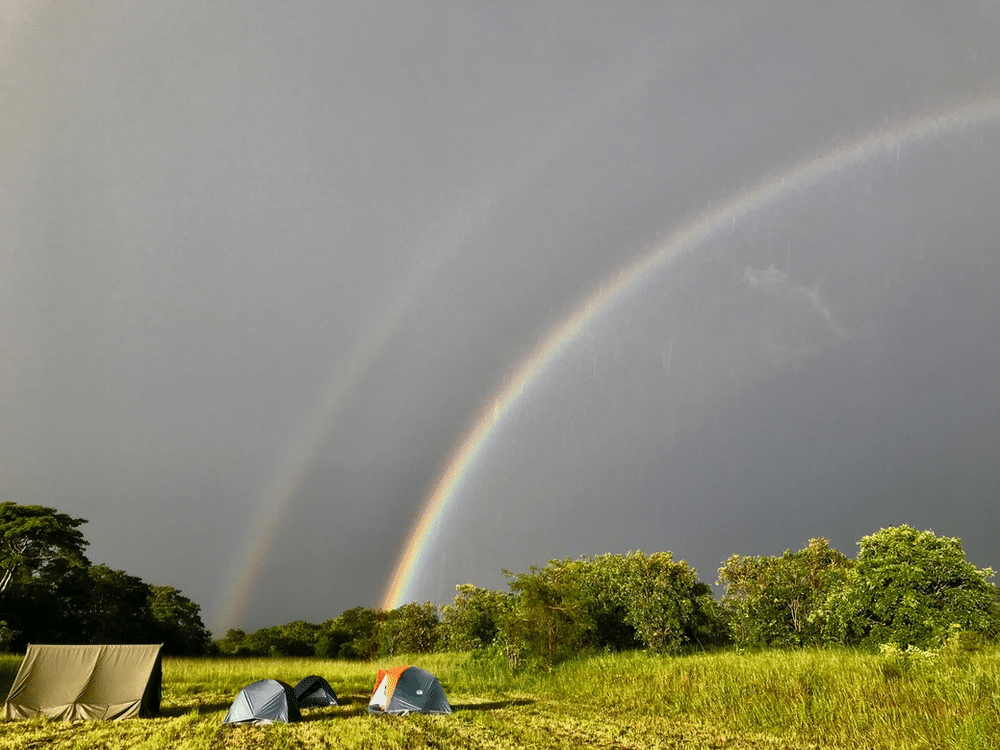

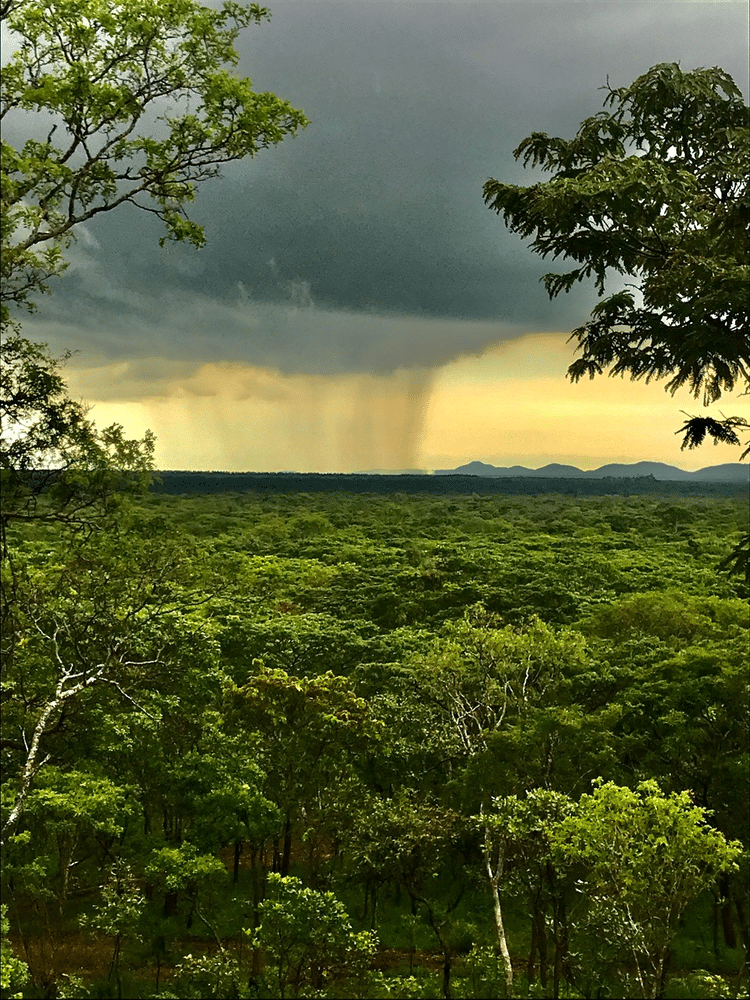

Alan Champkins is the Head of Ndubaluba Outdoor Centre, in Zambia. He writes in his own personal capacity out of a love for the outdoors, a love for people and a desire to see the benefits of outdoor adventure being experienced safely across multiple spiritual, cultural, economic and social boundaries.