Historic Tragedy Bears Relevance Today

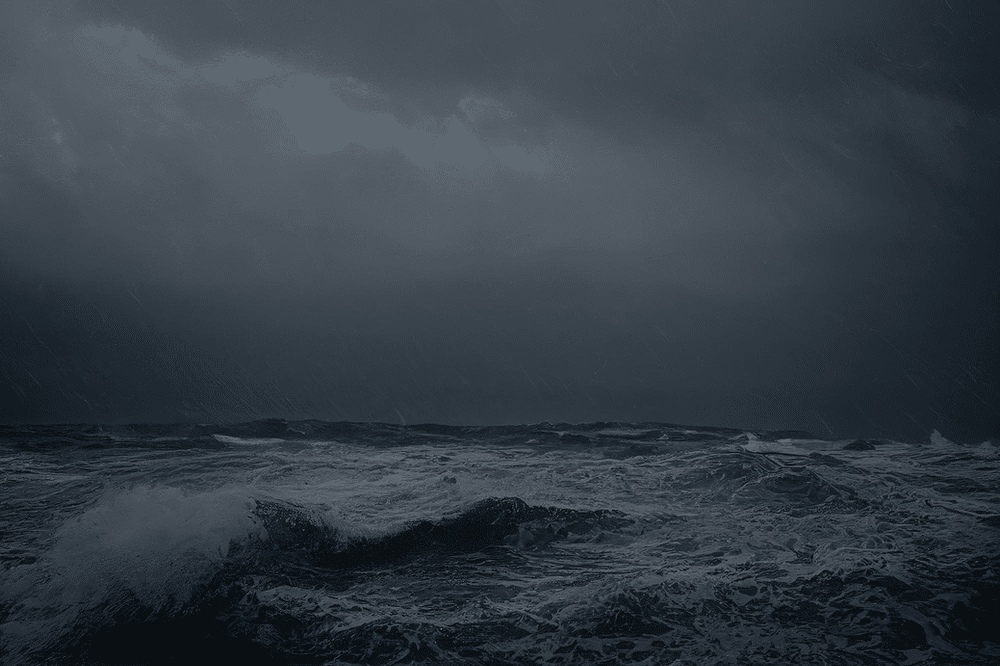

Timothy Breidegam was shaking. He had been floating in the ocean for hours. He was cold, and getting weak. His kayak had capsized in a storm that overcame his group of nine kayakers on a five-day expedition off the coast of Baja California, Mexico. He and five others were clinging to a single kayak, tossed by 4.5-meter (15-foot) high waves in winds up to 48 km per hour (30 miles per hour).

Tim was having a hard time holding on.

When a big wave would swamp them, the kayakers would come up from underwater, spitting out the sea water—until the next wave came and put them underwater again.

Another group member had to shake Tim to get him to spit out the water. He was only occasionally lucid.

The group had been struggling in the stormy weather since the morning. The sun set. In the dark, a wave hit the group. Tim took in a lot of water, but he didn’t spit it out.

Two of Tim’s expedition mates hauled him on top of the kayak, to give him mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. But it wasn’t enough.

They held onto Tim’s body for about an hour. In the dark, in the storm, with no rescue in sight, after waiting, hoping, they let Tim’s body slip quietly into the sea.

