“Avoidable” Paddleboarding Tragedy in Wales Leads to Calls for Regulators and Peak Bodies to Act

It was a bright autumn day, with a light westerly breeze, and about 11°C—seemingly a great day for a stand up paddleboard trip down the Western Cleddau river. The group of nine SUPers set out for a day of adventure and fun on the estuarine river, which winds through scenic Welsh countryside before emptying into the Irish Sea.

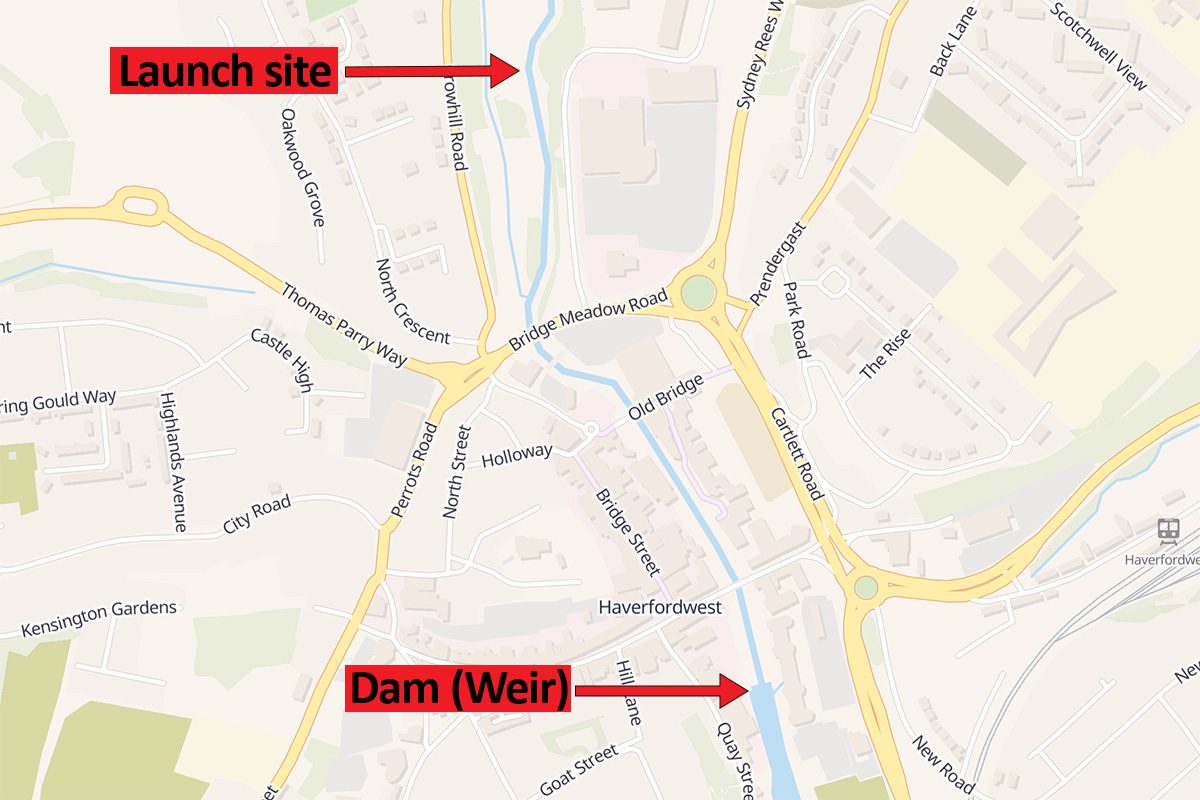

The paddlers put in at the small town of Haverfordwest in southwest Wales, with plans to float some 18 kilometers down to the Jolly Sailor pub in the village of Burton Ferry.

The group launched and began paddling downstream, through the center of town. After having paddled just some 750 meters, the group encountered a low head dam, or weir, with a drop of approximately 1.2 meters. The paddlers went over the dam, some being caught in the recirculating water just below.

Four individuals—three trip participants and one of the trip leaders—drowned.

The trip was a commercial tour organized by a newly established local SUP tour company, which had been offering tours since the summer.

The tour leaders were experienced paddleboarders. The company owner and tour leader was a volunteer with the Royal National Lifeboat Institution (a marine rescue charity), and led a cold water swimming group. Her co-leader was a keen surfer and former Army surf champion. Both had completed SUP Safety & Rescue and SUP Foundation Instructor courses from the Water Skills Academy.

The company owner and her co-leader had completed a reconnaissance trip of the river two months earlier, which included an inspection of the low head dam. They had a backup plan in case of inclement weather: a walking tour of the area. Participants had been told to bring walking gear so they would be ready to participate in the alternate experience. Participants had also been instructed to bring an SUP with leash and paddle, buoyancy aid (PFD), wetsuit and waterproof jacket for the river trip.

At 6:00 am the day of the trip, October 30, 2021, the trip leaders evaluated the weather, and decided the conditions—low wind and no rain—allowed the tour to proceed.

The group boarded the van used for the trip and drove to Haverfordwest. In town, the leaders got out of the van and inspected the river, which had a calm and glassy appearance, and found it to be suitable. The group launched their paddleboards and headed downstream.

About nine minutes later, they had all gone over the dam.

What Caused The Incident?

What led to this terrible tragedy?

The UK Department for Transport’s Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) conducted an investigation.

MAIB investigations are focused on preventing future incidents—not determining liability or assigning blame. Like Coroner’s reports in Australia, they take a wide look at contributing factors.

