Insurer Requires Association of Canadian Mountain Guides to End Incident Reporting and Learning System

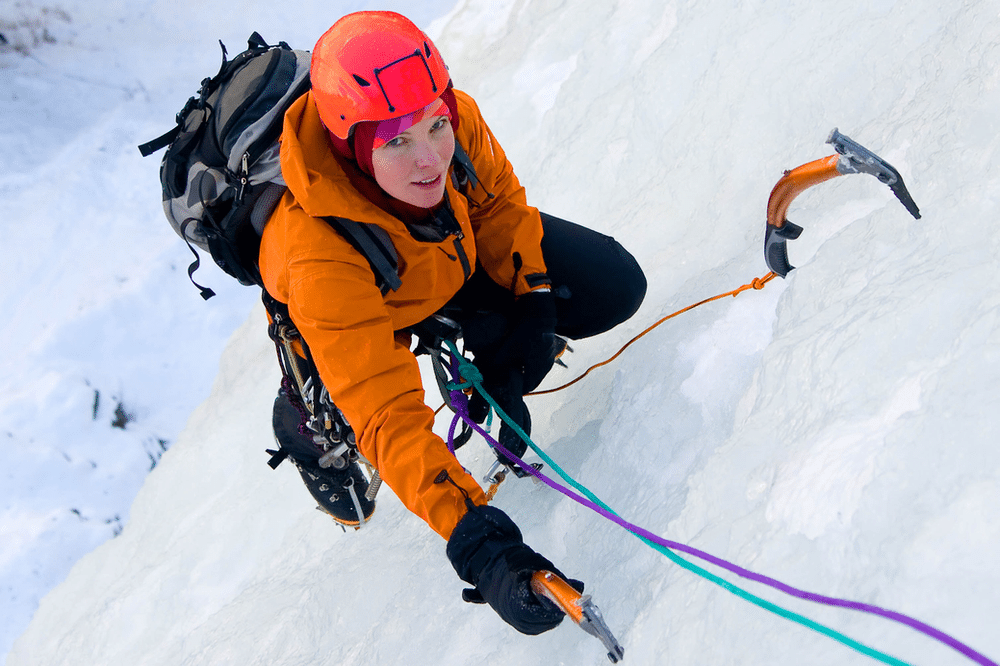

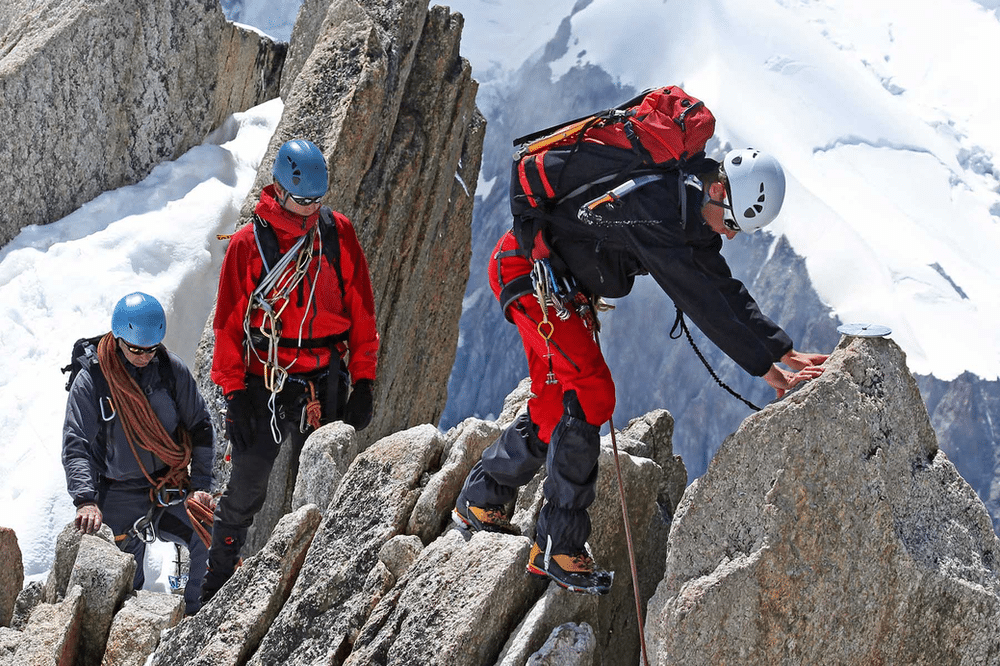

The scenic and jagged peaks of Canada’s mountain ranges offer spectacular adventures to mountaineers. But steep and icy slopes, loose rocks and extreme environments carry risks.

To help alpinists learn from the safety mishaps of others, the Association of Canadian Mountain Guides (ACMG) convened an Incident Review and Learning Committee in 2016, and charged the group with recommending a system for learning from incidents, which would disseminate anonymous incident reports and avoid punitive outcomes of sharing safety mishap details.