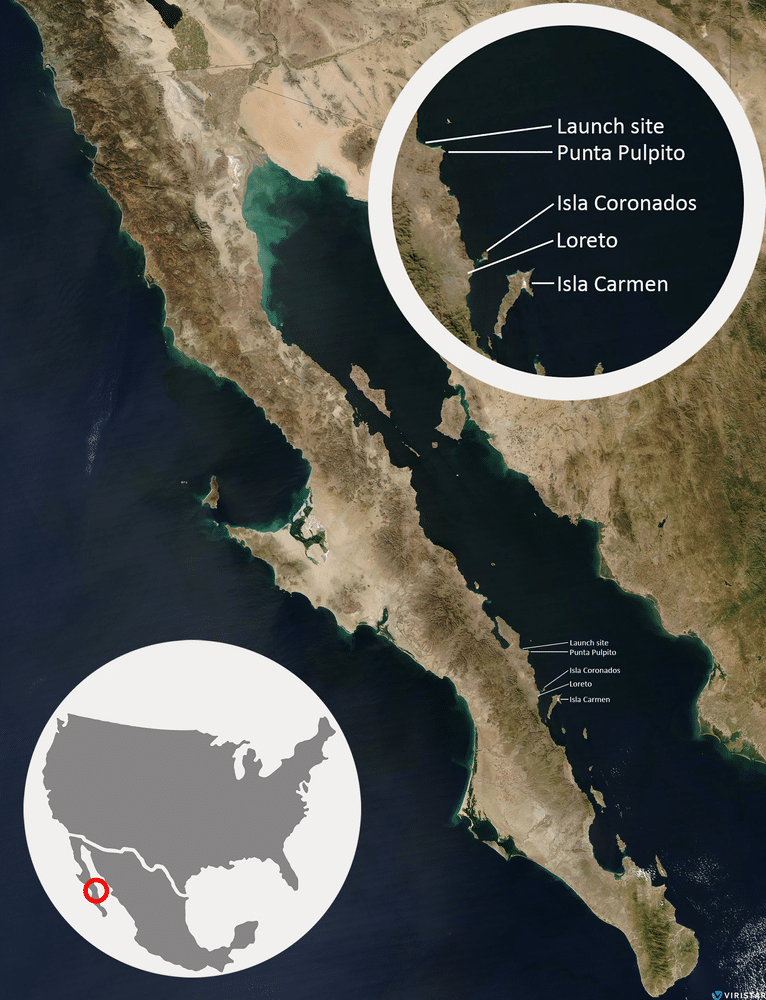

The nine paddlers were students on a wilderness expedition organized by Southwest Outward Bound School, based in Santa Fe, New Mexico USA. They had traveled to Outward Bound’s basecamp in the small coastal community of Loreto, on the eastern shore of Baja California Sur.

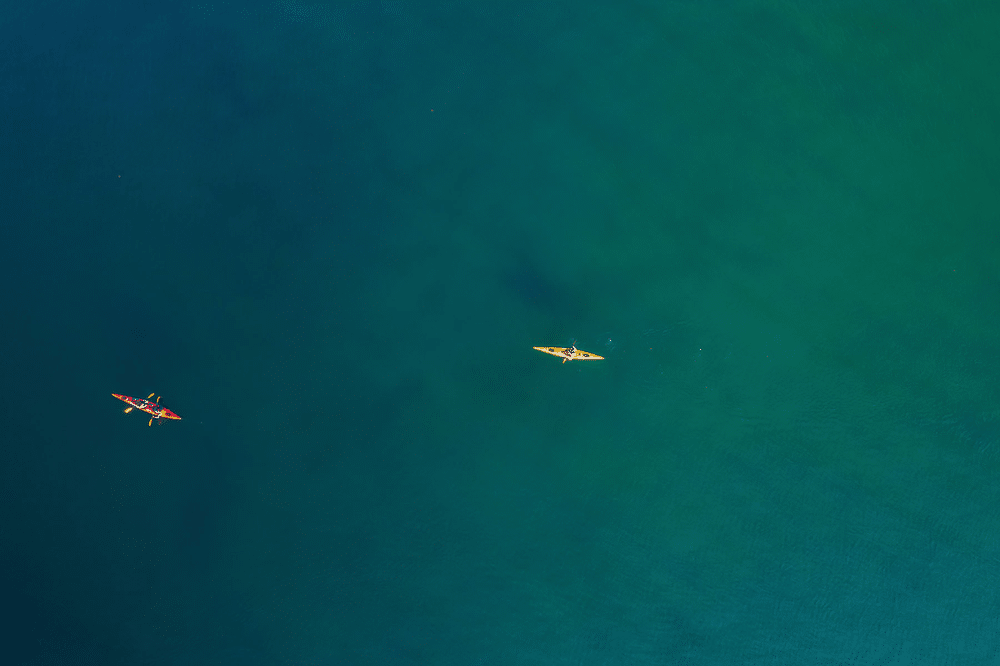

From there the nine students, accompanied by two instructors, began camping in the desert, and snorkeling and fishing in the clear waters of the Gulf of California. Another group of nine students, with two other instructors, was engaged in similar activities nearby.

The students took part in Outward Bound’s traditional three-day “solo,” where each student stayed alone in their own patch of desert. Following Outward Bound tradition, the students all fasted.

After learning outdoor skills from their instructors, and developing as a team, it was then time for the “final expedition,” the most challenging part of the Outward Bound course.

Here both groups of nine students would travel for five days—unaccompanied by their instructors—on a 32-km (20-mile) kayak expedition southward down the coast, to end when the group reached the basecamp in Loreto. Per Outward Bound procedures, their instructors were to check their progress at least every 24 hours. But otherwise they were on their own.

