Government Regulation Can Enhance Outdoor Safety Outcomes—If Well Designed and Implemented

Introduction

In August 2021, the Government of Maharashtra, a state in India, issued a Government Resolution on adventure tourism, prescribing regulations for safety of outdoor adventure activities. This is a big step for India and its second most populous state, Maharashtra.

We’ll take a look at the regulations, their development over several years, and how they might influence risk management in outdoor adventure programs.

We’ll also look at similar regulations across India and around the world, and how regulations may—or may not—influence outdoor safety. And finally, we’ll explore how regulations fit into the broader picture of good safety management in outdoor, adventure, wilderness and travel programs.

Adventure Tourism Activity Policy, Maharashtra

The adventure tourism regulation now in force in Maharashtra covers land-, air-, and water-based “organized adventure activities” “where there is a clear distinction between organizers and the participants and where responsibility of safety of participants is primarily transferred to organizers.”

Adventure sports competitions, school programs, and activities in nature sanctuaries regulated by the Forest Department are exempt.

Activity organizers are required to inform participants about the “adversities” that may be encountered and “care to be taken,” a risk communication that can help individuals give informed consent to participation.

Safety procedures such as providing directional maps, sirens at risky spots, and safety nets are required.

The regulation prohibits traffic hindrance, and betting is prohibited at the place of the activity. Restrictions on firearms and explosives are also described.

Adequate insurance coverage for the activities is required.

The Government Regulation, or GR, requires adventure tourism operators to take part in a two-step registration procedure.

First, organizers apply for a Temporary Registration Certificate from the Directorate of Tourism, good for one year. During this year, registration holders must acquire the trained staff, certified equipment, and other safety infrastructure necessary to meet detailed requirements outlined in safety guidelines (applicable to their respective adventure activities) from those attached to the regulation.

Organizers then have 18 months from the time the regulation came into force to obtain a final registration certificate. To obtain the final certificate, organizations must meet the requirements outlined in the safety guidelines, and may need to successfully pass a site inspection. The certificate is good for three years. An annual report must be provided to the government during this time.

Those who violate the regulations may be fined up to Rs.25,000/- (25,000 Indian rupees is approximately USD $335), have their equipment and office sealed, and be subject to criminal penalties. Violators may have their registration certificate canceled; the Director of Tourism may “blacklist” them, banning them from conducting adventure tourism activities in the state.

The Government Is Required to Provide Support

In addition to setting requirements for adventure tourism operators, the GR requires the government to provide certain support to the adventure tourism sector.

Maharashtra’s Tourism Department is required to create an Action Plan to provide equipment, training and financial assistance to support volunteer rescue groups to conduct rescue operations.

The Department will also establish a training centre for adventure tourism activities on land, air and water.

A state-level committee for adventure tourism is formed, including individuals from various state agencies and outside experts in land-, air- and water-based tourism activities. The group will develop incident investigation procedures, support promotion of adventure tourism, and otherwise advance adventure tourism in Maharashtra.

A divisional committee with government officials and external adventure tourism experts is formed. This group performs on-site inspections and conducts incident reviews.

Finally, an “Adventure Tourism Activity Cell” is created by the regulation. This also is composed of government officials and outside adventure tourism experts. The cell makes decisions on granting registration certificates, recommends outside adventure tourism experts to sit on the state-level and divisional committees, and grants star-ratings to registered Adventure Tourism Activity Organizers.

The full text of the GR, translated into English by the Maha Adventure Council, is available here. The official version in Marathi, the state language of Maharashtra, is here and also available on the Maharashtra government website.

A Brief Analysis of the Regulation

The regulation is less than a year old, and experience will demonstrate its strengths and opportunities for improvement. However, the regulation is promising, and appears to be a significant step forward in advancing safety and quality of outdoor programs in Maharashtra, which offers mountain ranges, coastline, rivers and forests ready for exploration.

Loopholes

Gaps in regulatory coverage can greatly influence a regulation’s effectiveness. School-based outdoor education programs, sports competitions like adventure races, and safaris in Forest Department wildlife sanctuaries are all exempt from the GR’s requirements.

However, there is precedent for excluding school and non-commercial entities from government regulations on adventure activities.

In New Zealand, schools are exempted from the Health and Safety at Work (Adventure Activities) Regulations 2016, which also exempts certain clubs and associations, among other carve-outs.

In the UK, schools are also exempted from the Adventure Activities Licensing requirements, which also excludes non-profit voluntary associations.

Likewise, the Swiss government’s 2019 regulations on safety in outdoor adventure activities (in French) apply only to activities “offered on a professional basis,” and exempts nonprofit clubs and associations.

These New Zealand, British and Swiss regulations also exclude certain outdoor adventure activities from coverage, whether due to a perception of lower inherent risk, lobbying by special interests during the drafting process, or for other reasons.

Adventure activities, if not covered by this GR, may however be regulated otherwise. Activities in Tiger Reserves and other Forest Department areas, for example, are subject to Forest Department guidelines. The safety guidelines attached to the GR note that in India, the Indian Mountaineering Foundation’s sport climbing competitions follow guidelines aligned with the rules of the International Federation of Sport Climbing.

