A Review of Linear-Based and Systems-Informed Safety Thinking

Introduction

Professionals with responsibility for managing risk may have heard the terms “Safety-I” and “Safety-II” in recent years. Those who might have encountered these phrases include individuals responsible for safety in outdoor, experiential, wilderness, travel and adventure programs. But what do those terms mean? How do they apply to the day-to-day activities of outdoor safety managers?

We’ll address these questions below, and help make clear what “Safety-I” and “Safety-II” mean for those who manage risk in outdoor and related programs.

Summary

What we’ll discuss in the following pages can be summarized as follows:

- Safety-I describes a linear model of safety management, suitable only for simple situations

- Safety-II describes a safety management model informed by complex socio-technical systems theory, and is well-suited to managing complex situations

- These models work for managing risks in outdoor programs and elsewhere

- Many other terms, such as guided adaptability and Safety Differently, also describe a systems-informed safety management model

- Both linear (Safety-I) and systems-informed (Safety-II) risk management approaches should be used

- A specific systems-informed risk management model using Risk Domains and Risk Management Instruments can be employed in outdoor programs.

- Techniques for applying systems thinking to outdoor safety include resilience engineering (such as having extra capacity, and balancing rules and judgment), considering all risk domains, and using systems-informed planning tools such as a ‘pre-mortem’

What do Safety-I and Safety-II mean?

The terms Safety-I and Safety-II refer to linear-based and systems-based safety thinking.

“Safety-I” describes an older approach to understanding risk management, based on a linear progression of causes leading to an incident.

“Safety-II” describes a more highly developed, or second-generation approach to understanding why incidents occur (and how they can be prevented)—a model that is seen as more accurately describing complex incident causation, and which is based off complex socio-technical systems theory.

(We consider “safety management” and “risk management” interchangeable, for the purposes of this discussion.)

Safety-I, or linear-based safety thinking, provides useful tools for managing risk. Safety-II, or systems-informed safety thinking, adds additional tools to how we may approach managing risks.

Ideas from both Safety-I and Safety-II should be used in a comprehensive risk management structure; one is not inherently better than the other. For optimal risk management, Safety-I and Safety-II principles should be used together.

Alternatives to the “Safety-I/Safety-II” term

The concepts described in the Safety-I/Safety-II literature have also been described using the terms ”high reliability organisations,” “resilience engineering,” and “Safety Differently.”

Although the terms “Safety-I” and “Safety-II” have entered the risk management lexicon, we can also consider using descriptors that may have, when used without immediate context, greater meaning:

Safety-I: Linear-based safety thinking

Safety-II: Systems-informed safety thinking

We’ll use both sets of terms interchangeably, below.

History of the Safety-I and Safety-II Concept

The terms “Safety-I” and “Safety-II” were coined in 2011, and most fully described in a 2014 academic textbook titled Safety-I and Safety-II, written by the eminent Danish academic Erik Hollnagel, Senior Professor at Jönköping Academy, Sweden.

The textbook provides a detailed and academically rigorous look at Safety-I and Safety-II concepts, and is well-suited for those interested in a wide-ranging intellectual dive into safety and other topics.

The concepts described by the terms Safety-I and Safety-II, however, are not entirely novel. They can be seen as a re-framing of systems thinking, specifically the application of ideas from complex socio-technical systems (STS) theory to the field of risk management.

Any concept can be explained in different ways and from a variety of perspectives. This is often useful for illuminating particular aspects of a complex concept, or exploring how the concept can be applied in certain contexts. When a set of ideas is synthesized and reframed—such as describing complex STS theory applied to safety as Safety-I/Safety-II, or describing Safety-I/Safety-II as linear-based/systems-informed safety thinking—opportunities arise for new understandings and new uses for concepts by new audiences.

Some models become more widely adopted than others. The Safety-I/Safety-II model has been applied to healthcare, aviation, and outdoor fields. How these concepts will be understood, named, and advanced in the future remains to be seen.

While the terms Safety-I and Safety-II are relatively new, the underlying idea of systems thinking is not. Systems thinking applied to the professional endeavor of risk management is relatively new, in the history of safety thinking. However, systems thinking itself is likely an ancient concept. Indigenous ideas about interconnection stretch back thousands of years, before the growth of the rational reductionist scientific mindset that one can see today.

Applications of Linear And Systems-Informed Safety Thinking

Do the concepts of Safety-I and Safety-II, or linear-based and systems-informed safety thinking, apply to me?

If you’re a professional involved in an outdoor-related field, yes. These ideas can be useful across many outdoor-related disciplines—outdoor education, outdoor recreation, experiential education and experiential learning, and outdoor adventurous activities of all types. Organizations involved in Search and Rescue have applied systems thinking to managing risks. So have those in the environmental conservation/restoration field, such as with conservation corps programs.

Professionals involved in wilderness risk management, outdoor and travel risk assessment, and safety management of experiential programs worldwide can usefully apply these ideas to their program’s management of risk.

Safety-I and Safety-II, along with other systems-informed models of risk management, arose largely in response to the mechanized risk management systems in place in large industrial and bureaucratic settings such as factories, power plants, and hospitals. Many well-run, larger outdoor education programs, however, have been integrating aspects of systems-informed risk management in their practice for many years. The approaches described here will appear familiar to individuals in those organizations.

Safety-I and Safety-II Risk Management in Detail

Let’s look more closely at what Safety-I and Safety-II entail.

