The government of Singapore has released a draft of new standards to support safety in Outdoor Adventure Education activities across the country. Stakeholders are invited to comment on the draft standards before a final version is published.

Safety in outdoor adventure learning activities in Singapore became a concern following a 2020 incident in which a nine-year-old-girl fell from a zipline, resulting in a jail sentence for the zipline facilitator.

Concern was increased when the next year, a 15-year-old boy fell and died on a high ropes challenge course element, resulting in another facilitator being sentenced to jail.

After these incidents, high elements activities in Singapore were restricted for two years, pending the development of strict new high elements safety requirements.

To improve safety outcomes across the adventurous activities sector in Singapore, a National Outdoor Adventure Education Council was formed, and charged with developing comprehensive standards for outdoor adventure learning activities across the nation.

The standards development process began in 2022.

The official draft Singapore Standard was prepared by the Working Group on Outdoor Adventure Education set up by the Technical Committee on Personal Safety and Health under the purview of the Safety and Quality Standards Committee of the Singapore Standards Council, which is administered by Enterprise Singapore, an agency of the Singapore government.

The group that drafted the standards is composed of a mix of government specialists from the Ministry of Education, Outward Bound Singapore (part of the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth), other government agencies, and representatives of the outdoor adventure learning private sector, including Singapore’s Outdoor Learning & Adventure Education Association.

Enterprise Singapore, which is in charge of the official national standards development process in Singapore, has issued a call for public comments on the draft standards.

The Notification of Draft Singapore Standards describes the proposed standard as follows:

Management systems for outdoor adventure education (OAE) activities

This standard provides a framework and describes best practices which can be used for creating or revising OAE activity programmes while highlighting the unique safety requirements for the most common outdoor adventure activity types used for educational purposes in Singapore.

Users of the standard include academic institutions, OAE providers, programme supervisors,

activity leaders, guides, instructors, trainers, safety managers, testing, inspection and certification (TIC) bodies and relevant government agencies.

The comment period runs until August 15. Once the draft is finalized, it will become an official Singapore Standard.

The draft “Management systems for outdoor adventure education (OAE) activities” Standard is available for viewing by relevant stakeholders online.

What Does the Outdoor Adventure Education Activities Management Systems Standard Contain?

The draft standard is written in the typical format used by national and international consensus standards publication bodies, and includes sections covering scope, normative references (such as ANSI/ACCT 03-2019, EN 12277, NFPA 1983, and UIAA 105), terms and definitions, and core planning principles.

In good technical writing style, the standard distinguishes between various levels of compulsory, recommended and suggested action, noting:

- “shall” indicates that the requirement is strictly to be followed in order to conform to the standard and from which no deviation is permitted;

- “should” indicates a recommendation;

- “may” indicates a permission;

- “can” indicates a possibility or capacity.

The document notes, “this standard helps providers of OAE programmes to develop appropriately managed educational adventure activities for individuals and our communities, while protecting the environment and culturally significant places.”

The standard has sections addressing various outdoor adventure education activities common in Singapore:

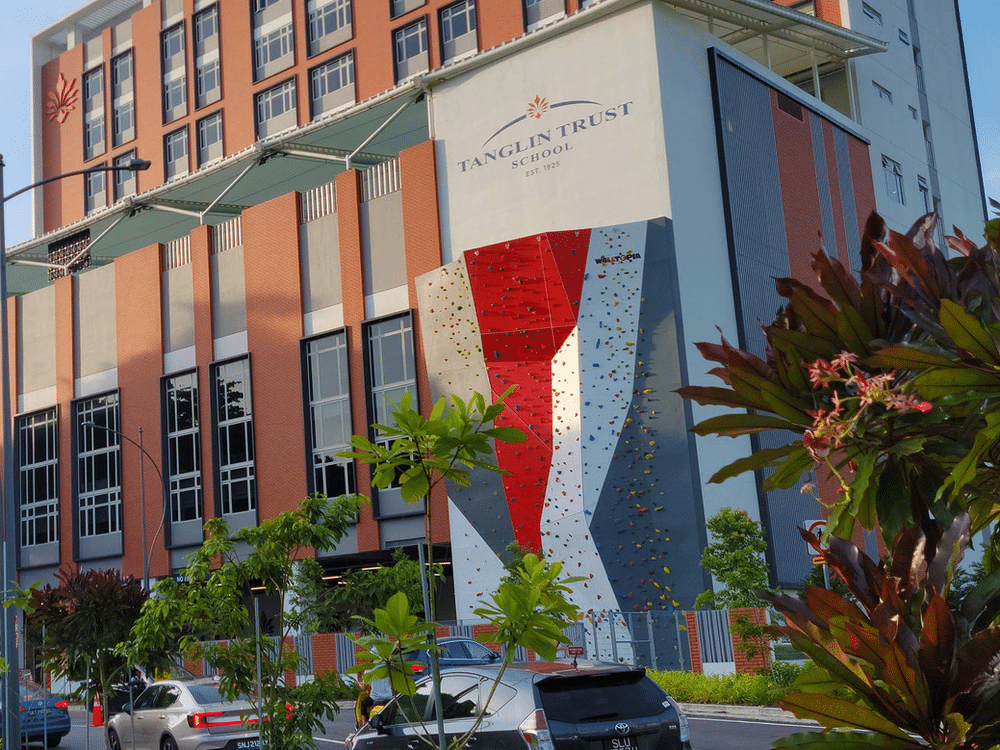

- Abseiling and climbing

- Challenge course (low and high)