What is Acceptable Risk?

One of the issues with which regulators–and adventure providers–must grapple is deciding what is an acceptable level of risk.

The GR, like any good regulation, is a dynamic document. We can expect that the issue of quantifying acceptable risk may be further developed in future revisions of the GR.

Similarly, the current English-language and unofficial translation of the original Marathi GR is undergoing a revision process that is expected to enhance clarity on this topic.

How have other regulators addressed the issue of acceptable risk?

The UK’s health and safety system, as outlined in the Health and Safety at Work etc Act 1974, that nation’s primary occupational health and safety legislation, requires risks to be reduced to a level as low as reasonable practicable, abbreviated ALARP.

New Zealand’s Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 uses essentially the same standard, using the synonymous term SFAIRP, so far as is reasonably practicable.

Australia’s Work Health & Safety Act 2011 likewise requires protection from risks so far as is reasonably practicable.

Site Inspection

Application of the on-site inspection discussed in the GR can increase the likelihood that adventure tourism operators will conform to safety standards. While it’s fairly easy to provide documents stating one conforms to risk management procedures, it’s harder to hide deficits from a skilled and impartial third-party observer on site.

Other safety legislation adopts an on-site inspection as a requirement. For instance, New Zealand’s Safety Audit Standard for Adventure Activities requires adventure operators to pass an external safety review, including observations of practice.

That said, auditors must be knowledgeable in how to conduct thorough audits, understand outdoor safety standards deeply, and be fully impartial. This is a relatively high bar, and it may take some time for a suitable pool of sufficiently qualified auditors to be developed in Maharashtra.

The inspection is specified as an “on-site” audit. For expeditionary programs that take place in the field rather than in a basecamp setting, an effective audit will need to evaluate participants during travel.

In addition, the on-site inspection component does not appear to have the level of development seen in the New Zealand and New Zealand analogues, which provide detailed guidance on topics including inspector competence, conduct of inspections, and assessment criteria.

However, it’s reasonable to expect that over time, this level of infrastructure to support a high quality of safety auditing in Maharashtra (Maha, for short) may emerge, just as the process has developed over many years in other jurisdictions.

Promising First Steps

The regulation promises to provide support for rescue operations, establish a training centre, and develop a star rating system. These have great potential to significantly increase safety outcomes if carefully and well developed, and sufficiently resourced on an ongoing basis.

Countries that are high-income and where outdoor recreation is a significant part of the economy—such as Iceland, New Zealand and Switzerland—tend to do well with establishing and enforcing high safety standards. In Maha, tourism is a significant economic driver (though not the main one in the highly industrialized state). However, India is not a high-income country with a low social risk tolerance. This means that considerable political will and sustained effort will need to be expended for these ideas to mature into highly functioning systems that are sustained over the long term.

Guidelines Accompanying the Regulation

The Government Resolution, 16 pages long, references detailed Safety Guidelines that provide specific operational standards for outdoor activities.

Those documents, comprising 267 pages of highly specific good practice standards, address safety guidelines for land-, water- and air-based activities: everything from trekking, “camping below 8,000 feet,” waterfall rappelling, ATVs, nature walks, kiteboarding, sea kayaking, parasailing, air safaris, paramotoring, and hot air ballooning, among others.

One appendix, “Annexure B,” is devoted exclusively to describing a Safety Management System for Adventure Activities. The document was based off the ISO 21101 international standard, “Adventure tourism—Safety management systems—requirements.”

The majority of the other appendices provide activity-specific information. For example: Appendix C, Safety Guidelines for Land-Based Activities, provides 118 pages of exquisitely detailed guidance on topics including pre-trip planning, suggested staff-to-participant ratios, behavioral norms such as drug use and intimate relationships between staff and participants, altitude gain limits in alpine travel, activity-specific equipment recommendations, recommended topics for safety briefings, first aid training for trip leaders, belaying technique for climbing traverses, bicycle chain lubrication, rappelling (abseiling) rope recommendations, required diameter of trekking ropes and ropes course cables, zipline braking systems, suggested first aid kit contents, and much more.

These guidelines have the appearance of a comprehensive policies and procedures manual for a well-established outdoor program. They include a mix of requirements, recommendations and suggestions.

The guidance is customized for the Indian context, discussing the importance of knowledge of Hindi, referencing specific locations (Gangotri, Leh) and activities (Sandhan Valley trek), cautioning not to disturb local ceremonies (jatra/urus), and respecting local customs such as vegetarian cooking when camping in temple sites.

An Enormous Accomplishment—But Continued Work is Required

Developing and making available well-developed guidelines for adventure providers in Maharashtra is a monumental achievement. Requiring conformity to the parts of the guidelines for which adherence is compulsory is another impressive accomplishment.

It will now take a significant investment on the part of regulated adventure providers to absorb this massive amount of material, create and enact internal procedures to conform to their contents, and establish how to document that conformity, as required by the GR. (The regulations provide an about 18 month period in which to do this.)

