On August 8, 2023, the wind was picking up on the beautiful Hawaiian island of Maui. Stormy weather led electrical lines to collapse, and the power went out. Fires ignited, fanned by the wind.

In the island town of Lahaina, smoke appeared. Wind-driven debris was strewn across neighborhoods. As the smoke thickened, embers began flying through the air. It was time to evacuate.

Seven-year-old Tony Takafua jumped in his mom’s small car, along with his mother and grandparents. But a fallen tree blocked access to the main road, and stranded vehicles also obstructed the escape route.

Nearby homes began to burst into flames.

Tony’s uncle Folau, a beloved member of the island’s Polynesian community who greeted travelers at zipline tours, had evacuated earlier in another vehicle with his four children. As the heat inside his big truck grew, with his children screaming and crying, he had rammed his Nissan Titan over the fallen tree and was able to drive to safety.

The next day, Folau returned to his extended family’s neighborhood, a wasteland of homes burned to ashes. He found the charred remains of a vehicle—melted tires, metal frame distorted by the ferocious heat of the wildfire. Three generations of his extended family died in the car.

Tony was the fire’s youngest victim. He had been due to begin second grade the next day.

A Flawed Emergency Response

The Lahaina wildfire, which was only one of multiple wildfires across the island of Maui that day, killed over 100 people. It burned more than 2,200 structures, causing more than USD 5 billion in damage. Six thousand people in Maui were rendered homeless. It was the deadliest American fire in more than a century.

The fire left Lahaina looking like a bombed-out wreck. In the words of one observer, there was “just lifeless, smoky, and sooty devastation where Lahaina town used to be.”

Emergency officials worked hard to respond to the fire, but in the aftermath of the incident, shortcomings in response became clear.

The Lahaina blaze raced across the landscape at speeds up to 100 kilometers per hour—faster than a speeding car, and more quickly than emergency response authorities were prepared to handle.

The 80 emergency warning sirens placed around the region were never sounded to alert residents of the impending flames.

Evacuation routes were congested, blocked by downed power lines, and ineffective.

Officials delayed sending an evacuation alert to mobile phones until fires had already engulfed much of the area. One region never received an evacuation alert.

The Maui Emergency Management Agency did not fully activate its emergency operations center until the fire had charged deep into the town, burning many buildings.

Cellphone service failed.

Many residents had little warning, and struggled to find ways to escape. Victims died inside buildings, in vehicles, and in the ocean, where a number had fled to escape the flames.

Firefighters’ water hydrants ran dry as the water system, stressed by a regional water shortage, collapsed.

Police vehicles lacked breaching kits that could be used to clear roadblocks such as the many fallen trees and power lines that closed off escape routes.

Winds up to 100 kph made it difficult for emergency responders without earpieces to hear radio transmissions once they stepped out of their vehicles.

Emergency responders were forced to improvise. A police officer tied his own straps to a fence and pulled it down with his police vehicle to make an improvised escape route. A firefighter seeking help for an unresponsive co-worker asked to borrow a police officer’s vehicle.

A communications breakdown led the mayor’s office to being unaware of the severity of the fire, and thereby unable to provide adequate emergency leadership.

An incident review by the Maui Police Department (MPD) described many of these findings, and recommended improved training of emergency responders. The review noted “Training for a fire of this magnitude is not what any officer would imagine their training would be used for.” The report recommended Incident Command System training for officers, and training on activation of the police department’s Department Operations Center (DOC). The review specifically recommended that all commanders participate in live training exercises in DOC activation.

The report noted that “in the midst of the chaos created by the fires,” some officers were unable to retrieve or activate their body-worn cameras, and many cameras died as it was “challenging, if not impossible” to recharge them.

The report also recommended installing real-time cameras throughout the region to detect smoke and fire.