We recall that Safety-II, or systems-informed safety thinking, builds on the ideas Safety-I or linear-based safety thinking. We’ll look more closely at both of these approaches to managing risk.

There are many ways to explain linear-based and safety-informed thinking. Here we’ll present information that is of practical value and useful to know.

Across 180 pages, the Safety-I and Safety II text referenced above talks about many other subjects, such as a proposition to avoid the idea of ‘causality;’ these explorations may be more intellectually interesting than of direct practical use, and are not covered here.

Safety-I, or Linear-Based Safety Thinking

In linear safety thinking, an incident occurs, which has one or more, typically identifiable, causes, which lead to the incident. This progress of cause or causes à incident occurs in a logical, straight-line sequence.

This, however, is generally not how incidents, particularly major incidents, occur. But since the start of the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century, this has commonly been how incidents have been viewed.

This linear chain-of-causation thinking is exemplified in the following 13th century nursery rhyme:

For want of a nail the horseshoe was lost.

For want of a horseshoe the horse was lost.

For want of a horse the rider was lost.

For want of a rider the battle was lost.

For want of a battle the kingdom was lost.

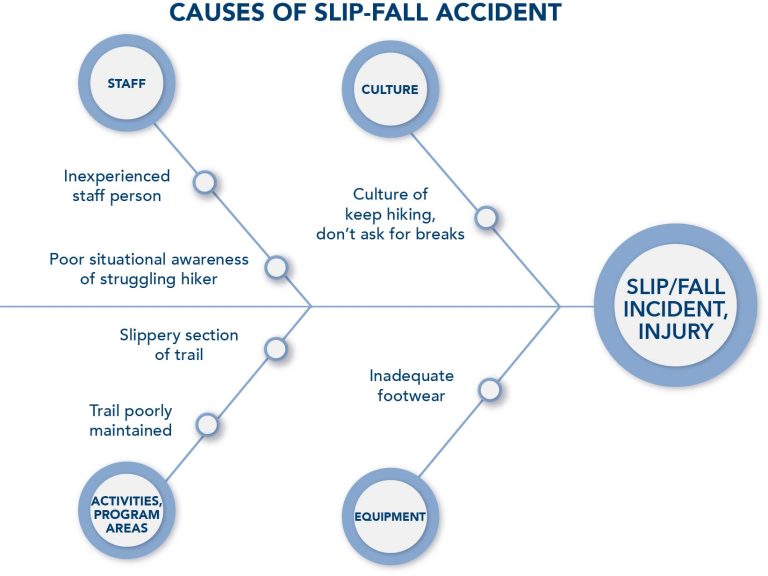

The fishbone diagram is used to illustrate the cause-and-effect relationship. An example, showing the causes of a hiker’s slip and fall, resulting in an injury, is below.

Safety-II, or Systems-Informed Safety Thinking

A systems-informed approach to safety provides a more accurate model of how incidents, particularly major ones, occur. This model, based off of complex socio-technical systems theory, is better able to address complex incidents (or complex problems).

Examples of complex problems include preventing a critical incident, such as a permanently disabling injury. They also include the global climate emergency, and international refugee flows.

All of these are examples of things that take place in a complex socio-technical milieu, of people and technology. Problems are best addressed by applying solutions of a level of complexity equal to that existing in the problem to be resolved. These issues, then, are best addressed using systems thinking.

Characteristics of complex problems requiring systems thinking include:

- Difficulty in achieving widely shared recognition that a problem even exists, and agreeing on a shared definition of the problem

- Difficulty identifying all the specific factors that influence the problem

- Limited or no influence or control over some causal elements of the problem

- Uncertainty about the impacts of specific interventions

- Incomplete information about the causes of the problem and the effectiveness of potential solutions

- A constantly shifting landscape where the nature of the problem itself and potential solutions are always changing

Incidents Occurring Within a Complex System

Let’s look briefly at three examples of complex incidents best resolved by applying systems thinking. The first, involving disease prevention, illustrates the complexity of systems in general; the latter two are specific to outdoor programs.

Parachuting Cats

In the early 1950s, the Dayak people in Borneo suffered from malaria.

The World Health Organization had a solution: they sprayed large amounts of the pesticide DDT to kill the mosquitoes that carried the malaria. The mosquitoes died; the malaria declined. So far, so good. But there were side effects.

Among the first was that the roofs of people’s houses began to fall down. It seemed that the DDT was killing a parasitic wasp that had previously controlled thatch-eating caterpillars.

Worse, the DDT-poisoned insects were eaten by geckoes. The geckoes, in turn, were eaten by cats. The cats died. The rat population, previously controlled by cats, boomed. People now were threatened by outbreaks of rat-borne sylvatic plague and typhus.

To cope with these problems, which it had itself created, the World Health Organization called in the Royal Air Force-Singapore to parachute up to 14,000 live cats into Borneo.

The presence of a complex system, where an initial intervention has unintended consequences, is evident.

Ropes Course Fatality

A 17-year-old boy suffered a fatal fall off a home-made giant swing at a ropes course in Victoria Australia in 2001.

The child fell about 10 meters to the ground on his head as he was preparing to ride upside down on a giant swing-type activity called “The Rip Swing.”