Using the committee’s research, the Association established an “Incident Reporting and Learning System,” or IRLS. The system involved submitting anonymous reports through a Google Forms platform. The form had sections to describe the details of the incident and list potential contributing factors.

In 2023, a report of a serious incident was submitted into the IRLS. The seriousness of the incident and the lack of anonymity of the report led to it not being made available through the IRLS. But ACMG procedures permitted such a report to be made. When a lawsuit following the incident was filed, the report, which was not protected by attorney-client privilege, was considered discoverable, and therefore able to be used as evidence against the ACMG.

Concerned that other submitted incident reports could increase their liability, the Association’s insurer asked that the ACMG cease accepting reports into the Incident Reporting and Learning System, and discontinue the system entirely.

The ACMG reluctantly complied, shutting down the IRLS and dissolving the committee that led to its formation.

The mountaineering community recognizes that sharing stories of alpine mishaps is a powerful way to improve safety outcomes in the mountains. The sudden demise of the mountain guide association’s structure for doing so came as a shock and a disappointment.

(Disclosure: Viristar personnel have been involved in the evaluation of Canadian mountaineering and climbing incidents as incident reviewer and expert witness; these incidents may have directly influenced the status of incident reporting in Canadian mountaineering.)

The termination of the incident reporting system created uncertainty about what information can be shared with whom. Can a member of the ACMG share incident details with other mountain guides, or members of the expedition where the incident occurred? If the practice of a mountain guide’s organization is to submit avalanche incidents to the Canadian Avalanche Association’s well-respected InfoEx database, will the ACMG—who provides liability insurance coverage to many mountain guiding operations in Canada—permit this?

These questions are still unsettled. In an article in the winter 2024 edition of The Arête, the ACMG’s magazine, a mountain guide and former chair of the now-defunct Incident Review and Learning Committee concluded: “You should not talk to colleagues, your clients (even if they were involved), or anyone else.” They feel the only allowed incident reporting is what is legally required, such as to occupational health and safety authorities.

The author noted that the ACMG, which trains mountain guides across Canada, can be sued in an incident where there is an allegation that inadequate training contributed to the mishap. Consequently, the Association has an interest in ensuring potentially damaging details contained in an incident report are not released.

The lack of an incident reporting system, the author continued, “I would argue is unethical.” Reporting, discussing, and learning from incidents, they argue, “would lead to fewer guides and clients getting injured or killed,” and the lack of a system puts guides and clients at greater risk.

The author noted that the mental health of guides, too, is better served when they can process critical incidents with colleagues and with clients who were involved in an incident but survived.

Factors Influencing Sector-Wide Incident Reporting

In some sectors, there are legal protections for talking about an incident with others, such as apology legislation in Alberta Canada which specifies that apologies are not an admission of fault or guilt. Apology law is specifically designed to prevent litigation, recognizing that many people sue simply to gain information, and that apologies can reduce the emotional charge that often leads to a lawsuit. Research has found that full disclosure practices can lead to significant savings in litigation-related costs.

For example, following the death of their son in a kayaking incident in Baja California, Mexico, where the trip organizers originally promised to disclose details but then reneged, citing insurance company restrictions, George and Veronica Schwimmer joined a $2 million lawsuit against the expedition provider, seeing it as the only way to get the incident reports and statements from the drowning. Recognizing this unfortunate situation, a representative of the outdoor organization said, “Like it or not…by our actions, we have forced Mr. Schwimmer to go to court to find out how his son died.”

However, legal protections for discussing an incident do not apply globally, and lawyers and insurers continue to discourage information-sharing.

In other situations, such as following investigations by government authorities, incident reports are made public. However, in some cases, such as with reports from the UK’s Marine Accident Investigation Branch, by law these reports are inadmissible in lawsuits seeking to attribute blame.

The absence of clear legal protections for reporting safety incidents in mountaineering—or other outdoor recreation or adventure tourism activities—inhibits the establishment of systems for collecting and learning from incident reports, and the healing and closure that can come when survivors discuss and process a major crisis.

Workload issues, with busy adventure operators unable to find time to submit detailed reports, are another obstacle to sector-wide incident report collection systems. This was an issue with the ACMG structure, and was also cited by a group in the UK seeking to establish a process, similar to the ACMG’s Incident Reporting and Learning System, for gathering and disseminating incident reports from outdoor adventure activities.

Initiatives such as Australia’s well-regarded UPLOADS Project, which gathers incident reports and publishes authoritative summaries of incidents in Australia’s led outdoor activity sector, are wise to take into account these factors in their work to ensure the sustainability of their incident reporting and learning projects.

Gathering incident reports from outdoor, experiential and adventure activities, and sharing anonymized summaries and analyses of these reports, can help improve quality and safety. And freely discussing mishaps is important in mitigating psychological stress injury as well.

For the benefit of outdoor and adventure operators, industry associations, and activity leaders, and the clients they serve, finding a pathway to support reporting and discussing safety incidents is a goal worth continuing to pursue.