Extreme Weather Events From Climate Change

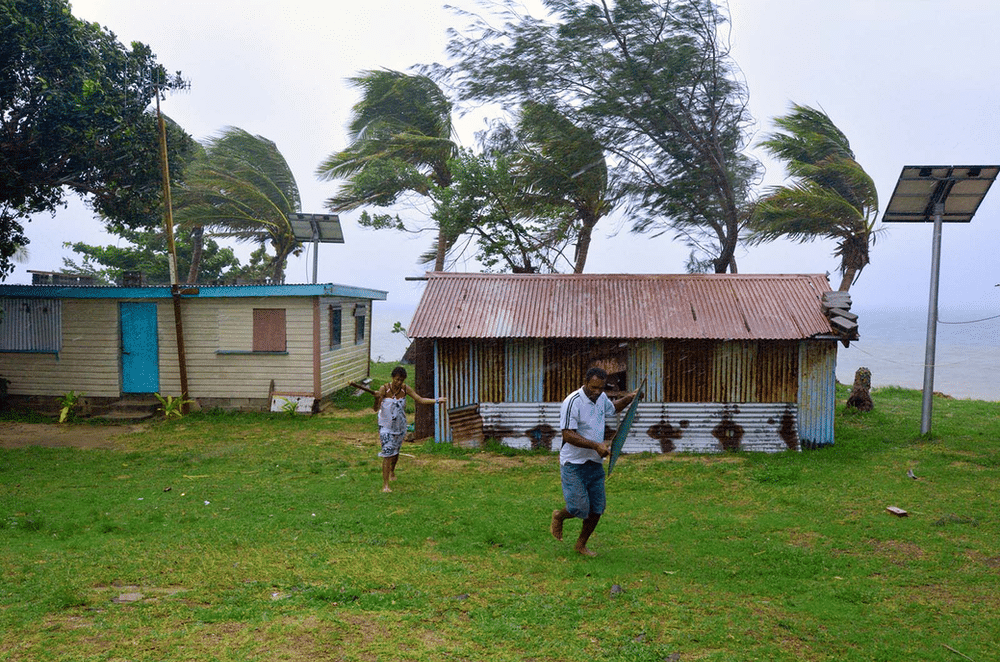

Climate change has made wildfires in Hawaii grow more quickly, as the region gets hotter and drier for parts of the year. The area consumed by wildfires in Hawaii each year has quadrupled in the last few decades.

In Hawaii and around the world, climate change is leading to more powerful, more frequent, and more devastating extreme weather events.

While any single occurrence of a weather-related incident may not be able to be tied directly to the global climate emergency, the clear scientific consensus is that catastrophes like the Lahaina fire will become more common and more severe as climate change, driven by fossil fuel use, continues.

Rapid and unanticipated changes in the global climate may be a factor leading to systemic deficits in preparations to prevent and respond to environmental emergencies.

Hawaii’s 2022 Comprehensive Emergency Management Plan described wildfire risk as a “low” risk to people, despite the dramatic increase in fire size and risk factors such as drought. (Cyber threats were ranked as “high.”)

A Maui County Report from 2021 noted a rapid increase in the size of wildfires, but said that funds to prevent and mitigate fires were inadequate. It said the fire department’s strategic plan “fails to address fire prevention as a mission or goal, a significant oversight.”

Implications for Outdoor and Adventure Safety

A changing climate brought about by human activity influences risk for adventure, travel, experiential, wilderness and outdoor programs in many ways.

Some of these changes are happening quickly, are difficult to precisely anticipate, and are not easy to mitigate. It can be a challenge for organizations to respond rapidly and effectively.

Direct Safety Risks

The global climate crisis creates direct risks for those seeking outdoor and adventure experiences. For example:

Previously dependable water sources in the desert are drying up, posing risks to trekkers.

Rivers now subject to increasingly intense storms are flooding unpredictably, posing risks for paddlers, rafters and other river users.

Extreme heat is increasing risks of fatal heat stroke.

Tick-borne diseases are spreading to new areas, following warmer winters.

Harmful algal blooms can be dangerous, even lethal, to swimmers and others in or near the water.

Outdoor and adventure organizations are seeing their activity areas burn up or flood, leading businesses to limit activities or close down entirely.

Mudslides have inundated outdoor recreation facilities and swept away victims.

Melting glaciers are collapsing on mountaineers and hikers with fatal results.

Increased Risk of Pandemic

Climate change, along with increasing human encroachment into natural areas, is a leading factor in spillover events of viruses from a reservoir such as a wildlife species into humans.

A changing climate forces animals to adjust migration patterns and find new homes. This brings virus reservoirs into closer contact with humans, increasing the risk of disease transmission.

Climate change also damages biodiversity, and with it the ecological balances that mitigate the spread of disease.

The increased probability of epidemics and pandemics wrought by climate change can heighten safety risks for travelers and adventurers. And, as was the case with COVID-19, they pose enterprise-level risk to travel-based and experiential education programs which may have to pause operations, alter itineraries, or shut down entirely.

Harms from Altered Global Governance

Climate change stresses local, regional, and national governments, and destabilizes international governance systems.

This can lead to degradation in the quality of governance, and can increase the risk of harms to millions.