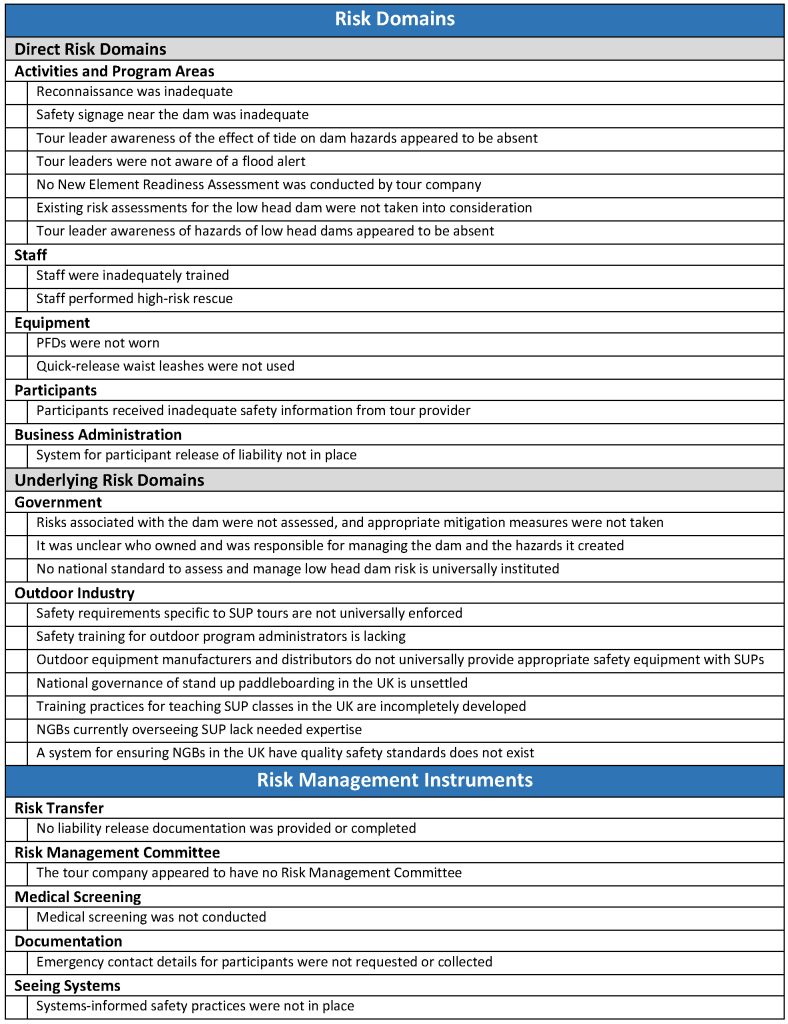

MAIB’s report identified a great number of contributing factors. These included problems related to managing risks in the activity area, risks related to tour leaders and participants, and equipment-related risks. The report identified shortcomings with government and outdoor industry bodies. And issues with risk transfer, medical screening and documentation were noted.

We’ll use a model of incident causation to help us look at these causal elements, and how they combined to lead to the incident.

Without a unified model of the factors that lead to incidents, risk management efforts may be fragmentary and ineffective, addressing apparent deficiencies as they come to attention, but never implementing a comprehensive structure to reduce all potential risks to an acceptably low level.

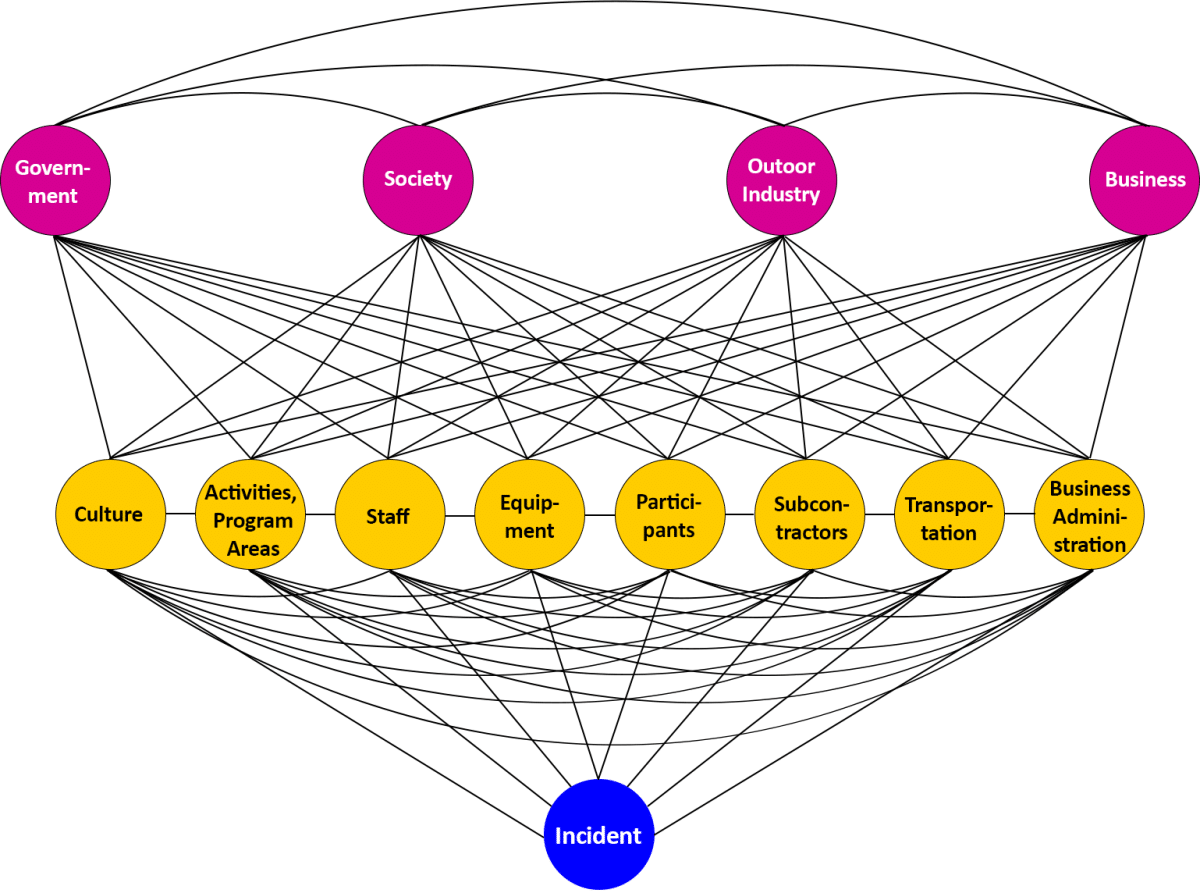

The Risk Domains model below shows how risks in direct risk domains such as staff and equipment can lead to an incident.

Issues in underlying risk domains such as government and the outdoor industry can contribute indirectly to causing an incident.

