Outdoor Safety in America’s Greatest Wilderness

It was late in the day when the chainsaw slipped. Bob was doing a tricky bit of cutting, leaning over a slope with the chainsaw positioned between his legs. He was by himself, clearing a wooded area to build a house. The whirring chainsaw blade bit deep into his calf. Bob collapsed onto the ground.

Bob tried standing up, but each time he put weight on his injured leg, he fell to the ground. He knew he had to get help. But this was rural Alaska, and Bob homesteaded a steep 40-acre patch of old-growth forest and muskeg on isolated island in “Southeast,” Alaska’s southern panhandle. There was no one nearby.

On his hands and knees, Bob crawled back to his 300 square foot cabin. Blood pumped out of his wound at each move. He thought, where did I store my first aid kit? Then he remembered: high in the loft, up a ladder his injured leg could not carry him. Bob crawled across the cabin and grabbed a box of baby wipes. He packed the wipes, one by one, into the wound. He found a roll of duct tape and wrapped the wound closed.

Weak with loss of blood, Bob knew he needed advanced medical care. The nearest medical facility was a clinic in the tiny community of Gustavus, miles away across the cold and open waters of Icy Strait. It was dark by now, and not safe to attempt the journey in his tiny boat. There was no place on the heavily wooded island for a rescue helicopter to land.

Bob crawled to his two-way VHF radio. He called for help—for someone, anyone—to come. From a neighboring island, a resident picked up his call. The neighbor motored over to Bob’s location as he crawled to the shore, where he toppled down a small cliff into the Samaritan’s boat. Bob was carried to the mainland, where his wound was treated.

This is wilderness medicine, Southeast Alaska style.

Alaska: Where Wilderness Areas Call for Wilderness Medicine

Alaska! The biggest US state, home to sparkling fjords, lush rainforest, glacier-clad peaks. It’s a land of vast wilderness and extraordinary natural beauty. And a land of outdoor safety risks ranging from frigid waters to grizzly bears.

Southeast Alaska, the ‘panhandle,’ is a strip of coastline and thousands of islands stretching 500 miles along the west edge of British Columbia. The traditional home of the Tlingit, it’s a rainforest with brown and black bears, bald eagles, wolves, and few people, with most settlements reachable only by plane or boat.

How remote is Southeast? Population density in the USA averages about 80 people per square mile. (In New York City, it’s over 28,000.) New Jersey: over 1,000 people per square mile. But Alaska’s population density is just one person a square mile. And Southeast? Half that.

Bob’s wound healed, but he hadn’t forgotten the need for first aid skills in remote locations. The island where he lives is 11 square miles—mostly Congressionally designated Wilderness. Its population in the 2000 Census: one. But it isn’t the only isolated spot in Southeast. Bob had gained his Wilderness First Responder certification through Wilderness Medical Associates, and wanted to bring WMA’s training to more residents in the area.

Wilderness Medicine Comes to Kake, Alaska

The Tongass National Forest spreads across Southeast Alaska. At 17 million acres, it’s the largest National Forest in the US. (It’s larger than Belgium, the Bahamas and Belize—combined.) It contains millions and millions of acres of federally designated wilderness. And though ecologically devastated by decades of runaway logging, some wild character remains.

Surrounded by the Sitka spruce and salmon streams of the Tongass, on a remote island 100 miles south of Juneau, lies the beautiful village of Kake.