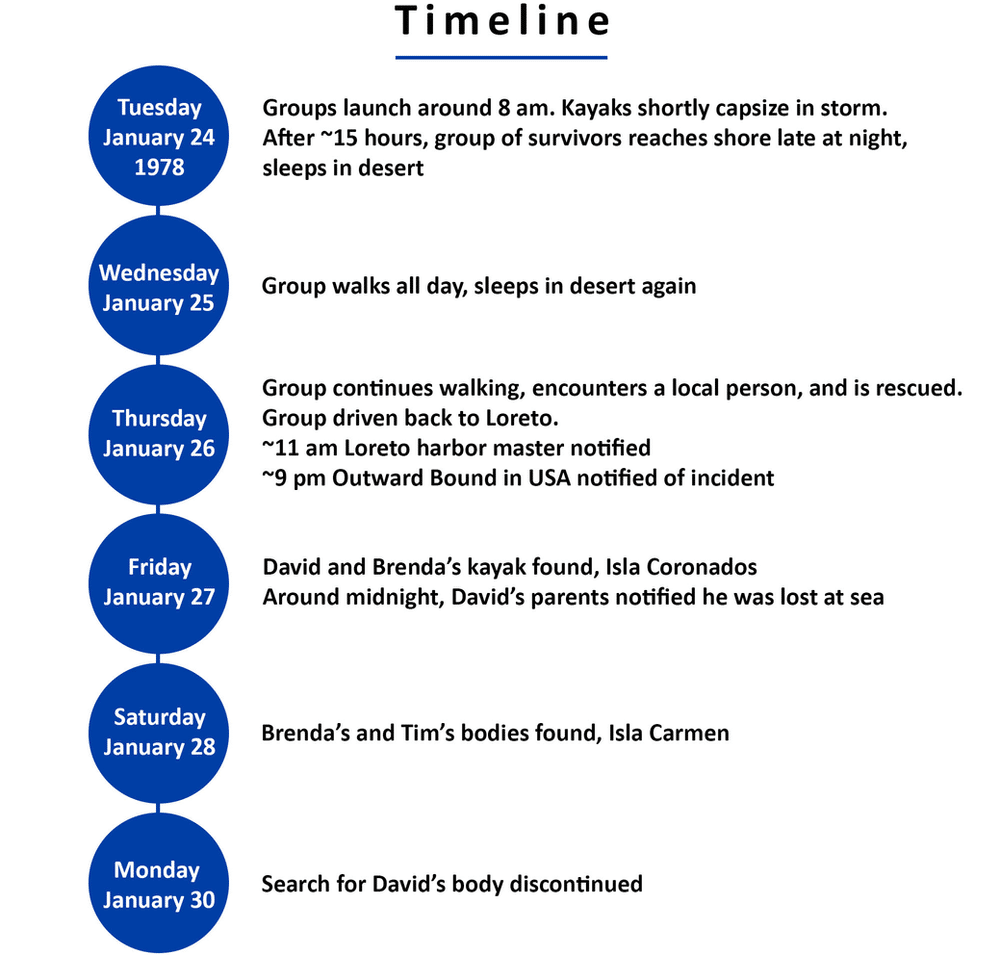

The morning the two groups launched, around 8 am, the sun was shining and the weather was calm—in the words of one of the students, “the water was like glass.” The day was Tuesday, January 24, 1978.

Almost as soon as the students began paddling, the wind picked up, and the water became choppy. Within 20 minutes of starting, one group turned back to shore, concerned for their safety amidst the increasingly rough waves.

But Tim’s group carried on. They were in three tandem kayaks and three singles.

After about 45 minutes of paddling, with weather conditions deteriorating, the group came together to talk about what to do. They decided to head to shore, and made the decision to paddle around an upcoming promontory, Punta Pulpito, figuring they could then seek shelter in a protected bay where there was a sandy beach on which to safely land.

But the wind was increasing, and the waves were getting larger. The tandem kayak which 21-year-old Tim and his paddle partner Catherine were in capsized. The group tried to raft up all the kayaks together and help Tim and Catherine get back into their boat. But a powerful wave crashed into the group, and propelled the kayakers apart, splintering the team.

A single kayak, paddled by Jana Ankrum, was swept away from the main group. A tandem kayak with two students, 18-year-old David Schwimmer and 19-year-old Brenda Herman, also became separated from the others.