In any outdoor organization, specific risks existing in these risk domains should be identified, and then reduced so far as is reasonably practicable.

In addition, certain broad-based tools, or risk management instruments, can be applied to reduce risks across many or all risk domains at once.

Analysis of the incident showed specific issues that existed in a number of direct risk domains and underlying risk domains.

Analysis also illustrated how shortcomings in applying a number of risk management instruments caused problems.

Many of these issues were explicitly described in the MAIB report; others were implicit in the report’s content.

A chart of analysis findings regarding the incident at the low head dam on the Western Cleddau is below. Following that are more detailed explanations of each issue.

Risk Domains

Direct Risk Domains

- Activities and Program Areas

- Reconnaissance was inadequate

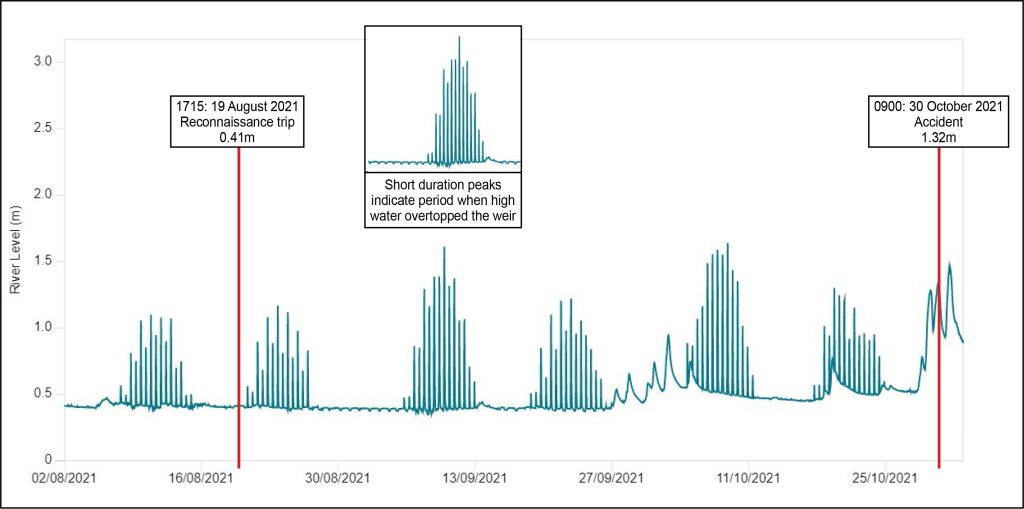

The tour organizers completed a reconnaissance trip of the paddling route in August 2021. At that time, the river at the area around the dam was running at a relatively low volume, and had almost no current.

And because the dam is so close to where the river empties into the ocean, at high tide the dam may be completely underwater. At the time of the recce (recon), the dam was largely submerged, with little drop, or difference in the water level above and below the dam. The river surface was glassy and still.

The morning of the tour, the trip leaders again checked the condition of the river, just downstream of the launch site. But they did not visit the dam. The tour leaders were unaware of the changed tidal conditions, which led to a 1.2 meter drop at the dam on the day of the trip.

And the river gauge just upstream of the dam, which showed the river level at 0.41 meters on the day of the recce, indicated a river level of 1.32 meters on the day of the incident.

Despite the presence of fast-flowing, mud-laden water, the tour leaders were unaware of the high river level.

In addition, a sign close to the group’s launch site warned that the dam was dangerous; it advised river users to exit the river and carry their craft around the weir. The tour leaders did not heed the sign.

- Safety signage near the dam was inadequate

At the point where the group accessed the river, four signs provided important safety information. One informed river users of a dangerous dam that should be portaged on river left. A second displayed a map of the weir location. A third sign warned of dangerous currents. And a post with faded text indicated the weir location.

The tour leaders and participants either did not see or did not pay attention to the signs.

The signage, however, did not follow British and international consensus standards for water safety signs.

The relevant standards are 1) BS ISO 20712:2008, Water safety signs and beach safety flags – Specifications for water safety signs used in workplaces and public areas, and 2) BS ISO 3864-1 Graphical symbols. Safety colours and safety signs. Design principles for safety signs and safety markings.

The standards call for high impact, recognizable signage that does not rely on the written word.

Signage also used the term “portage” to signify carrying around the dam. Canoers and kayakers may be familiar with this term, but it is not commonly used by paddleboarders.

The report found that if signage standards had been followed, “it is highly likely” that the tour leaders would have been aware the dam was dangerous, and may not have led group members over it and directly into the recirculating hydraulic below, causing their deaths.

- Tour leader awareness of the effect of tide on dam hazards appeared to be absent