It will also take an investment on the part of the regulatory bodies to build the expertise to skillfully evaluate adventure providers, and to provide them the ongoing support necessary to help them successfully meet these standards.

When the New Zealand government instituted compulsory safety standards for adventure providers, they also provided funding for the sector to build a set of resources, known as SupportAdventure, to help outdoor programs understand and meet the new requirements. A similar arrangement for Maharashtra may prove important for the state government to foster.

Guidelines Created in Partnership with Industry

The detailed guidelines were developed with significant input from the Maha Adventure Council (MAC), an Indian nonprofit formed to help outdoor adventure programs achieve high standards of quality, safety, and environmental responsibility. The group, which includes outdoor adventure experts in a wide variety of fields, was formed in part to help ensure that regulations created by government officials could be informed by the views and unique knowledge of adventure specialists, and thereby made as useful and effective as possible.

The Indian Mountaineering Foundation, Association of Paragliding Pilots & Instructors, and Adventure Tour Operators Association of India were also involved.

If the regulation is to be successful, the fact that there was close industry participation (with a genuine interest in supporting the regulation’s safety promotion aim), and buy-in to the final product, may be a deciding factor.

Guidelines To Be Continually Updated

Annexure B of the regulation notes that “‘Safety Guidelines’ are dynamic in nature and will need periodic revisions on the basis of analysis of field data, developments in the field of adventure, and suggestions from the Adventure community.”

MAC leadership recognizes that the guidelines will require revision from time to time, and the Council can be expected to provide guidance to the Directorate of Tourism towards this end.

A History Maharashtra’s Adventure Tourism Regulation

The 2021 regulations didn’t come from nowhere.

As India developed over recent decades, interest in outdoor activities increased. Newly formed adventure companies filled the demand.

By the early 2000s, however, as both participation rates and the number of safety incidents increased, lawsuits in Maharashtra began being filed.

In 2007, following the death of a child who died on a Himalayan trek and the subsequent lawsuit, the Mumbai High Court directed the government of Maharashtra to develop a comprehensive safety policy and safety guidelines for organized adventure activities.

This led to the state government creating adventure tourism regulations in 2014. As explained in the preface to the current GR, however, these were challenged in the Mumbai High Court by outdoor specialists, who asserted the regulations were impossibly difficult to implement.

After a process of revisions, a revised GR was issued in 2018. This was again challenged in court by outdoor adventure providers.

The Tourism Directorate, Adventure Tour Operators Association of India (ATOAI), and newly-formed Maha Adventure Council then came together in 2020 to agree on improvements to the regulation, to take into account ATOAI guidelines, MAC expertise, and the relatively new ISO 21101 Adventure Tourism standards.

The result is the 2021 regulations and accompanying Safety Guidelines.

Maharashtra Government Sees Multiple Benefits to the Regulation

The state government sees value in improving safety for adventurers in Maharashtra, and the economic benefits that the regulation may bring.

As the GR was approved, Valsa Nair Singh, Principal Secretary of Maharashtra’s Tourism Department, said, “There are lots of fly-by-night people in the profession who are not following regular safety procedures. We have brought in registration and guidelines so that the safety and security of tourists is not compromised.”

State tourism and environment minister Aaditya Thackeray, who has an interest to “catapult the state onto the global tourist map,” added, “There were no rules related to adventure tourism and accidents were also happening…We want to encourage adventure tourism and send a message that it is safe for them. We want Maharashtra to lead in tourism once Covid pandemic is over.”

Outdoor Safety Standards in India and the Himalaya

The 2021 adventure tourism regulations represent one point in time in the development of outdoor safety practices in India and the Himalaya.

The Adventure Tour Operators Association of India, founded in 1994, has developed detailed safety guidelines for 31 activities (18 land-based, seven air-based, and six water-based). The second version of the standards was released in 2018.

These have been officially acknowledged by India’s Ministry of Tourism. In the 2021 GR, the state of Maharashtra directs that adventure operators based in that state who wish to conduct adventure tourism outside Maharashtra should follow ATOAI’s safety guidelines in those locations.

As India’s outdoor adventure industry developed over the last 40 years, other countries which share the Himalaya with India developed organizations, standards, and safety systems.

Outdoor safety standards in Nepal, for example, grew with the development of a variety of outdoor industry associations there, and the country passed climbing safety regulations in 2016.

In October 2021, the southern India state of Kerala passed adventure tourism safety regulations, similar to those in Maharashtra. The requirements, for 31 land, water, and air-based activities, were developed in consultation with outdoor adventure industry experts. Registration of adventure tourism operators is required, as is an on-site inspection is mandated. The registration is valid for two years.

On Regulation

Company executives, particularly in countries such as the USA where corporations hold outsize power, often resist the establishment of government regulations. These regulations, after all, may increase a company’s expenses, and limit the executives’ capacity to grow ever more wealthy.

And poorly executed regulations can cause unnecessary hardship for organizations—as the petitioners to the Mumbai High Court asserted in 2014, when protesting an earlier version of Maharashtra’s outdoor safety regulations.