The participant was attached by a single screw-gate carabiner, which was attached to a second screw-gate carabiner, which was attached to a cable. A tow rope, used by helpers on the ground to manually haul the participant to height, was attached to the second carabiner at a 90 degree angle. Although it was recognized that a participant positioned upside-down increased risks of carabiner unscrewing and head injury, this was permitted.

The investigation cited a variety of causes, including:

- Improper use of carabiners

- Lack of required backup or fail-safe systems, as specified in the relevant Australian Standard

- Participant was improperly positioned upside-down, in a way in which the Rip Swing was not designed to be used

- Victorian WorkCover Authority (the government’s health and safety agency), which had inspected the facility repeatedly over multiple years, failed to identify unsafe swing operation

- The Camping Association of Victoria (which assessed the site as part of its voluntary accreditation program) failed to comment on the lack of fail-safe backup, and, as accreditation is voluntary, was unable to prevent future incidents due to lack of authority

- Occupational safety legislation was deficient. The Rip Swing did not fall under Health and Safety regulations owing to a loophole which exempted any item that “relies exclusively on manual power for its operation.”

- Government certification and inspection of adventure facilities was absent

The investigator found causes far beyond the actual ropes course device, implicating the facility operator, the health and safety agency, the industry association, and the state Legislature.

Multiple Drowning at Outdoor Education Centre

In 2008 at a well-respected outdoor center in New Zealand, seven participants on an outdoor adventure program drowned in a flood during a canyon hike through Mangatepopo Gorge. The outdoor centre had been running for over 30 years, and had numerous safety systems in place.

Yet investigations showed a variety of contributing factors, involving safety culture, equipment, staff training, administrative practices, weather agency operations, and government oversight, among others.

The factors included:

- The organization had a history of blaming staff for accidents, rather than addressing underlying issues

- Participant swimming ability, required by Centre policy to be assessed, was not checked, nor was there any routine system to do so

- Program management did not read the weather map supplied to the Centre by MetService (the national weather service), which would have alerted staff about heavy rain

- The instructor was not formally assigned a mentor, who could provide safety guidance, as described in the Centre’s policies

- Staff to participant ratios were inadequate

- The instructor was permitted to lead the Gorge trip without having read and signed the Risk Analysis and Management System document describing Gorge risks and management strategies, as required

- A map of the gorge with emergency escapes was available, but was never given to the instructor. Contrary to Centre policy, the instructor was never shown and familiarized with all the emergency escapes

- The group passed by a “high water escape” shortly before sheltering from floodwaters on a ledge, but due to inadequate instructor training and experience, did not take advantage of it

- A radio communications system to eliminate spots of no radio reception in the canyon was not in place

- Radio procedures were unclear to rescuers, leading to confusion and inefficient communications

- The Instructor Handbook was not sufficiently correlated with the Risk Analysis, and the Risk Analysis document was incomplete

- A documented history of problems with instructors with inadequate experience or program area knowledge, inadequate supervision ratios, and flood incidents was not addressed

- The impact of financial pressure led to pressure to accept bookings even if suitable staff were not available

- The weather report issued by MetService used by staff mistakenly omitted the word “thunderstorm,” which could have alerted staff to heavy rains

- MetService did not follow up to address the error in its forecast

- The New Zealand government did not ensure safety standards for outdoor adventure programs were met, for example by a licensing scheme

- An external safety audit by the outdoor industry association was being conducted on the day of the tragedy. Despite the death and the many issues leading to it, those issues were not addressed in the audit.

Other terms used to describe the concepts of “Safety-I” and “Safety-II”

We’ve described Safety-I as linear-based safety thinking, and Safety-II as another name for systems-informed safety thinking. Theoreticians use other terms to explain these two contrasting approaches to management of risk.

Some terms (such as “resilience engineering”) may be more easily understood or be somewhat self-explanatory; others (such as “Safety-II”) may inherently mean little without additional context.

Alternate descriptors may approach the Safety-I – Safety-II dichotomy from a slightly different perspective, or emphasize varying aspects of the difference in the approaches to risk management. Risk managers can adopt whichever terms seem most useful for them and their context.

Centralized Control and Guided Adaptability

One alternate set of terms that attempts to describe the characteristics of Safety-I and Safety-II, used by Griffith University’s David Provan and others, is centralized control and guided adaptability.

“Centralized control” refers to the process of organizing and controlling the organization and its staff through a central determination by executive management of what risks and control measures are appropriate. “Guided adaptability” refers to supporting individuals and the entire organization to continually anticipate emergent risks and—without reliance on rules established by executives—to adapt to, or effectively respond to, those novel issues and challenges.

Plan and Conform, and Plan and Revise

Other terms used to express the same two approaches include “plan and conform” and “plan and revise.” In “plan and conform,” executives develop safety management plans, and personnel follow the plans. In “plan and revise,” pre-established plans are still drawn up, but it is expected that deviation from the plan will be necessary, in order to appropriately respond to unforeseen circumstances.

Safety Differently

Sidney Dekker, also of Griffith University, uses the term “Safety Differently” to describe what Hollnagel characterizes as “Safety-II”—fundamentally, building the capacity of workers to adapt and make good decisions to effectively respond to the ever-changing risk environment, rather than focusing safety efforts on imposing rigid top-down rules on workers.

Resilience Engineering

The actions taken from a Safety-II perspective are also described as “resilience engineering.” Resilience engineering focuses on building the capacity of a system to successfully adapt so as to continue normal operations despite unanticipated challenges and deviations, based off of the understanding that in complex systems, unforeseen issues will predicably arise–but what they are, and when and how they will appear, is unknowable.