Climate Change Leading to Right-Wing Nationalism Leading to Discrimination and Hate

A increase in climate-related disasters in recent years has coincided with a rise in right-wing nationalism across the world, in places including the USA, Hungary, the UK, Türkiye, Italy, Germany, Brazil and elsewhere.

Research suggests that the socioeconomic stresses brought about by climate change—such as crop failure, flooding, and wildfire—increases a sense of threat in societies, and this may be an element leading to the increase of right-wing nationalism globally.

Researchers say that as cultures feel threatened—by economic changes, ecological catastrophes or other factors—they become more “tight,” or strict, prejudiced and severe. Climate-related incidents have been found to be a predictor of this cultural tightness.

Studies suggest that ecological threats like hurricanes (cyclones/typhoons) and wildfire increase intolerance and prejudice. People who felt most threatened were most likely to vote for right-wing politicians such as Donald Trump and Marine Le Pen.

A Self-Reinforcing Loop

The potential for climate disaster to lead to a rise in authoritarian right-wing political leadership, with its associated xenophobia, homophobia, sexism and racism, may feed on itself.

As far-right nationalist politicians tend to fail to implement solutions to the climate crisis, increasing climate-related harms may perpetuate and reinforce authoritarian systems in a vicious cycle.

Millions of people, mostly in low-income areas of the world, have been displaced from their homes by climate disasters. This causes mass migration. Right-wing politicians seize on this involuntary immigration to promote xenophobic, racist views, and a culture of fear and threat used to help them preserve their grip on power.

The problem of climate change, then, is turned on its head: rather than a cause to build a sustainable global economy and support the world’s most vulnerable, climate catastrophes are used to advance right-wing ideology, protect the powerful, and normalize discrimination against migrants, racial minorities, women, and others.

Harms to the Outdoor Adventure Sector

A rise in nationalism and xenophobia can lead to safety incidents with travelers who face discrimination or attack on the basis of their religion, gender, race, gender identity, sexual orientation, or other characteristics.

And such right-wing, illiberal regimes can harm travel-based and adventure tourism businesses that depend on safe and welcoming destinations with functioning security and public health systems, and which welcome travelers from a wide variety of backgrounds.

Conservative governments which use climate change to incite fear of migrants and promote right-wing policies—the “greening of hate”—typically have an anti-regulatory agenda, which can inhibit common-sense safety regulation that could boost the adventure, travel and outdoor recreation sectors. We may see this in the UK, where the conservative government is considering dismantling the landmark Adventure Activities Licensing Regulations, the first-in-the-world requirements for good adventure safety practice at the national level.

And over time, outdoor and adventure organizations that depend on healthy and well-functioning societies for a sustainable business environment may find that right-wing anti-globalization degrades the health, economic strength and security of societies in nations where these businesses seek customers, or which they use as program destinations.

Improving Safety Outcomes: A Systems Approach

The climate-linked tragedy of the Maui wildfires may have been easy to foresee by some, such as planners at the Hawai’i Emergency Management Agency, leadership at the Hawaii Wildfire Management Organization, climatologists, and the Maui County Commissioners who raised concerns about lack of wildfire prevention planning.

However, it’s clear that local emergency response agencies were not well-prepared for the speed and scale of the August wildfires.

But planning for major incidents is really hard.

Political, cultural, change management, financial, and other challenges make planning for crises difficult.

So does the human tendency to focus on immediate threats, rather than abstract, long-term challenges like climate change.

And preparing for critical incidents—regardless of political will and the availability of resources at hand—is difficult.

This is because, in an understanding of how incidents occur based on complex sociotechnical systems theory, critical incidents typically occur as a result of an unpredictable combination of risk factors, which come together in a way that is impossible to anticipate in advance to lead to a major mishap.

This makes preventing all large-scale catastrophes, all the time, difficult to impossible.

In the aftermath of an incident, recommendations are often made. They sometimes seem obvious in hindsight—but are nowhere near as clear before a crisis occurs.

Who would have thought police cars should be equipped to remove fallen power poles so residents can evacuate from a wildfire?

Who would have anticipated that radio communications would break down due to high winds?

Who would have anticipated the body-worn camera system useful for documenting, analyzing and learning from incidents would fail due to access to recharging facilities?

These issues, which became clear during the incident, were not so evident beforehand to the dedicated, experienced, career-professional emergency managers tasked with wildfire prevention and response.

This is not unexpected, and recognition of this dynamic is part of the science of systems-informed safety.

Even in the best-prepared organizations, the nature of critical incidents is such that they can still find an organization unable to completely prevent their occurrence, or fully mitigate their harms.