Yet regulations, if skillfully written, appropriately enforced, and updated when needed, can have an enormously positive influence on the activities they regulate.

One can see regulation as a tool—a particularly powerful one—which, like any other tool, when used in the right way at the right time, can foster positive outcomes, and when not, can be ineffective or worse.

Regulations More Effective Than Voluntary Standards Alone

Scholarship on the subject of regulation has described three types of regulatory systems:

- Government regulation,

- Self-regulation, and

- Third-party regulation.

Researchers who study effective regulation note that self-regulation by itself—although favored by corporate interests—is often ineffective.

The pressure to cut safety corners in pursuit of maximum profit, and the lack of consequences for doing so, makes self-regulation “rarely effective in achieving social objectives because of the gap between private industry interests and the public interest,” according to an investigation commissioned by New Zealand’s health and safety authorities.

Limits to third-party regulation

Third-party review can be extremely effective, when standards are well-developed and reviewers are highly qualified. However, a recent review of New Zealand’s third-party adventure safety audit system revealed that complex and troubling weaknesses in the regime may exist, including the potential for regulator overreliance on certifiers to notify them of issues. The authors recommended review of the entire adventure activities regulatory design, including evaluating the concept of using third-party auditors.

Due to economic pressures, only two adventure activity auditors remain in the New Zealand market—down from the six that were envisaged to potentially be operating when the audit system was established in 2010. If one or both go out of business, the entire third-party audit system could collapse.

A 2018 report on New Zealand’s conformance system raised structural concerns about those systems, including the potential for the development of a compliance-based culture focused on box-checking, rather than seeing audits as adding value. This was noted as a risk for adventure activity providers particularly when a regulatory regime was new, or regulators were not nimble or able to suitably answer operator questions.

The issue of a “race to the bottom” with third-party auditors was also identified, where financial pressures may lead them to limit expenses and thus effectiveness of audits.

The report also found that the additional expense of the audit system was driving smaller adventure activity operators—who could most benefit from audit services—out of business, forcing a consolidation in the industry.

Seeking the Best of All Worlds

The optimal solution, research suggests, is a blend of all three types of regulatory regimes—compulsory government direction, self-regulation by companies, and oversight by third parties such as accrediting bodies.

This applies to outdoor and adventure activities, as well as any other industry or field.

Outdoor Safety Regulations Around the World

Government regulation of outdoor adventures is relatively uncommon. Only a small handful of countries—including New Zealand, the UK, Switzerland and Finland—have national-level outdoor safety legislation.

Sub-National Regulation

Some outdoor safety regulation exists at the state, province or canton level.

The Yukon Wilderness Tourism Licensing Act of 1999 in the territory of Yukon, Canada, is an example. The legislation requires wilderness tourism operators to have first aid-certified guides, hold adequate insurance coverage, and submit regular reports.

Various sub-national jurisdictions also regulate certain aspects of outdoor adventure activities, such as summer camps or ropes courses.

National Legislation: New Zealand

New Zealand’s Health and Safety at Work (Adventure Activities) Regulations 2016 is a global exemplar in high-quality outdoor adventure regulation. The regulations require operators to pass a safety audit every three years; the detailed safety audit standard requires the operator to maintain a Safety Management System which must describe incident prevention information, who is responsible for the SMS, and the organization’s commitment to continual improvement.

Safety goals and objectives must be set; roles and responsibilities must be made clear; communications processes must be maintained, and a risk assessment process must be implemented.

The operator must take measures to “eliminate serious risks arising from their activities, so far as is reasonably practicable.”

A drug and alcohol policy must be in place, operating procedures for each activity must be implemented, and staff must verifiably be competent for their assigned tasks.

Additional standards cover participant supervision, clothing and equipment, field communications, emergency response plans, incident reviews, and document control, among others.

National Legislation: United Kingdom

Following a multiple drowning incident of school children in Lyme Bay on the south coast of England in 1993, the UK enacted Adventure Activities Licensing Regulations to help ensure good safety practices for outdoor programmes for youth in the UK.

The regulations cover caving, climbing, trekking, and watersports. They apply only to commercial activities provided to young people under the age of 18.

Criteria for licensure include a safety management system that creates a positive safety of culture, includes systematic planning methods, has appropriate risk control monitoring, maintains effective communication, and provides for periodic performance review.

Competent persons must manage safety; sufficient and suitably qualified staff must be present; safety information must be conveyed; suitable equipment must be maintained; and emergency procedures should be documented.

Just as New Zealand provides support for adventure operators to understand and conform to outdoor safety regulations, the UK provides guidance to help UK-based operators understand and meet their safety obligations under the regulations.

National Legislation: Switzerland

In the afternoon on July 26, 1999, a group of young people, led by guides from a well-known local adventure company, were canyoning through Saxet Gorge in Switzerland’s Bernese Oberland. A flash flood swept through the canyon. Twenty-one people died. Most of their bodies were recovered, although the body of a 25-year-old Australian woman who was on her honeymoon with her husband was never found.