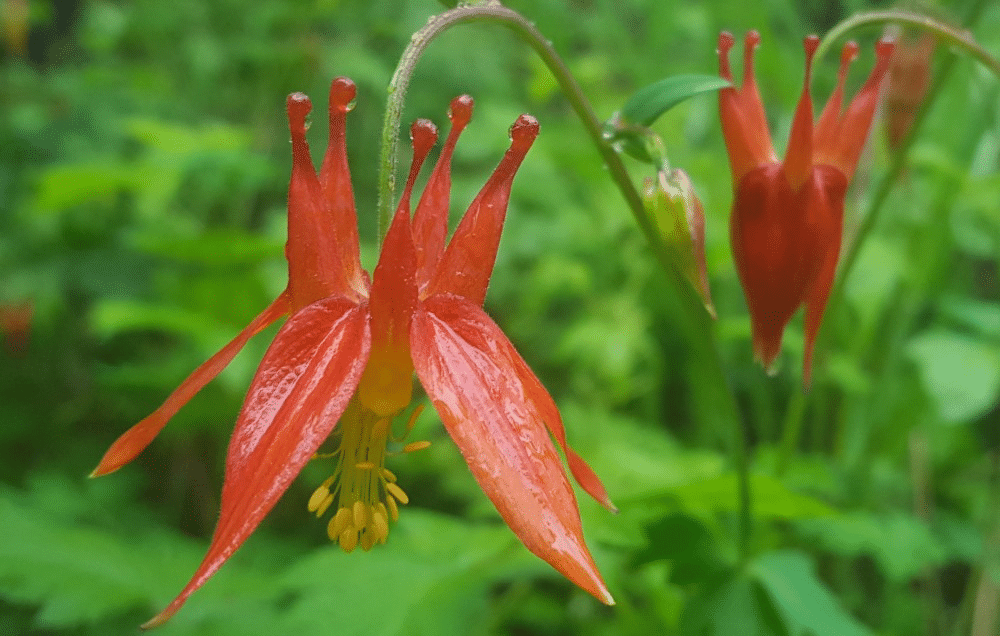

For thousands of years, the Kake tribe of the Tlingits lived in the Kake area, hunting, fishing, and gathering plants and berries. That subsistence lifestyle continues in Kake today. The village’s 500 or so residents, mostly Tlingit, grapple with maintaining traditional values despite being pitched headlong by political forces into a capitalist world. Fish processing and logging are giving way to tourism, as cruise ships visit the picturesque waterfront village. Tourists pour out of the ships, eager to watch traditional Tlingit dancing, nibble specially prepared black seaweed, and take home native art and jars of wildcrafted huckleberry jam.

Photo: one of the world’s largest totem poles (kootéeyaa), 132 feet tall and carved from a single cedar tree, overlooks the village of Kake.

Still, Kake has grappled with an 80 percent unemployment rate, and the issues of drug abuse and domestic violence that accompany economic challenges and a cultural identity strained by generations of pressure from others. Yet residents are resilient, generous, and determined to move forward. And providing the skills and confidence to work, play and travel safely in remote locations, and respond competently in case of emergency, fits perfectly with the tribe’s aims for development. The tribal leadership of Kake welcomed WMA to town.

Outdoor Safety in Southeast Alaska

What are the outdoor hazards in rural Southeast? Commercial fishing is a major activity, and is responsible for many of the area’s injuries and fatalities. It’s the deadliest occupation in the United States, in fact. Alaska commercial fishing fatalities were recorded at 26 times the national average for occupational deaths. Many of those deaths are drownings, from falling overboard, and most who drowned weren’t wearing PFDs. Alcohol is a significant contributing factor.

Logging in Southeast remains significant, and like commercial fishing, has a disproportionately high injury and fatality rate. In fact, logging occupations have the second highest fatality rate in the US, behind fishing. (Neither fishing or logging are positioned for sustained increase, however; tourism is the region’s primary growth industry today.)

All-terrain vehicle use is common for accessing remote areas for work, subsistence activities, or recreation. ATV accidents are a significant mechanism for injury.

Southeast Alaska has both brown bears and black bears. (The term ‘brown bear’ generally refers to brown bears living on the coast—Coastal Brown Bears—; brown bears living inland—Grizzly Bears—; and brown bears living on or near Kodiak Island—Kodiak Brown Bears.)

Bear attacks are rare, however. A 1999 review in the Journal of Wilderness and Environmental Medicine showed one human death a year in North America from bear attack, compared to 67 from dog bites, and 90,000 from homicide. Cardiovascular disease—brought on in part by a sedentary lifestyle and poor diet—kills over 600,000 Americans a year. This has led to the observation that couches and hamburgers are more dangerous than any wildlife.

But many residents of rural Southeast spend substantial time working, hunting, gathering food or medicine, or recreating in the woods or on the water. So trauma, hypothermia, and drowning remain real concerns. And rescue can be days away, particularly if weather prohibits evacuation by air.

Happily, however, Alaska has little in the way of venomous snakes or tropical diseases so common as wilderness mechanisms for injury or illness in more equatorial parts of the world.

Wilderness First Aid, Alaska-Style

Viristar, an outdoor program consultancy that among other services provides wilderness medical training under license from Wilderness Medical Associates, provided the first aid training in Kake.