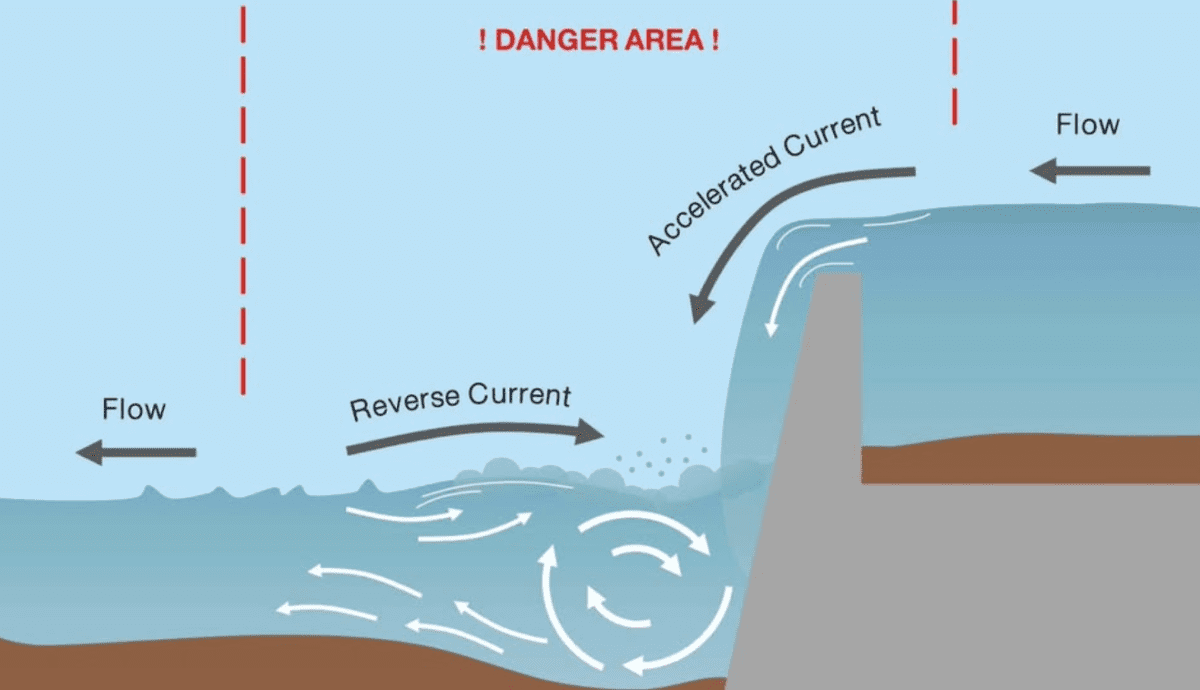

At high tides (such as the time around when the initial reconnaissance was done), water from downstream can flood over the dam and increase the river level above the dam. However, at lower tides (such as around when the group paddled over the dam), a significant drop and resulting hydraulic towback, with the potential to trap paddlers, can appear.

There were no indications that the trip leaders, through in-person reconnaissance or other research, were aware of the implications of the height of the tide on the level of danger posed by the dam.

The low tide on the morning of the incident, coupled with high river level and fast current, led to a recirculating flow of water below the weir powerful enough to trap paddlers and paddleboards against the base of the dam, from which there was no means of escape.

- Tour leaders were not aware of a flood alert

Cyfoeth Naturiol Cymru Natural Resources Wales publishes flood warnings and alerts for rivers throughout Wales. At 1645 on October 28, the regulatory body issued a flood alert for the Western Cleddau. At 1045 on October 29, the alert was updated. This alert was in force at the time of the incident.

Knowledge that the flood alert had been issued could have led the tour leaders to take additional precautions. The tour leaders, however, were unaware of the flood alert.

- No New Element Readiness Assessment was conducted by tour company

No formal and comprehensive assessment of the risks associated with operating paddleboarding trips on the Western Cleddau appears to have been completed by the paddleboarding company.

The organization, which was just over a year old and which had started offering paddleboarding trips earlier in the year, had run commercial tours in the River Thames and River Wye, but never on the Western Cleddau.

When an outdoor program anticipates encountering novel circumstances—such as a new participant population, a new program location, a new program activity, or a change in circumstance (such as a pandemic), it’s good practice to formally assess the risks inherent in the new situation.

In the UK and in other current or recently former parts of the British Commonwealth, a probabilistic risk assessment (PRA), or risk matrix, is commonly used to this end. (These are less regularly used by outdoor programs in other locations, such as the USA.)

The creation of a written risk assessment document was not legally required of the tour provider, as UK regulations require this only for organizations with five or more employees.

Nevertheless, it’s reasonable to anticipate that the discipline brought about by creating a documented risk assessment spreadsheet when considering opening up operations on the Western Cleddau for the first time might have led to a better understanding of the risks of low head dams and, in particular, risks associated with the dam on the Western Cleddau.

- Existing risk assessments for the low head dam were not taken into consideration

Risk assessments of the Western Cleddau were published online by the Haverfordwest Kayak Club (HKC), but there was no indication that the tour company was aware of them, and the tour company did not follow the risk assessment guidance.

HKC’s risk assessments recommended that all weirs should be visually checked and dynamically assessed before being descended. They specifically stated that, with respect to the Haverfordwest (or ‘town’) weir, that that the area around weir “should not normally be used,” and that “at high water levels the town weir becomes extremely dangerous with high potential for loss of life.”

The risk assessment noted that the launch site above the weir may be used when the water level is low (gauge reading 0.62 meters), but that “Two coaches should be present, one to supervise launching, the other to guard the weir.”

At the time of the incident, the gauge reading was 1.32 meters.

- Tour leader awareness of hazards of low head dams appeared to be absent

Low head dams, or weirs, are notorious for posing a danger to boaters and others who encounter the recirculating water at their base. Their unique geometry can create backflow currents and turbulence that are practically inescapable for even the strongest PFD-clad swimmer. This is true even in situations without the flood and tidal characteristics of the Haverfordwest dam.

They are known around the world as “drowning machines.”

The MAIB report found that there were no indications that the trip leaders were aware of the scale of the hazard posed by the low head dam.

- Staff

- Staff were inadequately trained

The tour leaders were experienced paddleboarders. They had paddled 100 miles in 24 hours on the River Wye, and one had organized and led SUP events as charity fundraisers.

They both had also completed a one-day SUP Safety & Rescue and a two-day SUP Foundation Instructor course led by an experienced instructor from the UK-based Water Skills Academy.

These trainings took place in benign conditions, and included instruction techniques for working with beginners and novice paddleboarders in sheltered waters and bays, and on flat waters, small lakes, and slow-moving rivers.

The training did not qualify trainees to lead tours on fast-flowing rivers. It was not intended to qualify individuals to organize and run expeditions, or to operate on hazardous river settings. The training syllabi did not cover the hazard posed by low head dams.

(The Water Skills Academy has been offering a five-day Expedition SUP Guide Training & Assessment course since around 2016. The expedition course includes “all aspects required to lead SUP clients in remote, wilderness environments during multi day journeys.”)

The MAIB report concluded that the trip leaders did not have the training to recognize a dangerous weir, and that they were not qualified to lead tours or expeditions.

- Staff performed high-risk rescue

One of the tour leaders was at the back of the group as it approached the dam. He could see that something was wrong, and pulled up on shore to evaluate the situation from land, where he saw participants were having difficulty.

The leader jumped into the river above the dam with his SUP, and was carried over the right side of the dam. He became entrapped in the recirculating hydraulic and drowned.

Attempting an in-person water rescue is the most high-risk of water rescue options.

Groups involved in water safety, from the Red Cross to the US military, use the “Reach, Throw, Don’t Go, Call for Help” sequence of water rescue options, in descending order of priority.