The company closed its doors (after experiencing a fatal accident the following year, where a young American died on a bungee jump because the rope was too long and did not break his fall). Six employees of the provider (including three board members) were convicted of negligent homicide. They received three- to five-month suspended sentences and fines of 4,000 to 7,500 francs (USD $4,300 to $8,200).

Following the incident, the outdoor adventure industry reportedly resisted the introduction of outdoor safety legislation, asserting that voluntary guidelines were adequate.

Nevertheless, the Swiss government created outdoor safety legislation. Outdoor safety legislation at the canton (sub-national) level has also been established.

The federal legislation has been evolving relatively rapidly in recent years, and was overhauled in 2019, with new rules for “high-risk” sports and guided mountain activities. The 2019 version replaced the 2014 regulations on mountain guides and organizers of other “high-risk” activities, which included canyoning, alpine hikes, rafting and bungee jumping. The new regulations also address skiing, snowshoeing, via ferrata, ice climbing, glacier travel, and whitewater river travel (by methods including “canoe, kayak, hydrospeed, funyak or tubes”).

Liability insurance requirements, penalties for non-conformity, and detailed requirements for leader training and certification by organizations such as the Swiss Mountain Guide Association are included.

The 2019 regulations are based on the ISO 21101:2014 adventure tourism safety standards, which did not exist when the original legislation was drafted. They also incorporate other ISO standards, such as ISO 17021, on management system auditor standards, and ISO 21102, on adventure tourism leader competence.

Regulatory objectives are expressed with Swiss precision: an aim is the achievement of fewer than five deaths per 10 million hours of activity. This is acknowledged to be a risk three times lower than riding a motorcycle in Switzerland—but greater than the risk of experiencing a fatal injury by cycling, which the regulation notes as 1.3 deaths per 10 million hours of activity.

These measures are notable for their attempt to add objectivity to the inherently subjective risk management aims of other national health and safety bodies, which seek to reduce risks as much as is “reasonably practicable.”

National Legislation: Finland

Finland, like other Nordic countries, has a relatively high proportion of natural and wilderness areas, and a tradition of outdoor recreation.

In the 1990s, the Finnish Ministry of Education and Consumer Safety Bureau asked leaders of Outward Bound Finland to develop a safety review system for youth organizations, and provided two years of funding for the project.

The result was SETLA—Seikkailu-Ja Elämystoimialan Turvallisuuden Laatu-ohjelma—or Adventure and Outdoor Programs Quality of Safety Program.

In 2011, Finland passed a Consumer Safety Act and a Safety Document Decree, legislating safety requirements for outdoor and other programs. The law includes requirements for risk assessments, first aid, rescue, search, and evacuation.

Outdoor safety requirements in the legislation were built on the SETLA framework. Its work having been folded into national legislation, the SETLA project then closed around 2013.

But because the outdoor safety standards had been originally developed by Finnish outdoor adventure experts, the legislation is more likely to be well-received by and useful to outdoor organizations in Finland, compared to legislation drafted without such consultation.

National Standards: Australia

Australia has no national legislation specific to outdoor safety. It does, however, have a well-developed set of voluntary standards, the Australian Adventure Activities Standards.

The standards were originally developed in one Australian state, at least in part to establish common safety practices that could lead to a reduction in insurance premiums outdoor programs had to pay. However, a patchwork of state-level standards soon were seen as unworkable, as many outdoor adventure providers in Australia provided activities in multiple states.

A four-year process ending in 2019, funded by state Sport and Recreation authorities, led to a unitary set of voluntary minimum standards for the led outdoor activity sector with dependent participants.

While these standards are not regulations, they are so well-developed as to be worth mentioning with respect to examples of good national-level outdoor safety guidance.

Although Australia may be less amenable to regulation than its culturally distinct neighbor New Zealand, a next step for the Australian led outdoor activity sector might be to ponder establishing a regulatory framework that makes standards conformity compulsory, and helps reduce the potential of certain operators to cut safety corners with little consequence.

Adoption of ISO 21101 Adventure Tourism Safety Management Systems

Maharashtra’s new adventure tourism safety regulations are based off of ISO 21101, which outlines the requirements of a safety management system for adventure tourism activity providers.

Kerala’s brand-new outdoor safety regulations are as well, as are the most recent Swiss regulations.

The New Zealand government has raised the issue of adopting ISO 21101 as the framework for developing a new adventure activities safety audit standard.

The standard was first developed in 2014, and reviewed and confirmed in 2019 as part of the every-five-year ISO standard review process. It’s part of a three-document suite of adventure safety standards, which also includes ISO/TR 21102 (Adventure tourism — Leaders — Personnel competence) and ISO 21103 (Adventure tourism — Information for participants).

The document set appears to provide a credible and useful framework upon which regulators around the world can build region-specific safety requirements.

However, caution is in order. There are two principal concerns to consider: the high-level nature of the standard, and the incident causation model upon which it appears to have been developed.

ISO Provides Generic, High-Level Guidance Only

ISO 21101 provides only high-level guidance. In essence, it outlines a process by which entities can create a safety management system for any purpose, in this case adventure tourism activities. It does not, however, specify what the contents of that system should be.