Use Both Linear and Systems-Based Safety Models

Linear-based (aka Safety-I) and systems-based (aka Safety-II) models of incident causation and prevention are based on different ideas of why incidents occur, and how the probability and severity of future mishaps may be minimized.

Both approaches have value, and in a complete risk management system, both approaches should be used.

A common mis-perception among individuals exposed to the ideas of Safety-I and Safety-II is that one is old-fashioned, obsolete, and should not be used, and the other is the shiny new model that ought to be adopted. Although even the subtitle of Hollnagel’s canonical text on the subject, Safety-I and Safety-II: The Past and Future of Safety Management, might lead one to such a conclusion, this is incorrect. In fact, both should be used—and the trick is to skillfully apply both models in the proper balance.

The benefit of using linear-based safety thinking

The linear-based understanding of safety presumes that incidents happen, from one or more usually identifiable causes. The task, then, is to find those causes, and prevent them from recurring. In this way, one prevents future incidents.

This method of risk management is useful, particularly in very simple incidents with relatively simple solutions—which may be the majority of incidents a risk manager experiences.

For instance, in the outdoor context, suppose that incident reports over several months show a trend of increasing incidents where hikers get uncomfortable itchy, blistering skin rashes due to an allergic response from contacting a plant such as poison oak or poison ivy (Toxicodendron spp.).

A linear-based response might be to add additional staff training about plant identification and avoidance, and add a clay (bentoquatam)-based blocker lotion and soap to the first aid kit.

Why is the poison oak growing more vigorously over the trail? Contributing factors could be many, and might include the global climate crisis, decreased land management agency trail maintenance budgets, or changes in hiker behavior.

It might not ever be possible to know which factors contributed and how much, and some causal factors may be difficult for an outdoor program to influence. However, even though the causes may be complex or unknown, the practical solution can be relatively simple.

The benefit of using systems-based safety thinking

The systems-informed understanding of safety recognizes that we may not know all the causes of an incident. And even if we do know some, we may not know exactly how to prevent them from influencing future outcomes.

Therefore, a sound approach is to build resilience into the organization, to reduce the probability and severity of incidents that will—likely inevitably, presuming the organization continues to exist—continue to occur.

This approach can help mitigate incidents not well-addressed by the more simple approach of the linear model of safety thinking.

In this way, Safety-II—systems-informed safety thinking—supplements Safety-I—linear-based safety thinking.

Safety-II does not replace Safety-I, but they complement each other in building a comprehensive risk management system well-equipped to deal with different types of risks.

Safety-II vocabulary

In Safety-I/Safety-II terminology, the Safety-II approach is framed as “don’t focus on what’s going wrong; focus on what’s going right.”

What this means is that just focusing on the causes of incidents and addressing those causes is not sufficient. Systems-informed safety thinking, after all, reminds us that incidents come about from emergent risks, or unanticipated combinations of risks.

Therefore, to successfully add the Safety-II approach to an organization accustomed to a Safety-I model, one should emphasize providing personnel with the skills, tools, values and other resources to successfully adapt to changing conditions—to emergent risks. When people use flexibility and creativity to adapt to these emergent risks, and thereby prevent incidents, that’s “what’s going right,” in Hollnagel’s terms.

Emphasizing the search for causes of past incidents—“what’s gone wrong”—and the elimination of those causes, is sometimes ineffective, in cases in which incidents spring from complex socio-technical systems, be they led outdoor activities, healthcare settings, aviation or otherwise.

In a comprehensive risk management system, the organization employs linear-based approaches to risk management, such as rules, checklists, and incident analysis. But the organization also uses systems-informed thinking, building an organization where things are mostly likely to go right. In Hollnagel’s terminology, this is a resilient system—one that maximizes “the ability to succeed under varying conditions.”

It’s not either-or: use both approaches

The importance of using both linear-based (Safety-I) and systems-based (Safety-II) models of risk management is clear. Provan et al. express this idea by saying that good risk management will “complement control with adaptability,” and in balancing the use of set structures and appropriate flexibility, “move between stability and flexibility as the context demands.”

Systems-Based Safety Thinking in Outdoor, Experiential, Wilderness, Travel and Adventure Programs

Let’s now look at how the ideas of linear-based safety thinking and systems-informed can be applied to the outdoor and experiential program context in a way that a provides practical and useable framework.

This application extends Hollnagel’s theoretical framework and includes additional elements, which can be applied to adventure, travel, wilderness and other types of outdoor and experiential programs.

The linear-based model of safety thinking reminds us that risks can be found in certain areas, such as poorly trained staff, defective equipment, and the like.