(Decades previously, options included “Reach, Throw, Go.” The “Go” option was deemphasized due to the extreme risks of close-at-hand rescues by lay personnel.)

One the left hand side of the dam were two lifebuoy rings with throw lines, which could have been used by the trip leader in lieu of the much more hazardous option of entering the water.

- Equipment

- PFDs were not worn

Both trip leaders and one participant did not wear a PFD (personal flotation device, buoyancy aid) as they went over the low head dam.

This is contrary to best practice, which is to use a PFD while on fast-flowing water. It was also contrary to the recommendations in the Water Skills Academy Safety and Rescue Guide, which recommended use of PFDs on rivers.

(There is some complexity to the issue of PFDs in self-rescue from recirculating currents, where one rescue approach is to attempt to dive to the bottom of the hydraulic boil and swim or crawl downstream, an approach made more difficult if wearing a high-buoyancy PFD.)

- Quick-release waist leashes were not used

No members of the group wore quick-release waist leashes attached to their SUP.

Instead, eight wore an ankle leash, and one person did not use a leash.

This is contrary to standard practice, which is that paddleboarders on fast-flowing water should use a quick release waist leash. Quick-release leashes are helpful when it is important to be able to separate oneself from the paddleboard.

The trip leaders were taught this during their SUP training—and were required, on occasion, to wear them during their training course.

The Water Skills Academy SUP Safety and Rescue Guide advised that, except for sheltered water settings, the leash should be attached to a quick-release system, so the paddler can release the board if it becomes entrapped.

The trip leaders, however, did not follow that practice, nor did they require trip participants to do so.

One of the participants caught in the recirculating water at the base of the low head dam repeatedly drifted downriver without their SUP, but they were pulled back towards the dam.

This was likely because the SUP, attached to them by the ankle, was trapped at the dam either by recirculating water or debris.

Consequently, even though the participant was repeatedly being washed downstream, they were unable to escape from the recirculating hydraulic.

If they had been wearing a quick-release waist leash, they might have been able to separate themselves from their SUP and swim to safety.

- Participants

- Participants received inadequate safety information from tour provider

Participants were not briefed on the presence of the low head dam, and were unaware that they would be descending the dam.

They were not briefed on how to descend it.

Participants were unaware that the leaders’ intention was that the participants would descend the dam, but that if they were uncomfortable paddling over the dam, they would land above the dam and carry their paddleboard around it.

All participants followed the leader over the dam.

- Business Administration

- System for participant release of liability not in place

The organization did not have a system where it asked participants to acknowledge and accept the risks of participating in the trip, and release the organization from liability.

This is an essential part of any outdoor program provider’s administrative risk management structure. However, participants for this trip were not given the opportunity to provide informed consent, nor were they required to complete a legal disclaimer.

Underlying Risk Domains

- Government

- Risks associated with the dam were not assessed, and appropriate mitigation measures were not taken

Low head dams are well-known for the hazards they pose. There are established principles for evaluating the specific risks that any particular dam holds, and how they should be mitigated.

However, no risk assessment of the Haverfordwest dam was ever apparently conducted. And there was no evidence that appropriate risk mitigation measures were ever put into place.

Why did this not occur?

Who is In Charge?

No governmental agency or other authority said that the dam was theirs.

When the Marine Accident Investigation Branch began their investigation into the incident, they tried to figure out who owned and was responsible for the dam.

Ownership of the dam, which was built in 1966 by the local authority, appeared to been transferred “between a number of agencies/authorities” since its initial construction.

“Enquiries by the MAIB prompted correspondence between the relevant local authorities,” the investigators wrote. Eventually, “it was agreed that Dŵr Cymru Welsh Water (DCWW) owned the weir.”

But that didn’t settle the issue of who was responsible overall for safety at the dam.

It was also eventually established that although DCWW owned the dam, the land on either side of it (where safety ingress/egress points and self-rescue structures might be located) was under the jurisdiction of the county and the Pembrokeshire County Council. Milford Haven Port Authority (MHPA) managed navigation on the tidal water up to the southern face of the dam. And the Environment Agency had done work on the ramp-like fish pass in the middle of the dam, including efforts to make the dam less dangerous.

The Glandŵr Cymru Canal and River Trust, meanwhile, had created a process to manage low head dam risk, according to the MAIB. And safety signs had been installed by the Bridge Meadow Trust, in collaboration with the Haverfordwest Kayak Club, the Welsh Council for Voluntary Action, and others.

The Risk Assessment System

The weir risk assessment tool, created by Cyfoeth Naturiol Cymru Natural Resources Wales/Rescue 3 Europe, is a well-developed rubric for evaluating risks of low head dams, each of which may have its own design and hydrological characteristics.

Yet with a hodgepodge of agencies involved in managing dam-associated risks—and none of them, initially, accepting responsibility for the dam itself—it’s not surprising that the industry-leading risk assessment was not completed for the Haverfordwest weir.

Reducing Recirculating Hydraulic Risk

In 2003, the Environment Agency, an environmental protection entity in the UK, replaced the fish pass (a ramp by which fish can ascend up the dam).

During the replacement process, British Canoeing (then Canoe England) proposed inserting ‘fillet’ stone structures at various points below the dam to weaken hydraulic forces and create flush points to wash anyone trapped below the dam downstream.

These were inserted in 2003, but no flush points were observed at the weir the day after the incident. No apparent steps were taken after installation to see if the structures met their intended aims, and to ensure that they did so.

The MAIB report stated that if the desired flush points had been created, they might have allowed paddleboarders trapped below the dam to escape.

Escape from the Side

If it’s not possible to escape the dam by getting downstream, sometimes one can self-rescue by traveling to the side.

However, at the Haverfordwest weir, the banks on either side of the below-dam hydraulic were closed, vertical surfaces. A 1.5 meter wall on the right hand side and an approximately 0.9 meter surface on the left-hand side of the weir had been built. No steps or ladders were available.

This, the report noted, meant that “there was no means of escape from the water for someone trapped at the weir; and, that it would be very difficult for others to rescue them.”