Students yelled to Jana, David and Brenda to get to shore, find the instructors, and ask them to bring their motorized boat out to rescue them.

Jana Ankrum was able to reach dry land. David Schwimmer and Brenda Herman disappeared, and everybody assumed they had self-rescued too.

David Reed and BeeBee Foster were able to stay upright in their tandem boat, but all the other kayaks were swept away or sank. The four remaining students—Tim, Catherine Mouseley, Keith Trider and DelRene Davis—clung to the side of David and BeeBee’s boat. The group began paddling and kicking towards shore.

Hours passed as the group struggled in the churning waves. “You lost all sense of time,” Keith later said. “You were just constantly kicking.”

The group debated leaving the sole remaining kayak and attempting to swim for shore, but decided to stick with the boat.

After some 15 grueling hours of hanging on to the boat, and kicking for shore, and after letting go of Tim’s body, the group of five students reached land. Exhausted and traumatized, they pulled a single, drenched, sleeping bag from the kayak and huddled under it for warmth.

As the sun rose over the stark and remote Sonoran desert landscape, the group got up, clambered up a steep cliff-like slope, some 60 meters (200 feet) high, and began to walk. They trudged through the desert all day, aching, hungry, dehydrated, looking for help.

They didn’t find it.

That night, Wednesday, January 25, they located a small low area and tried to get some sleep. The next morning, they got up again, and continued their trek.

Later that day, the group of students spied what they were searching for: a person, in this case a local fisher in his boat not far from shore. Waving the lone sleeping bag they were carrying, they got his attention, and he took them to another fisher’s camp. They were able to get a ride from the camp to Loreto.

It was now Thursday, January 26.

The harbor master in Loreto was notified around 11 am that morning about the missing students.

It wasn’t until about 9 pm that night that Southwest Outward Bound in Santa Fe learned about the incident.

The Coast Guard began a search for the missing students.

On Friday, January 27, Brenda and David’s kayak was sighted on the shore of Isla Coronados.

On Saturday, the 28th, the bodies of Brenda Herman and Tim Breidegam were recovered from nearby Isla Carmen.

The Coast Guard located an intact PFD (life jacket) on Isla Carmen, assumed to be from David Schwimmer.

On Monday, January 30, the Coast Guard suspended its search.

David Schwimmer’s body has never been found.

The other group of nine expedition members, which had returned to shore after 20 minutes of paddling into increasingly stormy weather, had contacted their instructors. The instructors then reportedly traveled in their motorized boat through the same area where Tim and his group were struggling with the wind and waves, but allegedly did not look for the group.

Parents of the students who drowned had many questions. Why weren’t the kayaks fitted with dedicated flotation devices? Why were the groups traveling without radios or emergency flares? Why didn’t the instructors check on the paddle group as the storm moved in? Why, if instructors were supposed to check on their groups every 24 hours, was this not done?

Outward Bound promised answers. The organization, which holds as its creed “above all, compassion,” was considerate and thoughtful. The Chair of the Board visited parents to express condolences in person. The school said it would supply the statements made by instructors and incident survivors.

But the information never arrived. Outward Bound’s insurer told the school not to release any information to family members of those who had died.

The grief parents felt morphed into anger. Stonewalled by Outward Bound, they started their own research. They discovered that students endured a 15-hour nightmare hanging on to a kayak, with no apparent attempt to check on them or initiate a rescue. They learned that students were encouraged to fast during the three-day solo, possibly weakening students’ strength right before the final expedition.

Outward Bound never wrote a letter to the parents of David Schimmer saying they were sorry their child had died. They did send a letter, however, implying his body was likely eaten by sharks.

In an effort to learn the facts of the case, the parents of Timothy Breidegam and David Schwimmer filed a $2 million lawsuit against Southwest Outward Bound.

The suit alleged the Southwest Outward Bound School was negligent, and failed to provide adequate leadership, safety procedures, training, skills, equipment, weather information, supervision or rescue aid to the students in their care.

Leadership of Outward Bound empathized with the need of the parents to understand what happened to their children, who left for a wilderness adventure never to return. And they felt they could not escape the restrictive requirements of their insurer.

Recognizing this difficult conflict, an Outward Bound official acknowledged that ideally they would have been able to sit down with family members and share what they knew—”in a human way, instead of having to go through lawyers.” Speaking of one of the plaintiffs, the official said, “We have forced Mr. Schwimmer to go to court to find out how his son died…and I think that’s reprehensible.”

The case was settled out of court for $200,000, two years later.