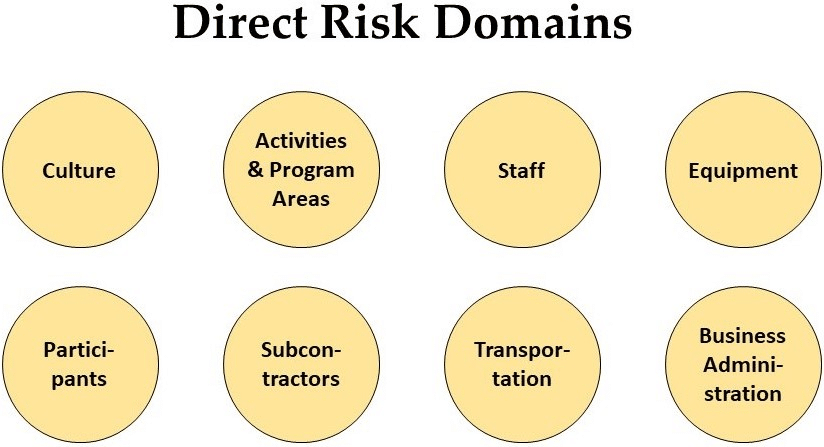

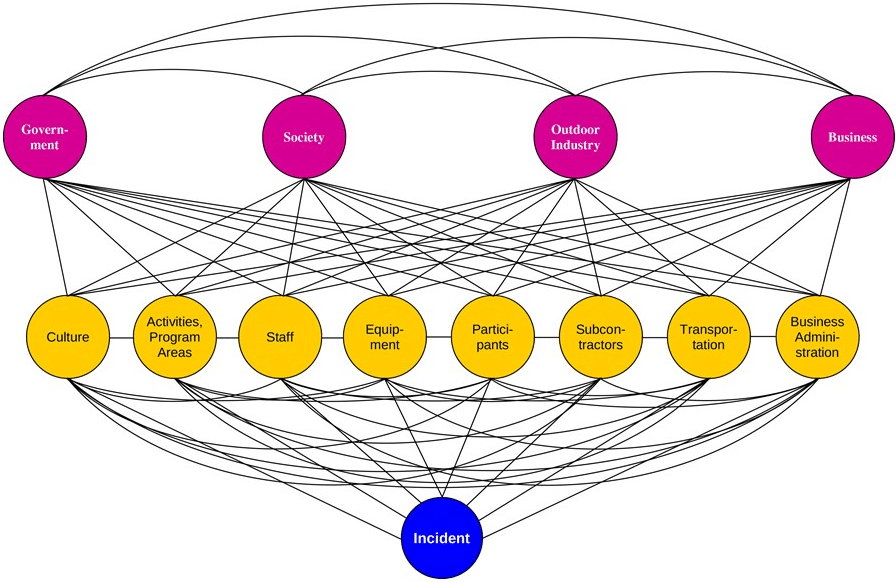

The Risk Domains model show eight areas, or domains, in which risks reside.

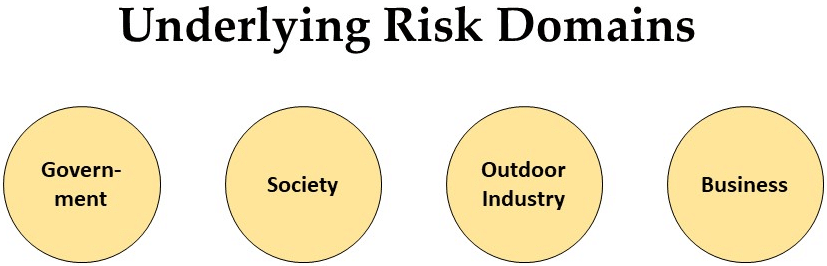

In addition to these eight “direct risk” domains, there are four underlying risk domains. These may indirectly affect risks, for example by influencing the regulatory environment or societal response to incidents.

However, a systems-based understanding of how incidents occur reminds us that incidents often happen due to multiple risks that combine in multiple unpredictable ways, leading to an incident.

The following illustration, then, shows the interconnections between risks in all domains, and how they may lead to an incident.

For example, a plane might crash due to a combination of inclement weather, equipment malfunction, and pilot error. Perhaps poor maintenance by ground crews, a global shortage of air traffic control agents, counterfeit components in the supply chain, and safety culture problems and shortcuts taken by the airplane manufacturer were also causes—these have all been cited as potential factors in recent airplane crashes, including those of the Boeing 737 MAX.

Although the image above shows the three components of the Risk Domains model—direct risk domains, underlying risk domains, and the network of interconnections between them and the incident—that network of causation is not always completely visible in real life.

Applying the Risk Domains Model

How, then, do we bring this model alive in managing risks of outdoor and experiential programs?

An organization performs a risk assessment (or, more accurately, multiple risk assessments, by different actors, on an ongoing basis) and identifies the risks that may reside in each risk domain for their particular organization, at least at that point in time.

The organization can then establish and maintain policies, procedures, values and systems in their organization, specific to the identified risks, to keep those risks at or below a socially acceptable level.

An example of a policy—an overarching, compulsory safety directive—might be, “a safety briefing is held prior to conducting each activity.”

An example of a procedure—the way something should be done, unless a clearly superior alternative exists—might be, “helmets and harnesses will be checked by a qualified staff member immediately before the participant begins rock climbing.”

An example of a value—something that is prized or held to be important—might be, “safety is important to us.”

An example of a system– a group of interconnected elements that work together as a whole—might be a medical screening system, or a staff training system.

Include Risk Management Instruments

In addition to applying policies, procedures, values and systems to manage specific risks that have been identified as existing at an organization at a certain point in time, certain broad-based tools, or instruments, which address risks in multiple or all risk domains, can be implemented.

Eleven risk management instruments are identified below:

Specific elements of these risk management instruments include liability insurance, emergency response plans, incident reports, press kits, and documentation of adequate training.

(There are many other models addressing risk management, including AcciMap and its variants. No model is perfect; by definition, no model represents the world, in all is complexity, exactly. All models have strengths and weaknesses, and risk managers can employ the models that work best for their particular context.)