The MAIB’s report described how the four paddleboarders who lost their lives almost certainly did so because they became trapped in recirculating waters below the dam. “Once trapped in these hydraulic forces,” the report continued, “the closed-ended nature of the weir meant that, without steps or a ladder, it was impossible for them to escape from the water and access for potential rescuers was challenging.”

- It was unclear who owned and was responsible for managing the dam and the hazards it created

Risks associated with the dam were not assessed, and appropriate mitigation measures were not taken. A contributing factor, as discussed above, was that no agency initially took responsibility for the dam, and for ensuring that relevant safety measures were in place.

Follow-up actions, however, had been conducted. The month following the incident, MAIB recommended to Dŵr Cymru Welsh Water that they conduct a risk assessment on the dam and implement appropriate mitigation measures, such as “riverside signage, warning marker buoys and, if deemed necessary, physical barriers.” The risk assessment began in August, 2022.

MAIB also recommended to other local government entities that they go through the same process for any low head dams for which they are responsible.

- No national standard to assess and manage low head dam risk is universally instituted

The MAIB report noted that there was no national standard to assess and manage risk at low head dams. An alphabet soup of agencies is responsible for managing the Haverfordwest dam and its immediate surroundings. And weir safety standards appear to be voluntary, rather than a compulsory regulatory requirement.

However, entities such as the Construction Industry Research and Information Association, Cyfoeth Naturiol Cymru Natural Resources Wales and Rescue 3 Europe have well-developed low head dam safety information, and following the Haverfordwest tragedy, the UK government has taken steps to help ensure that risk management at low head dams is improved.

- Outdoor Industry

The sport of stand up paddleboarding is growing rapidly in the UK. A 2019 survey found SUP I the fastest-growing UK water sport, with participation growing by over 285 percent between 2015 and 2019.

The industry is struggling to keep up.

- Safety requirements specific to SUP tours are not universally enforced

UK law requires that employers ensure the health and safety of employees and anyone else who may be affected by their operation, so far as reasonably practicable.

But besides that, for adventure activity providers serving adults, following widely accepted good practice specific to SUP appears to be optional.

The UK has Adventure Activities Licensing Regulations, under the Activity Centres (Young Persons’ Safety) Act.

The regulations cover caving, climbing, trekking, and watersports.

Watersports includes “most activities involving unpowered craft” such as “canoeing, rafting, sailing and related activities.” The regulations specifically cover watersports on tidal reaches of rivers, sea lochs, and “any inland waters where the surface is turbulent because of weirs.”

Although stand up paddleboards are not mentioned, craft subject to licensing include “canoes, kayaks or similar craft, and rafts (inflatable, improvised, rigid, etc.).”

The regulations require risk assessments and mitigation measures, persons competent to advise on safety matters, competent instructors, safety briefings, and more. Providers must pass a third-party audit before being licensed.

But the regulations only apply to commercial providers of activities to young people under the age of 18.

Accreditation: optional

The organization that led the Western Cleddau river trip applied to become an affiliated member of the Welsh Surfing Federation (WSF).

The WSF replied, noting that in order for the application to be accepted, the provider would need to show a certificate of liability insurance, risk assessments, standard operating procedures, an emergency action plan, and copies of current coaching qualifications and rescue certifications (awards) for the instructors.

The tour company did not provide these items. The application was not approved.

Less than three weeks later, the tour group paddled over the dam.

- Safety training for outdoor program administrators is lacking

Much outdoor adventure safety training is developed for, and provided to, those who directly lead the activity with participants.

Fewer well-developed resources are available to those responsible for administering adventure programs, and designing the safety infrastructure under which the individual trip and activity leaders operate.

However, much of good risk management—writing standard operating procedures, fostering a positive safety culture, drafting and updating an emergency action plan, and so on—is administrative in nature.

The activity leaders themselves—such as instructors, guides, coaches, facilitators, or tour leaders—have little influence over these managerial aspects of risk management, which are highly influential in supporting good safety outcomes.

The MAIB report found that the SUP Foundation Instructors course that the company owner (and trip co-leader) took was not intended to be used by candidates to organise and run expeditions.

Although accreditation and licensing schemes can define good practice for an outdoor adventure company, the development and widespread adoption of training opportunities for managers might increase safety performance by outdoor and adventure activity provider organizations.

- Outdoor equipment manufacturers and distributors do not universally provide appropriate safety equipment with SUPs

MAIB’s report noted that SUPs sold in the UK typically come with ankle leashes, which connect the paddleboard to the user’s lower leg or ankle with a hook-and-loop (Velcro) fastener. Owners can therefore be unaware that a quick release waist leash is generally recommended when paddling on fast-flowing water with snag or entrapment risks.

A number of outdoor activity bodies provide detailed guidance on which type of leash and release system is appropriate for particular environments.

Manufacturers and distributors of SUPs could provide detailed guidance about leash and release system recommendations, and make suitable merchandise appropriately accessible at point of sale.

- National governance of stand up paddleboarding in the UK is unsettled

The MAIB report found issues with the governance of stand up paddleboarding in the UK. These included:

- Who is a National Governing Body (NGB) for SUP in the UK is unsettled

- NGBs are not required, as a condition of recognition, to have well-developed safety standards

- No unified SUP safety standards exist

- NGBs did not keep up with evolution in SUP

As a result, it is difficult for a prospective customer—or anyone else—to judge the competency of an SUP activity provider.

The status of who is an NGB for SUP is unsettled.

Which organization governs the sport of stand up paddleboarding in the UK? It’s not always clear.

In 2008, the International Surfing Association (ISA) recognized SUP as a discipline of surfing. This meant that the Welsh and Irish Surfing Federations, already acknowledged as surfing NGBs, now were governing bodies for SUP.

However, there was contention. In 2020, the International Court of Arbitration in Sport determined that ISA would be in charge of SUP in the Olympics, but that ISA and the International Canoe Federation could both hold official SUP competitions.

In 2022, British Canoeing, Canoe Wales, the Scottish Canoe Association, and the Canoe Association of Northern Ireland applied to be recognised as NGBs for SUP. At the time of MAIB’s investigation, the Sports Councils responsible for recognition had not yet rendered decisions.

NGBs are not required, as a condition of being recognized, to have systems or processes for safety in their sport.