The MPD’s after-action review was full of recommendations, from assigning radio ear pieces to officers and improving emergency notification, to improving pay for emergency services communications staff and retrofitting the autopsy suite.

(The report, in recognition of the long-lasting psychological stress injury that crisis survivors may experience, encouraged survivors to consider seeking professional assistance for emotional well-being, and provided a link to grief support services and trauma-informed care.)

The Lahaina wildfire incident recalls another tragedy, where a young person died on a high ropes challenge course in Singapore after slipping off a high element.

Following the incident, some ropes course operators started using body cameras on facilitators to help verify that safety procedures were understood and followed.

This is not a procedure challenge course operators might normally think to employ, in the normal course of business. But in hindsight, this enhanced safety procedure was seen as another layer in the safety system that could help prevent future incidents. It’s an example of the “resilience engineering” approach to safety—incorporating redundancy and extra capacity into a safety system, so that a breakdown in one part of the system doesn’t lead to catastrophic failure of the entire risk management structure.

It’s not always evident in the moment if the safety systems in place at a given time are sufficient, or inadequate, or (as is rarely the case) excessive. Each incident, each tragedy, illuminates a path forward to improve risk management practices, and enhance the quality and sustainability of the work that is done.

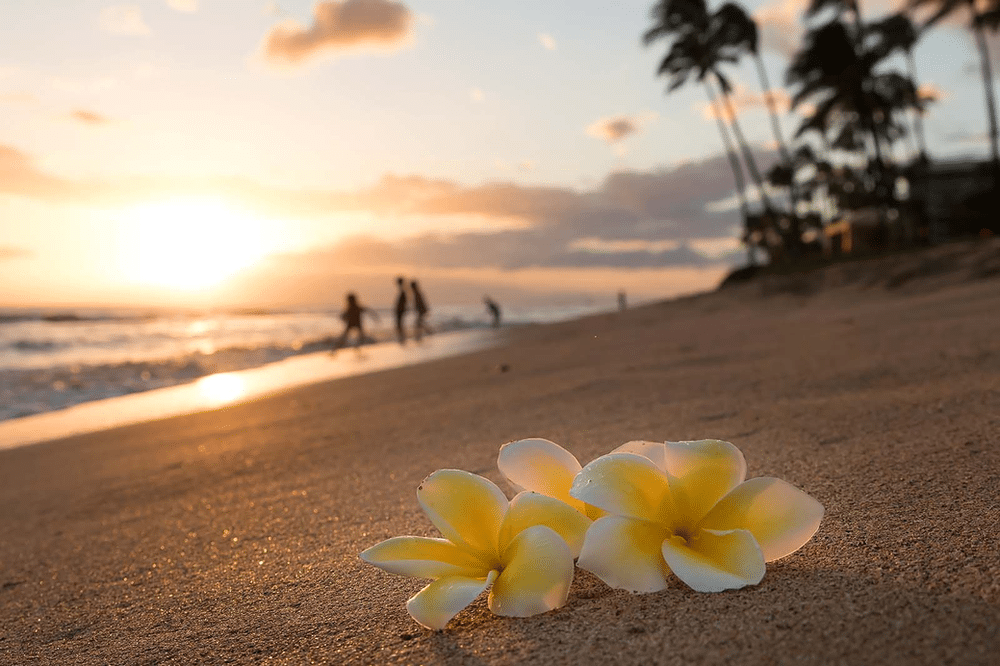

Tony Takafua, seven years old and about to head into second grade, loved spending time at the beach. He and his mom would spend days on Maui’s sandy shores, where he would jump off cliffs. He liked riding bikes around the neighborhood with his cousins. He would dress up in a ta’ovala, his traditional Tongan dress. He raised money for children with heart problems. He basked in the deep love his mother had for him.

The tragedy of Tony’s untimely death—and that of the 100 other victims of the Lahaina wildfire, the deadliest fire in modern American history—is a scar of searing grief and pain that will never completely go away.

But the MPD report—titled “Maui Strong”—acknowledged the great losses of that day, and offered detailed recommendations to help prevent future tragedies.

The report concluded: “Now, here we stand, amid destruction and chaos, with an opportunity to write a new story.”

The review illustrated the resilience of the Maui community—and that in the face of adversity, the spirit of aloha shines bright.

All of us can honor the memory of Tony and the others lost in the Lahaina wildfire by seeking to take whatever steps we can to address the factors—at all levels of the complex system of outdoor and adventure activities—that will improve safety outcomes.

This is a challenging task. But in the words of the MPD report: “‘A‘ohe hana nui ke alu ‘ia”—no task is too big when done together.