So far, this Risk Domains model represents a linear approach to risk management: identify risks, and put in place policies, procedures, values and systems (elsewhere in the risk management literature, known as ‘barriers,’ ‘defenses,’ ‘mitigation measures’ or ‘controls’) to reduce those risks to a socially acceptable level. But the last risk management instrument introduces an additional way of approaching the management of these—and as yet unidentified—risks.

The last risk management instrument is “Seeing Systems.” This means applying systems thinking to management of risks. This is where the interconnections—in the Risk Domains illustration, the web of lines between each risk domain and the incident, some of which in real life are evident, some of which are invisible—are addressed. Here is where we expand from the linear-based (“Safety-I”) model to also incorporate a systems-informed (“Safety-II”) approach.

Three Techniques for Applying Systems Thinking to Outdoor Risk Management

We recognize that our organization may encounter multiple risks, in the eight direct and four underlying risk domains illustrated above.

But in order to effectively manage risks, we have to recognize that, in a complex system:

- New risks may unexpectedly appear—“emergent risks”

- Risks may combine, in ways that we can’t always see, understand, predict or control, to lead to an incident

- Therefore, we should not expect it to be possible to prevent all incidents from occurring

How then, to be best prevent mishaps from occurring, given the limits we face in managing or even understanding the elements of a complex socio-technical system?

Three ways to apply systems thinking to managing the risks of outdoor and experiential program include:

- Resilience Engineering

- All-Domain Consideration

- Systems-Informed Strategic Planning

Let’s look at each of these three strategies, in turn.

Resilience Engineering

Systems thinking tells us we can’t always anticipate what the next incident will be, which risk factors will be involved, or when it will occur. As a consequence, we must anticipate that at some point, an incident will happen.

The principle of resilience engineering, then, encourages us to create within our organization the ability to withstand perturbations to the system without substantial loss of functionality.

This means building in to our operational systems a margin for error. We expect a breakdown in the system, from an unknown location (staff, equipment, vendors, culture, etc., or a combination). And we build a system that can accommodate that error, and still allow the larger organization to function.

What does that look like specifically, for an outdoor or experiential program? Four approaches that can create resilience are:

- Extra Capacity

- Redundancy

- Integrated Safety Culture

- Psychological Resilience

Extra Capacity

The first aspect of resilience engineering we’ll discuss is extra capacity.

Have additional resources that can be called upon in a time of need can build resilience, creating a buffer that reduces the probability of a serious incident. This could include periods of increased demand or reduced supply. Examples of such resources include:

- Additional field staff, suitably trained and available, that can be called upon in case of sudden illness of an activity leader

- Extra equipment on hand, in case a participant arrives without adequate gear, or items are lost or damaged

- Staff trained at a higher level than required: for example, a person trained to run class IV whitewater might be restricted to leading class III or lower water, to be able to skillfully respond in case of emergency

- Emergency response staff on call at headquarters, to mount an in-house search and rescue operation before SAR teams respond

- Telecom access to extra support, such as satellite phones in the field to access medical, rescue and other resources

- Cash cushion, so the organization can weather a crisis (such as a fatality or a pandemic) without facing an existential financial threat

However, having backup resources involves a delicate balance: spending too much on reserve capacity can create inefficiencies, and limit or cripple an organization’s competitiveness and ability to grow.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, government officials were criticized when emergency stockpiles didn’t have sufficient masks, ventilators, and other pandemic response materials. But those same politicians get criticized during pandemic-free times for spending money on unused medical response supplies when there isn’t a pandemic.

Investigators cited a lack of staffing and other resources as contributing factors in the Mangatepopo Gorge tragedy.

Redundancy

The second aspect of resilience engineering is redundancy.

In systems-informed safety, we know that a system component will fail. We just don’t know which one or ones, and when, or how.

Having backups helps ensure that when one system component doesn’t work as well as it might, a reserve component can fill right in.

An example is having multiple ways to identify emerging safety issues. An outdoor program could identify potential new risks through program debriefs by activity leaders, completion of incident reports, holding periodic internal and external risk management reviews, and formally soliciting participant feedback by standard evaluation mechanisms like post-program feedback forms.

Requiring two field staff persons, both with suitable training and certifications, is another example of redundancy.

In aviation, multiple pilots, flight computers and engines are examples of the redundancy principle in action.

Integrated Safety Culture

Third, an essential component of resilience engineering is the presence of an integrated safety culture.

We use that term here to mean the integration of policy and procedure on the one hand, and supporting individuals to use their own good judgment to make decisions, on the other.

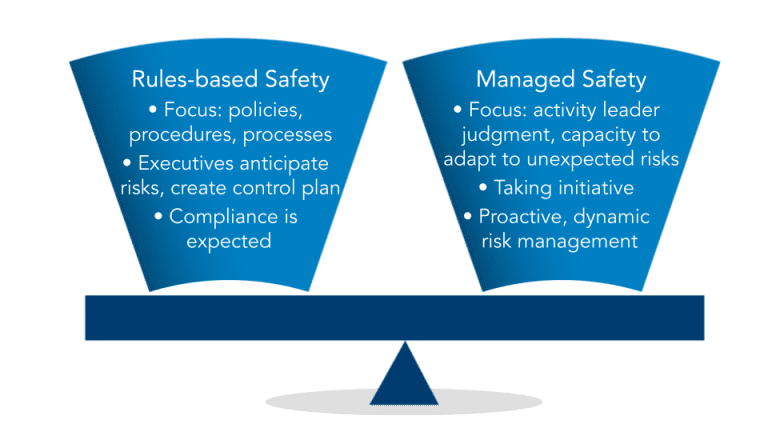

These two approaches are called “rules-based safety,” where adherence to policy and procedure established by management is emphasized, and “managed safety,” where activity leaders can manage emerging situations according to their good judgment, flexibly adapting to unexpected situations.