Therefore, without a great deal of additional detail, the application of the standard will not result in the comprehensive, actionable information necessary to successfully manage risk.

The ISO, in essence, outlines a risk management process applicable to practically any activity, including adventure tourism:

- Establish the context. The organization should define its activities, objectives, and risk assessment criteria.

- Perform a risk assessment. The organization should identify risks, determine their likelihood and severity, and establish which require treatment (to be reduced to an acceptable level), for example by using probabilistic risk assessment (PRA) spreadsheets.

- Perform risk treatment. The organization should “establish, implement and maintain a risk treatment process.”

The standard stipulates that the organization’s top leadership should take actions such as ensuring adequate resources, establishing relevant policy, clarifying roles and responsibilities, and promoting continual improvement necessary to help ensure the system achieves its intended outcomes.

The standard requires conformity with legal requirements and that the organization “establish adventure tourism safety objectives at relevant functions and levels.”

Involved persons, according to the standard, must have appropriate competence and suitable awareness of the safety policy, their contribution, and implications of non-conformance.

Communications, documentation, and operational planning and control must be suitable. Emergency management plans must be developed, and a performance evaluation and management system instituted.

The process described could be applied to virtually any organization in any field of endeavor—from adventure tourism to modern dance instruction to manufacture of plastic Christmas trees.

Users of the standard must understand that it is extremely generic, and provides no guidance as to what appropriate outdoor safety standards might be—it just outlines a process by which those standards may be developed and applied.

However, as long as this caveat is understood, and the additional detail is provided—as the Maha annexures provide in spades, and the detailed Swiss legislation offers in crisp detail—then this concern can be considered addressed.

ISO’s Approach to Risk Management Is Not Systems-Informed

ISO 21101’s approach to the management of risks is based off of another ISO standard, ISO 31000, Risk management — Principles and guidelines.

This standard fleshes out the three-part process described above (establish the context, perform a risk assessment, perform risk treatment), in somewhat greater detail. However, the fundamental underlying structure—identify each risk, and make a treatment plan for it—remains the same.

This approach to risk management has been criticized in the literature as being outdated and of limited effectiveness, compared to more modern and sophisticated approaches to understanding incident causation and managing risk.

The principal concern is that this approach reflects a linear-based model of understanding how incidents occur, and therefore how they might be prevented. This linear model, established in the 1930s, has been superseded by a more advanced understanding of incident causation, namely, a model that employs complex socio-technical systems theory to look at risk in complex systems such as led outdoor activities.

This systems-informed model takes into account that incidents sometimes occur from a number of risks that combine in impossible-to-predict ways. Building resilience into an organization’s risk management infrastructure, then, to withstand unexpected failures of components of the risk management system, at unknown times and in unanticipated ways, is essential to building an effective safety management system.

(This systems-informed approach has been described using a variety of terms, including Safety Differently, Safety-II, Guided Adaptability, and High Reliability Organizations.)

As long as ISO 21101 depends on an underlying model seen by some leading safety thinkers as out-of-date and suboptimally effective, it exposes organizations that use it to unnecessary risk.

Factors Influencing the Effectiveness of Regulations

Continuous Improvement

Whakaari/White Island is an oval-shaped island lying some 50 kilometers from New Zealand’s North Island. It’s an important gannet nesting area, and a listed scenic reserve. It’s been a popular tourist destination for years.

It’s also an active volcano.

On December 9, 2019, 47 people, mostly tourists from a passing cruise ship, were on the island, observing its unique geology. Some were right next to the volcano’s active vent.

At 2:11 pm the island erupted. In a series of violent blasts, the volcano exploded, spewing a column of ash 12,000 feet in the air, showering the island with hot, rocky debris.

Twenty-two people died. The remaining 25 were seriously injured, with major burns to their skin and lungs. The bodies of two were never found.

New Zealand has what some consider to be the world’s leading outdoor adventure safety regulatory scheme, put into place to prevent incidents like the devastating Whakaari/White Island tragedy.

Due to its history of volcanic eruptions, the island is heavily monitored by scientists. Seismic rumblings and gas emissions had been rising, so authorities raised the volcano’s alert level to 2, indicating “moderate to heightened volcanic unrest.”

So how could this terrible mass casualty even have happened? In a region with a world-class adventure tourism safety system, at a location with hazards continually scrutinized by experts, how did things go so catastrophically wrong?

The incident is a sad and humbling reminder that even the best safety systems are imperfect. Even the most highly developed risk management schemes may not prevent all incidents.

The incident shows the need for adventure tourism safety systems to invest in a process of continuous improvement. Critics identified faults in the current risk management system. And, following the eruption, the government completed a targeted review of the adventure activities safety regime, which concluded that the system was generally performing well but had some aspects that could be strengthened.

In September 2021, the New Zealand government proposed improvements to the country’s adventure safety regulations.

The proposal will improve risk assessment of natural hazards, and require operators to have clear protocols for canceling activities due to unacceptably high levels of risk. It would improve the disclosure of risks to participants, and make changes to how WorkSafe, the country’s safety agency, operates.