A lawsuit over the death of Brenda Herman—who was remembered by her former roommate as “a kind, sweet, compassionate human being”—was also settled out of court.

Improvements in Outdoor Adventure Safety

Immediately following the incident, Outward Bound in the USA made significant changes in its safety procedures and staff structure.

The seven Outward Bound schools in the USA system at the time also soon began coordinating their incident reporting systems so that accurate safety statistics across the national system could be compiled.

And schools enhanced their procedures around informed consent, including making clear the risks of its wilderness expeditions. The organization edited their promotional content, and created a risk disclosure form participants (and the guardians or parents of minor participants) sign.

Following those changes right after the Baja incident, Outward Bound in the USA continued to improve its safety practices. Fasting was discouraged on solos. Field telecommunications were vastly improved. Instructors consistently conducted checks of students at least daily. Practices for checking weather forecasts improved. And training and emergency procedures continued to develop.

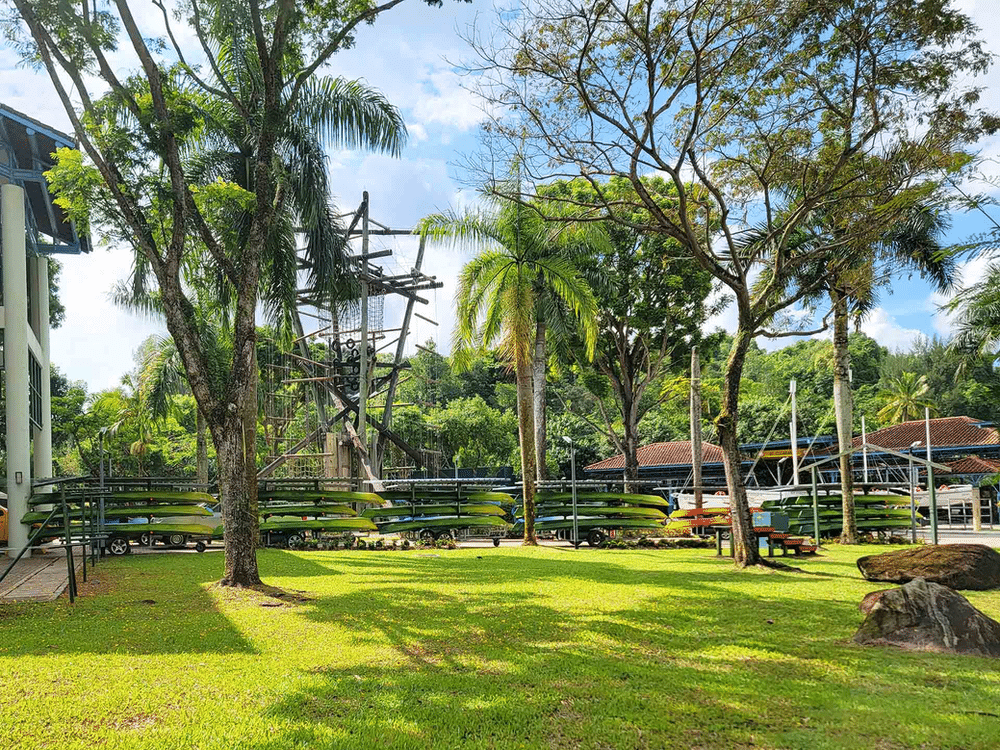

Outward Bound schools in other countries also put in place highly developed safety systems. Outward Bound Singapore has an elaborate risk management system, with extensive activity leader training, a conservative safety culture, thorough safety documents, a screen-filled control room, a fully staffed clinic with attached helipad, and more. Outward Bound Oman has invested heavily in quality and safety, with generous support of the government of Oman, which in 2023 instituted a comprehensive, nation-wide adventure safety licensing process including a third-party audit.

(Disclosure: Viristar staff have previously been employed by Outward Bound, and Viristar provides consulting and training services to Outward Bound schools around the world.)

In the nearly 50 years since the Baja tragedy, risk management in the outdoor adventure industry worldwide has greatly advanced. Sector-wide sharing of incident analyses, published consensus safety standards, well-developed wilderness medicine and other outdoor safety certifications, and organizational accreditation have all been established.

However, friction between insurers who wish to keep incident details confidential, and outdoor organizations who see the benefits in discussing and sharing those details, continues.

Circles of Pain

One of the things that some may not anticipate is the pain, and grief, that can radiate out from a tragedy, and which can influence everyone from survivors and next of kin to those less directly connected to the incident. This hurt, or what specialists might call psychological stress injury, can be unexpectedly long-lasting and severe.