Engaging in “dynamic risk management,” where a person continually and proactively scans the environment for risks, and takes remedial action in the moment, is another element of managed safety.

You may observe, correctly, that “rules-based safety” reflects the linear-based approach of Safety-I, and “managed safety” in this context reflects the systems-informed approach of Safety-II.

The use of policies—which should generally always be followed—and procedures, which may be altered if doing so is clearly superior—is an example of building in an integrated safety culture.

Providing training in judgment and decision-making, and discussing during that training when use of judgment to over-rule procedure is and is not appropriate, is another example of fostering an integrated safety culture.

A brief aside to mention integrated safety culture and parallels to education philosophy. One analogy in the risk management Safety-I/Safety-II literature that may be of interest to experiential educators is the comparison of rules-based safety and managed safety to a lecture-based educator and a facilitation-based educator:

An old-style “chalk talk” teacher gets up in front of the class, and gives their lecture. In the learning process, the teacher is the source of wisdom, and students receive the wisdom.

In experiential education, the facilitator creates conditions for the learner to learn. The learner draws their own meaning from the experience that they co-create, guided by the facilitator. The learner is actively engaged in the learning process and is responsible for taking initiative, making decisions, and constructing meaning.

Here we see that the lecture-only teacher rigidly imposes their idea of what the student must learn—similar to management that insists that the safety rules they establish must be followed.

And the experiential educator guides, continually adapts to circumstances, and continually changes their approach depending on how the learner is responding to the learning environment and activities.

Provan sums up the risk manager, as in any given moment, they select a Safety-I or Safety-II approach, by asking, “Are they the controller, or are they the guide?”

We must remember that both approaches are essential. There is a role for rules and structure, as in Safety-I, and space must be made for flexible decision-making, as in Safety-II. This is just as there is a role for the lecture presenter, who can transmit large amounts of important information in a short amount of time, and the experiential educator, who can support learners to create long-lasting learning and deep meaning through guided exploration.

Integrated safety culture maximizes the benefits of both rules-based safety and judgment.

Psychological Resilience

Fourth, and finally, comes the role of psychological resilience in resilience engineering.

This has to do with resilience as a way of thinking, and a way of responding to stress. A psychologically resilient individual has values, motivations and skills to be creative and adaptable in the face of uncertainty and challenge. They may even have a positive attitude towards challenge, seeing it not as an uncomfortable and unwelcome threat to their security and stability, but as an opportunity for them to show their skill and leadership in a time of need, and make a real difference.

In 2006, during a large wildfire that scorched tens of thousands of acres in California USA, the 335-acre campus of an outdoor education center burned down. The staff house, with the personal possessions of 19 educators, turned to an 18-inch pile of ash. The office, with its 35 years of records, was left in cinders.

The outdoor education program sought to instill courage and perseverance in its program participants through overcoming wilderness challenges as a team. The leadership of the organization, in turn, saw the destruction of their physical premises as, in some ways, the challenge they had been waiting for: an opportunity to show real leadership, and depth of character, and the treasured opportunity, through re-building the organization, to accomplish great things.

When organizations and individuals can foster a culture that values facing and overcoming challenges, together, the likelihood of successfully managing critical incidents is increased.

All-Domain Considerations

A second way by which outdoor programs can apply systems thinking to safety management is through intentional consideration of all risk domains.

Direct Risk Domains

When managing risk, all eight direct risk domains—culture, activities & program areas, staff, equipment, participants, subcontractors, transportation, and business administration—should be considered.

For example, when beginning operations a new program area or offering a new type of activity, systems-informed risk managers should avoid simply filling out a risk register in order to think about direct risks of that activity or area, and considering that the primary risk management tool.

If considering a caving trip, for instance, the risk assessment might look at direct risks of the activity, such as hitting one’s head. It might look at risks of the location, such as if the cave is known to flood.

Risk assessments (also known as risk registers) have their place, and they can be useful when planning for new activities, participant populations, or program areas. But they are not enough. Risks in all the domains should be assessed to evaluate the potential new activity.

Will we overwhelm our Human Resources department staff and systems in attempting to hire and train new activity leaders for this new program? Is the business office able to generate accurate marketing materials and appropriately written risk acknowledgement forms? Do logistics staff know where and how to acquire and manage the new equipment? Are there authoritative, well-developed standards to help us institute appropriate activity procedures?

Indirect Risk Domains

In addition to the direct risk domains, indirect risk domains should be considered. These are government, society, outdoor industry, and business.

The absence of government regulation may lead to incidents, as we saw in the Rip Swing incident described earlier. Conversely, the presence of outdoor safety regulation and legislation may improve safety across the board, as seen in the UK and New Zealand.

A society that doesn’t place a high value on personal life—particularly lives of disenfranchised groups like racial or religious minorities, and non-citizens—can increase the probability that dangerous conditions go unaddressed. A society that does place a high value on human life may be more successful in pushing for systemic safety improvements—as was seen in the aftermath of the 1993 Lyme Bay kayaking incident in the UK.