Recognition as an official National Governing Body for a sport in the UK is given by a national Sports Council. These are Sports Wales, Sport Northern Ireland, sportscotland and Sport England, empowered by royal charter to support sport in their respective nation.

The recognized NGB is then responsible for governance of their sport.

A recognized NGB, according to the Sports Councils’ Recognition Policy, “should demonstrate it has taken measures to minimise and control risk to participants and has in place appropriate policies to manage the risk.”

However, the Sports Council does not have regulatory powers. Recognition by a Sports Council does not mean that it has approved an NGB’s safety systems or processes.

The question then arises, who is responsible for ensuring that NGBs have well-developed safety requirements for practitioners of their sport? In the words of the first-century Roman poet Juvenal, quis custodiet ipsos custodes? Who will guard the guards themselves?

The answer, it appears, may be nobody.

Unified SUP safety standards were absent.

The report found that at the time of the incident, the UK’s surf federations had not mutually agreed upon instructional standards for SUP training. They had not issued joint safety guidance on topics such as quick-release leash belts and PFD use.

The report concluded, “Without an active national governing body for the sport of stand up paddleboarding in the UK, there is no consistent safety messaging to the sport’s participants on stand up paddleboard safety in respect of potential risks from weirs and other hazards, or on the wearing of appropriate safety equipment.”

NGBs did not keep up with evolution in SUP.

The modern sport of stand up paddleboarding originated in the coastal surfing environment, although SUP traces its roots back thousands of years.

From the surf zone, SUP then rapidly expanded in recent years to flatwater lakes, rivers, and the open sea.

Surfing federations held SUP in their remit once the International Surfing Association recognized SUP as a discipline of surfing.

But MAIB found that “while the existing surf NGBs had a good understanding of the surf zone where their primary discipline was taking place, they did not all have the expertise to advise on the risks of operating SUPs in other areas, such as rivers.”

Conclusion

The unsettled nature of governance of stand up paddleboarding in the UK created ambiguity and an absence of accountability for safety management within the sport.

MAIB’s report noted this made it hard for the clients who signed up for the tour on the Western Cleddau to judge if the company organizing the tour adhered to good safety practice and employed competent trip leaders.

The report concluded: “Without an active national governing body for the sport of stand up paddleboarding in the UK there is no metric for those who seek to participate in a sport in an environment where there are multiple unregulated training providers, with inconsistent governance, to judge the competence of those businesses offering stand up paddleboard training, tours or expeditions.”

- Training practices for teaching SUP classes in the UK are incompletely developed

Established water sports in the UK, such as sailing and canoeing, have nationally recognized instructional standards. These standards specify that training courses must be run by qualified instructors associated with the relevant National Governing Body. The courses must be run within the NGB’s framework in association with a training centre recognized by the NGB.

While the Royal Yachting Association and British Canoeing have nationally recognized training schemes with well-developed standards for instructors and training centres, MAIB found that the same is not true for the sport of stand up paddleboarding.

SUP instructors can operate independently of an NGB-approved training centre, and multiple providers worked under a structure of inconsistent governance.

This makes it difficult for the competence of a SUP company or its activity leaders to be evaluated, so that unqualified operators can be avoided.

- NGBs currently overseeing SUP lack needed expertise

Existing surf NGBs had a good understanding of the surf zone, where surfing and other activities were taking place. But, the report noted, “they did not all have the expertise to advise on the risks of operating SUPs in other areas, such as rivers.”

MAIB recommended that Sports Councils “urgently ensure that the recognised national governing body(ies) have the resource, support and expertise to issue advice and guidance, including appropriate training standards to control risk.”

- A system for ensuring NGBs in the UK have quality safety standards does not exist

In the UK, Sports Councils for the nations that comprise the UK recognize National Governing Bodies for different activities, such as SUP, canoeing, and sailing.

Those NGBs are not required, as a condition of recognition, to demonstrate that their safety management systems are comprehensive or appropriate.

Although a prospective NGB has to take “measures to minimise and control risk,” there is no requirement that these be comprehensive and effective, and there is no audit process to evaluate whether that is the case.

MAIB stated that “the safety of participants in some sports lacks any consistent system of oversight.”

MAIB’s report said that “providing it is practically possible,” “effective monitoring” of the standards NGBs establish would be beneficial.

MAIB recommended that national Sports Councils review and develop their criteria for recognizing NGBs to include “the management of safety and adherence to good practice by the governing body and any organisation or companies it accredits.”

The Tragic Case of Morgan Rogers

Morgan Rogers was 24 years old, and the eighth paddleboarder to descend the dam. She lived in Merthyr Tydfil, in South Wales. Her family described her as a “beautiful, kind and loving soul.”

She had been a young firefighter with South Wales Fire and Rescue Service, and had gone on to become a junior firefighter instructor.

Morgan was in training to become a full-time firefighter, with a view to joining a water rescue station in Wales. She was interested in becoming a Royal National Lifeboat Institution crew member.

She was a strong swimmer, and had paddleboard experience on the sea and canals.

Morgan had been awarded British Canoeing Paddlesport Performance 1 and 2 Star certificates. And she attained a Business and Technology Education Council (BTEC) Level 3 National Diploma in Sport (Outdoor Adventure) in 2017.

The Level 3 National Diploma in Sport (Outdoor Adventure) is an extensive and in-depth course covering personal skills development in outdoor activities, health and safety factors in outdoor learning, and outdoor activity provision. It is designed as a training for professional outdoor activities instructors.

The National Diploma includes 720 guided learning hours, and the total qualification time is 975 hours.

How could someone with such extensive skills training and background, in the first nine minutes of a paddleboarding trip, descend a dam, and perish as a result?

What is it about the system of skills training, assessment, outdoor safety standards, and governance of the outdoor adventure sector in the UK—a country with some of the world’s best outdoor adventure safety legislation, and an extremely extensive array of outdoor-adventure-based national governing bodies—that could fail to protect a person from such a tragic result?

“Morgan Rogers was the best that she could be,” her family said.

Andrew Moll, MAIB’s Chief Inspector of Marine Accidents, stated: “This was a tragic and avoidable accident.”

One can hope that the systemic opportunities for improvement the MAIB report described will help prevent future needless and tragic deaths.