Some improvement efforts will commence immediately, while others are scheduled to start in 2023.

Effective Enforcement

Drafting regulations is one thing. Effectively enforcing them is another.

High-income countries with well-developed adventure activities regulation regimes, such as New Zealand, have identified challenging problems in the structure of their regulatory systems. Other countries, however, don’t suffer so much from imperfections in their assurance and inspection regimes, as a frank absence of effective enforcement of regulatory requirements.

This is particularly an issue in jurisdictions where economic pressures and associated socio-cultural influences lead to a near-absence of enforcement of regulation.

Regulation’s Place in a Comprehensive Risk Management System

Regulation clearly has a valuable place in supporting a high quality of safety management in outdoor and adventure programs. But how does it fit in the larger picture of influences on good outdoor safety?

A variety of theoretical models have been proposed to explain why incidents occur, and by extension, how they might be prevented. Rasmussen’s AcciMap and its many variants are leading examples.

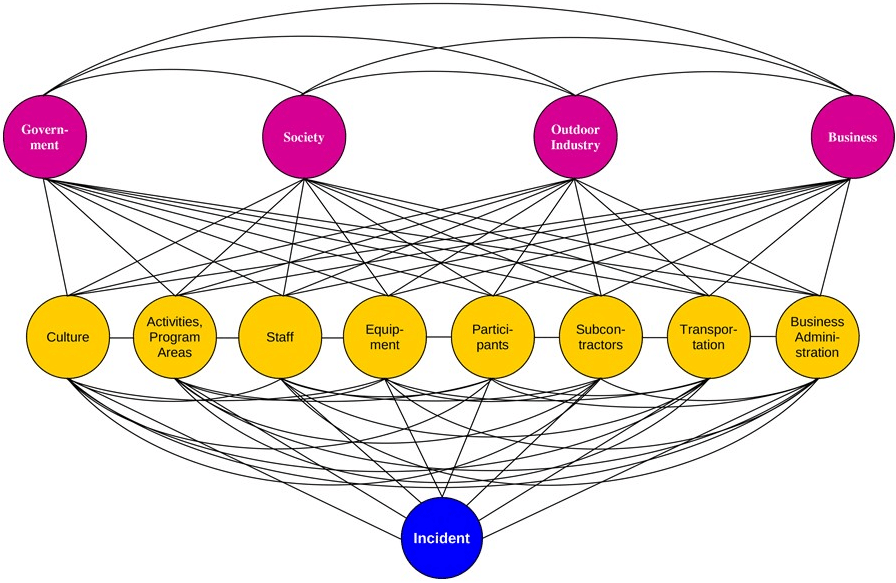

Another model for illustrating the factors involved in risk management—for outdoor, adventure, wilderness, travel and experiential programs, in particular—is the Risk Domains model, below.

Risk Domains

In this model, risks that can directly lead to an incident are contained in eight “direct risk domains,” in yellow, above. These are:

- Safety culture

- Activities and program areas

- Staff

- Equipment

- Participants

- Subcontractors (providers)

- Transportation

- Business administration

Risks in these areas that may be present in an outdoor program should be identified. Policies, procedures, values and systems should be instituted to reduce those identified risks to a socially acceptable level.

Risks are also present in four “underlying risk domains,” in fuchsia, above. These are:

- Government

- Society

- Outdoor Industry

- Business

Factors here can indirectly influence incident causation.

Underlying Domain: Government

For example, in the Government domain, well-developed regulation, effectively enforced, can powerfully support excellence in safety management. We vividly see the potential for this in the Maharashtra regulations and safety guidelines.

In a more nuanced example of how the Government domain can influence safety outcomes, we can look at the role of insurance and liability in outdoor risk management.

The Maharashtra regulation currently states, “If Adventure Tourism Activity is conducted without following the rules and conditions laid down by government and if any hazard is caused to people, then the concerned persons will be charged with culpable homicide.” This is a relatively strict standard, and the language here may be modified in future GR amendments.

The standard in the Maha GR can be contrasted to the system employed in New Zealand by that country’s Accident Compensation Corporation under the Accident Compensation Act 2001. New Zealand’s ACC scheme is a unique no-fault accident insurance system where those harmed in an adventure tourism (or any other) activity in the country are provided care and compensation for their loss.

As part of the scheme, injured parties are generally prohibited from suing the at-fault organization for damages. However, the organization can be liable for workplace health and safety violations.

The ACC Scheme’s less-punitive method of addressing incidents in adventure tourism operations has been credited with fostering a robust and innovative adventure tourism sector in New Zealand, and contributing to the country’s economic wellbeing.

(In the Whakaari/White Island case, the New Zealand government’s health and safety agency, WorkSafe—itself under investigation for alleged shortcomings related to the disaster—in a rare step, charged several adventure tourism operators, the island’s land managers, and even two government agencies—the country’s earth-science research agency GNS Science, and the National Emergency Management Agency—with potential criminal health and safety violations.)