When organizations and associations in the outdoor and experiential fields come together to create safety standards, and support safety legislation, everyone can benefit.

Finally, when large and powerful corporations feel a sense of social responsibility, rather than relentlessly pushing to reduce regulation and the capacity of the government to enforce safety rules, all aspects of society—including outdoor programs and their participants—can see improved safety outcomes.

Just Culture

The idea of just culture is to look for the underlying factors that led to an incident, rather than reflexively blame the person closest to the incident.

This brings the concept of systems thinking to the human resources sector, particularly with regards to discipline procedures, accident investigation, the quality assurance process, and incident reporting.

If an outdoor activity leader makes an honest mistake—for example, momentarily failing to pay attention while belaying a rock climber, who falls and injures their ankle—some might discipline or fire the activity leader.

Just culture asks us to look deeper. Did management create an exhausting program schedule that led to a fatigued staff person? Did staffing problems lead to the belayer having to supervise too many things at once? In a just culture, these contributing factors can be brought to light and addressed. This leads to actually addressing the real causes of the incident, improving safety.

Systems-Informed Strategic Planning

The third and final way we’ll look at for outdoor programs to apply systems-informed risk management is by employing systems-thinking strategic planning techniques.

Some risk management planning is retrospective, and constrained to incidents that have already occurred. An example is the systematic review of incident reports, individually and in the aggregate. Doing so is good practice, and should not be neglected. But incident report analysis does not generally do a good job of preventing future incidents from novel combinations of causes.

One technique for thinking more broadly about emergent or under-appreciated risks is by visualizing a catastrophe that happens at the outdoor organization, and then brainstorming ideas on how this hypothetical incident might have occurred.

Called a “pre-mortem,” this process helps individuals think creatively and generatively about risks that might be known, but have not been affirmatively addressed.

After a fatal accident at one outdoor program, in which a field instructor lost their life, the CEO convened a group of instructors to lead them through this “visualizing catastrophe” exercise. The CEO asked, “Who is the next person who is going to die here? And how will they die?”

The activity leaders were able to articulate some nagging concerns and subtle, difficult-to-address issues—including long hours, heavy workload and high turnover—that could be contributing factors to the next fatality, and which then could be the focus of renewed effort to address.

In Conclusion

From Confusion to Clarity

The Safety-I/Safety-II concept has been a source of confusion for many. Often described in abstract conceptual terms, Safety-I and Safety II, Provan notes, is “a safety theory that has proved difficult to translate into practice.”

Provan goes on to say Safety-I/Safety-II is one of many “idealised and often apparently contradictory ideas about how safety should be managed.”

Aspects of the multitudinous safety theories (including Safety-I/Safety-II) in circulation have been mis-represented and misunderstood by theorists and practitioners.

It’s hoped that the descriptions of Safety-I and Safety-II here provide some clarity, especially for practitioners and managers of outdoor, experiential, wilderness, travel and adventure programs.

In Summary

We began by describing Safety-I and Safety-II as expressions of linear-based safety thinking (Safety-I), and systems-informed safety thinking (Safety-II).

We recognized that both are important; both have a role to play, and individuals should employ both approaches in managing risks.

In a linear-based safety model, risk assessments identify risks in all 12 risk domains (such as safety culture, transportation, and subcontractors). Policies, procedures, values and systems are then established and sustained to reduce these specifically identified risks to socially acceptable levels. In addition, broad risk management instruments, such as insurance and incident reviews, are employed to manage risks across multiple or all domains.

Systems-informed risk management excels at addressing emerging risks, or novel risk combinations, of which one may not be aware.

Here we use resilience engineering, consideration of all risk domains, and systems-informed strategic planning to manage risks.

Resilience engineering involves having extra resources available, employing redundancy or back-ups, sustaining an integrated safety culture that balances rules-based safety with individual judgement, and fostering psychological resilience in personnel.

All-domain consideration involves looking at risks in all direct risk domains and underlying risk domains. Specific applications include when planning for a new activity or a new program area, or for working with a new participant population, and in employing just culture following an incident.

Systems-informed strategic planning involves using techniques that support creativity in considering emergent or under-appreciated risks. Visualizing catastrophe, or the “pre-mortem,” technique, is an example of systems-informed strategic planning.

To Learn More

Hollnagel’s text, Safety-I and Safety-II, is the source document for Safety-I and Safety-II concepts.

The book may be a particularly good fit for those interested to travel with Hollnagel on multiple intellectual discursions (for example, on stochastic resonance, hermeneutics, ontology, combinatorics, and exogenic performance variability), and who seek a text not outdoor-specific but providing a sweeping intellectual overview of the Safety-I/Safety-II concept.

Individuals interested to continue exploring ideas and applications of systems thinking and risk management, specific to outdoor and experiential programs, will find a treatment of that topic, including material presented above, in the text Risk Management for Outdoor Programs: A Guide to Safety in Outdoor Education, Recreation and Adventure.

The opportunity to explore a comprehensive set of topics regarding safety and outdoor/experiential activities, and consider their application to one’s own program, comes in the 40-hour online course, Risk Management for Outdoor Programs. This training covers systems theory in outdoor programs, as well as a full suite of other topics, and guides participants in how to apply the material to improve safety at their own organization.