The Wilderness First Aid course used WMA’s body systems approach. The basic anatomy and physiology of circulatory, respiratory, and other body systems were systematically explored. The pathophysiology of each system was briefly reviewed. And assessment and treatment of the most common problems in each body system were covered through drills and debriefs.

Each body system was reviewed through the lens of the wilderness context: situations of delayed or prolonged transport, improvised equipment, and extreme environments.

An additional day was added on to the standard two-day Wilderness First Aid schedule. This allowed time for some discussion on broader risk management topics. The class discussed prevention, emphasizing that the best accident is the one that never happened. Participants were reminded there’s a limited amount that can be done prehospitally for severe injuries, particularly in remote environments like rural southeast Alaska.

Several of the course participants were teens. Research from functional magnetic resonance imaging shows that the reasoned, cautious part of the brain—the prefrontal cortex—matures only in one’s mid-20’s. However, the limbic system’s amygdala—the brain region that rewards risk-taking—is fully engaged well before then. This is theorized to lead to greater risk-taking in teenagers. The class’ youth participants were encouraged to do their best to moderate their risk-taking, until their brains were more balanced and fully developed.

Rural Alaska has the worst crime statistics in the nation’s Native American communities. Alaska Native communities experience the highest rates of family violence, suicide and alcohol abuse in the United States. The Kake tribal government works hard to address these issues. And the training provided emphasized how alcohol contributes enormously to drowning, motor vehicle accidents, and other causes of outdoor injury and mortality.

The training also discussed outdoor leaders’ legal responsibilities, covering concepts including negligence, consent, abandonment, and documentation.

The Wilderness First Aid class ended with a multi-hour mass casualty incident simulation. The sim was customized for the drowning and ATV injury mechanisms common to the area. This was the participant’s favorite part of the course!

Some students assumed the role of a group of kayakers that was caught by severe weather, capsized, and experienced a drowning. Others acted as a group of ATV riders which passed by the shoreline and encountered the stricken boaters. While racing to go to the rescue, they ran into trouble themselves. The remaining students, acting as rescuers, had to assess a chaotic scene spread over many acres of shoreline and forest, assess patients, treat them, and transport them to safety. As the emergency was wrapping up, one rescuer went down with a simulated sudden asthma attack. But other rescuers jumped on the situation and provided her with the medication and care required.

After days of learning and skill-building, students acted decisively in the face of crisis, efficiently treating and packaging patients, and managing a complex and dynamic emergency scene.

The woods and waters of Southeast now have a new cohort of Alaskans certified in wilderness first aid. They’re trained to respond to the area’s most commonly encountered wilderness medical emergencies.

And they’re more aware of factors that cause outdoor accidents, and how to prevent incidents from occurring in the first place.

Alaska is a place of extraordinary natural beauty. But with wildness comes risk. These new Wilderness Medical Associates graduates are better prepared than before to help others in need—whether it’s a boating accident, ATV crash, or a chainsaw injury on a remote Icy Strait island.

Jeff Baierlein is Director of the outdoor program consultancy Viristar and has instructed WMA-certificated wilderness medicine courses since 1997.

Epilogue

The Next Level of Risk: A Systems Approach

The world is a little safer, with a new cohort of Alaskan wilderness first aiders at the ready. But a systems-thinking approach to wilderness risk management raises another level of questions. These questions go beyond how to assess and treat outdoor incidents. They go deeper than the proximate causes of injury such as alcohol use and lack of PFDs. They look instead at root causes influencing outdoor safety.

What happens to the outdoor risk context in a changing climate? Rural Alaskans travel by ice roads in the winter, but unpredictable warming trends can change ice break-up dates, leading snowmobilers to unexpectedly plunge through the ice.

Changes in rainfall and snowmelt patterns can lead to drought stress and tree mortality, increasing the risk of dangerous wildfires that threaten both lives and property.

Climate change is shrinking fish stocks. This can threaten already precarious rural livelihoods, and the resource-based economies that provide for education, social services, and other functions that foster safe and stable rural communities.

The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 and other laws, which pushed tribal and clan members into unfamiliar corporate structures, left uncompleted the development of economic and cultural sustainability that supports occupational and recreational outdoor safety.

Happily, a constellation of organizations, including tribes and groups like the Sustainable Southeast Partnership, is advancing solutions to these systemic issues. They are working hard to address root causes and underlying systemic risks that affect safety in the outdoors.