Underlying Domain: Society

In the Society domain, a low social tolerance for risk can support good safety outcomes. The public interest lawsuit following the death of a child in the Himalaya in 2006 illuminated a reduced social tolerance for such tragedies, and directly led to the Maharashtra regulation. Similarly, an extended public outcry in the 1990s—and sustained pressure from parents of the victims to members of the British Parliament—led to the formation of the seminal Activity Centres (Young Persons’ Safety) Act 1995 in the UK, and the subsequent Adventure Activities Licensing Regulations 1996, following the deaths of four students on a 1993 kayaking trip in Lyme Bay.

Underlying Domain: Outdoor Industry

The Outdoor Industry has an important role to play as well. In the Maharashtra case, the Adventure Tour Operators Association of India, Indian Mountaineering Foundation, and Maha Adventure Council were among outdoor industry groups that provided support in the creation of the regulation and supporting safety guidelines, helping ensure that they were of the highest quality and utility possible.

Underlying Domain: Business

And finally businesses, principally large corporations, can support good safety outcomes—including on adventure tourism outings—when they exhibit a sense of civic responsibility by supporting sensible regulation, paying their fair share of taxes, and supporting efforts of government to act in the best interests of the people it represents, not just the most privileged and powerful.

Risk Management Instruments

In addition, the Risk Domains model identifies 11 “risk management instruments” which can be used to reduce risks across many or all risk domains:

These include:

- Risk Transfer: insurance, subcontractor, participant waivers

- Incident Management: emergency response plans and drills

- Incident Reporting: documentation and analysis of mishaps

- Incident Reviews: formal evaluation of major incidents

- Risk Management Committee: a group including external voices to provide guidance

- Medical Screening: to ensure a good medical match between staff/participants and activities

- Risk Management Reviews: proactive safety audits

- Media relations: training for effective media management during crises

- Documentation: durably recording what should be and has been done

- Accreditation: third-party review of standards conformity

- Seeing Systems: use of complex systems theory in safety management systems

Together with policies, procedures, values and systems that help reduce specifically identified risks in all risk domains to a socially acceptable level, these instruments can comprise a high-quality risk management system.

More information on this model can be found in the textbook Risk Management for Outdoor Programs: A Guide to Safety in Outdoor Education, Recreation and Adventure.

Additionally, a forty-hour online training, held over one month, provides an opportunity to explore this model in greater detail.

Limitations of Incident Prevention Models

Some caveats about the Risk Domains model—and any model of incident prevention—apply.

No model, by definition, is a perfect representation of the reality it attempts to portray. Models are simplifications which are used to illuminate certain key characteristics of a thing, not a wholly identical replica.

Incident causation/prevention models, then, may be best seen as tools—a resource that can help reduce the probability and severity of an incident, when used in an appropriate way at an appropriate time, and an item that can be useless or even harmful if employed in inexpert or unthoughtful ways.

The Risk Domains model was recently applied in an incident review at a large university where a student was injured on a backpacking outing. One of the issues identified in the review was that the university’s organization chart—its hierarchical structure of personnel, supervision, and responsibilities allocation—did not do a good job of supporting system-wide communication about outdoor-related risks, and the system of performance-based incentives and rewards embedded in the org chart inhibited good system-wide management of risks. However, the Risk Domains model does not do a great job of explicitly including organizational chart analysis in its structure (although many alternate models do no better); this points out how no model is perfect, but that all models, to be maximally useful, must be employed with thoughtfulness and skill.

How do we stop airplanes from falling out of the sky, killing everyone aboard? How do we bring motor vehicle accidents to zero? In what way, short of ceasing the activity altogether, can we ensure no persons ever twist their ankle on a hike?

The only honest answer to these questions is, “We don’t know.” We don’t know how to 100 percent put a stop to human error. We don’t have a theoretical model whose application will bring incident rates to zero, forever.

However, there are ever-improving models—the best and most current, incorporating elements of complex socio-technical systems theory—that, when used with skill and care, can reduce the risks of outdoor adventure to a socially acceptable level.

Conclusion

The approval of adventure tourism safety regulation in Maharashtra, India is a great step forward for the outdoor profession in that state, and the participants who experience the joys of Maharashtra’s beautiful mountains, forests, rivers and coastline.

This remarkable achievement is the result of outdoor education and outdoor recreation experts in India, and many others, who came together to craft a system that can elevate the safety and quality of travel and adventure experiences for all.

The Government Resolution and its accompanying Safety Guidelines are an essential part of a larger risk management world that can support positive safety outcomes for adventurers in Maharashtra—whether they are climbing or paragliding in the Western Ghats, experiencing a jungle safari in the Tadoba Andhari Tiger Reserve, or whitewater rafting on the Kundalika River.

But regulations are hard to do well. It’s tricky to find the right balance between providing helpful rules on the one hand, while avoiding the creation of burdensome and out-of-date restrictions on the other.

However, when regulations are well written, enforced appropriately, and paired with other elements that support good risk management, they are a great benefit to all.

The author wishes to thank Shantanu Pandit and his colleagues on the Maha Adventure Council for vital support provided in the development of this article.