Risk Management Instruments

- Risk Transfer

No liability release documentation was provided or completed

Participants were not required to complete a legal disclaimer prior to joining the trip.

Failure to obtain informed consent to risks and some form of liability release invites unwanted and unnecessary liability onto the company providing outdoor experiences.

- Risk Management Committee

The tour company appeared to have no Risk Management Committee

Risk Management Committees typically include representatives external to the company, and provide external viewpoints and guidance. No evidence of such a group supporting safety decisions of the SUP trip organizer was immediately evident.

In the UK, “technical advisors” are sometimes brought on, in lieu of a formal risk management committee. Technical advisors are typically experts in the activities the provider offers (in this case, stand up paddleboarding).

A risk management committee, in contrast, may have specialists who have expertise in insurance, law, general outdoor safety standards, and more. Such a group may systematically review incident reports, conduct research when requested by the organization, or provide feedback on proposed new policies or business activities (such as opening operations in a foreign country), which may represent a scope greater than that of a technical advisor.

In any case, based on the information in MAIB’s report, neither a risk management committee or any technical advisors appeared to be providing guidance to the SUP tour provider.

- Medical Screening

Medical screening was not conducted

Participants were not required to complete medical declarations at any point prior to the trip (or at any other time).

Medical screening helps ensure that participants (and staff) are well-matched to the program activity.

It can be useful for staff to know that an individual has diabetes, for example, or takes medication that prevents blood clotting. This information can inform medical care if there is an emergency.

An individual with a serious medical condition such as an uncontrolled seizure disorder might be screened out of certain SUP activities, for example in settings where rescue may be delayed or prolonged, in order to help ensure an adequate level of safety.

- Documentation

Emergency contact details for participants were not requested or collected

Participants were not required to provide emergency contact details before starting the tour.

This may not have had an immediate impact on the physical well-being of trip participants, but it can affect family members or others.

The lack of emergency contact details delayed the police contacting the families of those who had died.

- Seeing Systems

Systems-informed safety practices were not in place

The most current understanding of incident causation informs us that major incidents often occur when a number of risk factors in multiple risk domains combine in ways we can’t predict in advance, and at a time and in a specific manner we can’t anticipate beforehand.

Led outdoor activities exist in a complex system of people and things—a ‘complex sociotechnical system.’

We therefore need to create robust safety structures that can withstand unpredictable failures within that complex system, without leading to a catastrophic collapse of the entire risk management structure.

To do this, outdoor and experiential organizations can build in extra safety capacity, incorporate redundancy in safety structures, employ an ‘integrated safety culture’ that balances written procedures with individual judgment, and take into account risks in all risk domains and all applicable risk management instruments.

From the information in the MAIB report, it appeared that the SUP tour provider did not have such a systems-informed risk management structure. (Nor is there evidence that the safety trainings and standards easily available to company personnel were well-equipped to help the provider create such a structure.)

One of the tenets of systems-informed safety thinking is to not reflexively blame the person closest to the incident when a mishap occurs. The idea of ‘Just Culture’ suggests that when a major incident happens, investigators instead look for the underlying issues that led to the occurrence. (Potential breaches of law, however, should still be investigated, and intentional misconduct not tolerated.)

Although the SUP operator may not have taken a systems-informed approach to risk management, the MAIB investigators—who considered influences from government, NGBs and other sources—did take this more comprehensive approach.

Analysis

When an incident occurs, it’s important to see it from a systems perspective, and MAIB did a good job of this. Investigators looked at factors from multiple components of the complex system in which the incident occurred—from government entities and sport associations to training providers and others—that led to what they called a preventable accident.

This doesn’t take away the loss. But it helps us understand the underlying causes that led to the tragedy, and better equips us to prevent future incidents.

The Health and Safety Executive, the UK’s workplace safety regulator, also took action. The HSE issued an ‘Immediate Prohibition Notice’ shutting down the provider’s SUP business.

The trip organizer was reportedly arrested by police, on suspicion of gross negligence manslaughter, and then released under investigation.

It’s appropriate to investigate when health and safety laws may have been breached. But the science of incident causation informs us that in many major incidents, multiple factors at many levels of the entire system are involved.

Finding fault with an individual player, while a feature of the judicial system, is less effective at preventing recurrence than actions where all involved parties—from government, to industry associations, to individual providers—take steps to enact effective, enduring change. MAIB’s thoughtful report helps show a way in which this can be done.

One might presume that the company owner and trip leadership of the Western Cleddau tour had the best of intentions, genuinely wanted to provide positive and successful SUP experiences for customers, and did not intentionally put anyone in harm’s way. One tour leader, in fact, lost his life while trying to save the lives of trip participants.

With a systems-informed perspective, we can both hold individuals accountable for legal breaches while attending to the systemic conditions—involving regulators, governing bodies, equipment manufacturers, and others—that must be addressed if tragedies like the incident at the Haverfordwest weir are to be prevented in the future.

Even though government regulation of adventure activities, when well-designed and enforced, has the potential to be extremely effective, loopholes prevented the UK’s outdoor adventure safety law from influencing this case. Loopholes, however, are common in outdoor safety regulation in countries around the world, from India to New Zealand and Switzerland.

The United Kingdom deserves credit for establishing a world-leading system for outdoor safety, involving legislation, an enormous assortment of outdoor/sport NGBs, and standardized training like the National Diploma in Sport (Outdoor Adventure) scheme.

Instituting these supports for outdoor safety and quality is harder in anti-regulatory countries like the USA, or in lower-income nations, for instance South Africa, which don’t have the financial circumstances to invest as heavily in regulatory bodies, outdoor safety training standards, and the like.

Although the UK’s outdoor safety system is a global exemplar, it was clearly ineffective in this case, and MAIB points the way to improvements.

Singapore, after experiencing an outdoor adventure tragedy of its own, has begun work on a national standard for outdoor adventure safety and quality, which might offer an example that others could follow.

Effectively addressing all the factors that led to the SUP incident in Wales involves great complexity. But the UK has all the resources necessary to make good progress on improving safety in outdoor adventures.

To honor those who drowned on the Western Cleddau, and their loved ones, and for everyone who will take part in outdoor adventures, making those improvements in outdoor safety is essential.