Veronica Schwimmer and her husband received a midnight phone call from Outward Bound, advising them that their son David had been lost at sea. She recounted the numbness she felt in the initial months after his death, and then an enduring mental fog. “For almost a year afterwards I’d just sort of walk around and pick up something and start doing it, and just couldn’t seem to finish things,” she said.

“I know logically and rationally that David is gone—but there’s always this thing. He was never found. I’ll see someone running, or the doorbell will ring…there’s always this glimmer of hope.”

Making Meaning of a Tragedy

This pain can ruin a person, make them bitter.

Deb Ajango, an outdoor safety expert experienced in working with parents of those hurt or killed during adventure activities, recalls one parent she engaged with who was consumed by enduring anger at the organization where their child encountered tragedy during an outdoor event. “They may die a bitter person,” she said.

One of the things that can help people who have suffered a profound loss—such as the untimely death of their child—experience a sense of closure, is to find a way to make meaning from the incident.

In 2014, Mark and Ellen Newman lost their teenage son Ariel on a two-day outdoor education hiking trip in Israel, where on the second day he collapsed in the heat, and died of heat stroke.

The Newmans poured their energies into educating others about heat safety, and how to minimize risks while hiking in the heat. The couple created Ariel’s Checklist, a set of safety guidelines for hiking in the desert, and put together other outdoor safety resources. In this way, they were able to focus on positive movement forward, honor their son’s memory, and help ensure that his death was not in vain.

The parents of Timothy Breidegam, who perished on the 1978 Outward Bound trip, were determined to honor his legacy. In memory of their son, they established the Timothy M. Breidegam Scholarship Fund at Moravian University, where Tim was in his last semester when he enrolled at Outward Bound. They also created the Timothy M. Breidegam Memorial Faculty & Administrator Service Award at the university in honor of their son’s commitment to service, endowed the Timothy M. Breidegam Fieldhouse, and established the Timothy M. Breidegam Track.

Timothy’s father, who owned a successful manufacturing business, also established the Timothy M. Breidegam Center at the Lutheran Home in Topton, Pennsylvania, and endowed the Timothy M. Breidegam Chair in Neurology at the Lehigh Valley Fleming Neuroscience Institute at Lehigh Valley Health Network.

George Schwimmer, whose son David died alongside Tim, wrote a book, The Search for David, about his attempts to uncover the details of his child’s death, and who David had been in life, in his journey to find closure.

And he pledged to use any proceeds from his lawsuit against Outward Bound for scholarships and further efforts at safety reform, including—recognizing the absence of any federal law in the USA licensing outdoor schools or summer camps—supporting camp safety legislation.

Moving Forward

Not long after the triple drowning in Baja, the Southwest Outward Bound School shut down for good.

The organization had been a successor to the Texas Outward Bound School, which itself closed permanently following the August 11, 1974 death by drowning of 21-year-old Pamela Wells, when her Outward Bound group was caught by a flash flood while camping in Arroyo Segundo, in the Fresno Creek area in southwest Texas.

Today, Outward Bound—with extensive safety policies, and a clear dedication to excellence in risk management—operates at numerous sites in Mexico and around the world. Outward Bound, and other outdoor adventure and experiential education organizations, have in the last half-century made major improvements in safety management—some advances springing from a spirit of proactive innovation, others catalyzed by crisis.

In hindsight, it’s easy to look back and find fault with what, informed by knowledge of when things went terribly wrong, appear to be clear faults in safety culture, judgment, or operational practices.

However, it’s entirely possible for organizations to sincerely believe they are doing the right thing, and prudently taking all the appropriate precautions against reasonably foreseeable harms—and yet, an incident occurs.

Such is the sometimes unfortunate nature of progress: that we learn that what we thought was sufficient, in hindsight appears to no longer be so—but this awareness at times only becomes clear from bitter experience.

Notwithstanding this truth, there is the moral obligation for all of us in the outdoor, travel, experiential and adventure sectors to take the initiative to ask of ourselves: how can we do better? How can we improve the resilience of our incident prevention measures, the quality of our safety culture, the effectiveness of our risk management procedures?

In this way, it is not just grieving parents—or others directly impacted by the events that unfolded as a kayak expedition paddling the sparkling waters of the Gulf of California encountered a January 1978 storm—but it is all of us, who can help ensure that the lives that ended in that tragedy were not lost in vain.