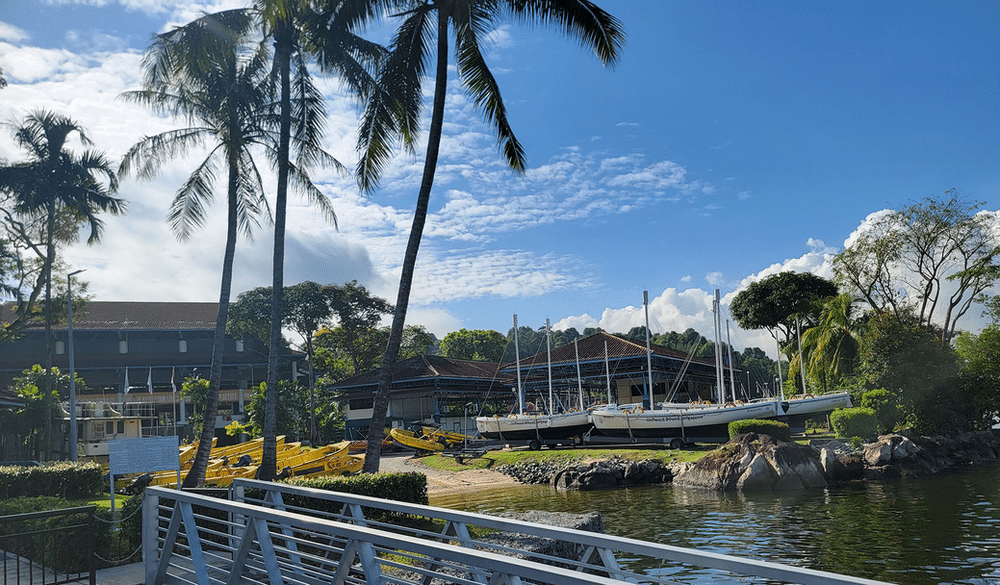

- Watercraft paddling and rowing

- Improvised rafting

- Walking, hiking and navigation-based activities

- Camping

- Experiential learning initiatives and games (ELIG)

The draft also includes five Annexes, covering:

- Medical conditions to factor into risk management

- Environment sustainability procedures

- First aid kit types

- Pathways for recognition of activity leader and assistant activity leader competence

- Safety support of improvised rafting in different open water environments

Programme Planning

The document describes “programme planning” as a core planning principle, done at both the programme and activity level.

The activity plan framework is to be based broadly on the type and intent of the activity, then be expanded to include activity-specific details.

The standard requires providers to include a documented risk management plan in all their OAE programs, and briefly notes the plan shall factor in all involved parties, including the provider, activity leadership, responsible persons, participants, client organizations, and parents and legal guardians.

The standard does not provide an in-depth discussion of considerations from all levels of the complex sociotechnical system that is the Led Outdoor Activities sector (such as the role of government regulation or industry accreditation schemes), but references a framework associated with ISO 31000 on risk management.

Emergency Management

The standard requires providers to have an emergency management plan, including standard operating procedures (SOPs) for first aid, evacuation, internal communication to staff, and external communications to the authorities, media, and other relevant stakeholders.

Importantly, the standard requires providers to ensure all responsible persons are familiar with the plan and their role in it, and requires the plan to be regularly tested and evaluated.

Incident Reporting

The standard requires providers to implement an incident reporting system. Providers must ensure the system is used correctly, ensure data is analyzed individually and collectively, and review risk management and activity plans in light of the incident data.

Participants

Under the draft standard, providers must provide a comprehensive introduction to each OAE activity prior to a participant agreeing to take part in a programme. This is to help the potential participant and their parents/legal guardians make an informed decision regarding participation.

The pre-programme communication should include information on foreseeable risks and a summary of risk management strategies, among other topics.

Providers must request information from clients, intended participants or their legal guardians, which can include health history, a signed acknowledgement of risk, and a consent to receive medical treatment.

The draft discusses inclusion, noting that areas addressed in discrimination policies and procedures can include gender identity, sexual orientation, race, and disability awareness, among others. (The encouragement to support inclusion with respect to subjects such as gender identity is commendable and notable, given Singapore’s relatively conservative culture.)

Activity leaders must provide “a thorough briefing” to participants, to include clear safety instructions, expected participant behaviour, and other topics.

Learning Design, Facilitation and Environmental Considerations

Although its focus is safety, the plan also addresses how to minimize environmental impact and principles of learning design. A learning design process is illustrated, and an instructional plan is required, which must include sequencing activities based on a learning needs analysis, learning objectives, instructional methods, and a contingency plan, among other components.

The standard also requires OAE providers to develop facilitation plans which must include a set of ethics, promoting a “minimum impact” approach, and conflict management. The standard notes that framing of experience, participant reflection, and transference of learning can be employed.

Providers must include SOPs which address environmental sustainability.

Activity Leader Competence

The standard discusses pathways for recognition of activity leader and assistant activity leader competence. This is noteworthy, as long lists of good practice guidelines are less helpful without a sufficient number of qualified activity leaders to skillfully implement them. A well-developed system for training and credentialing such leaders is essential to building this corps of capable personnel.

This has been a significant issue in Singapore in the last few years, as many professionals in the country’s relatively small experiential education sector left the industry during the pandemic for other fields, as health and safety restrictions diminished OAE operations for years.

The document addresses recognition by Singapore governing bodies such as the OAE Council, outdoor sector bodies and national sports associations; governing body-approved training, and qualified peer verification.

Activity-Specific Requirements

The draft standard provides detailed activity-specific guidelines, which include extensive tables and figures describing roles and responsibilities, supervision requirements, supervision hierarchies, and more.

The bulk of the standard is devoted to addressing these activity-specific procedures.

These provide granular-level detail on a numerous parameters, such as:

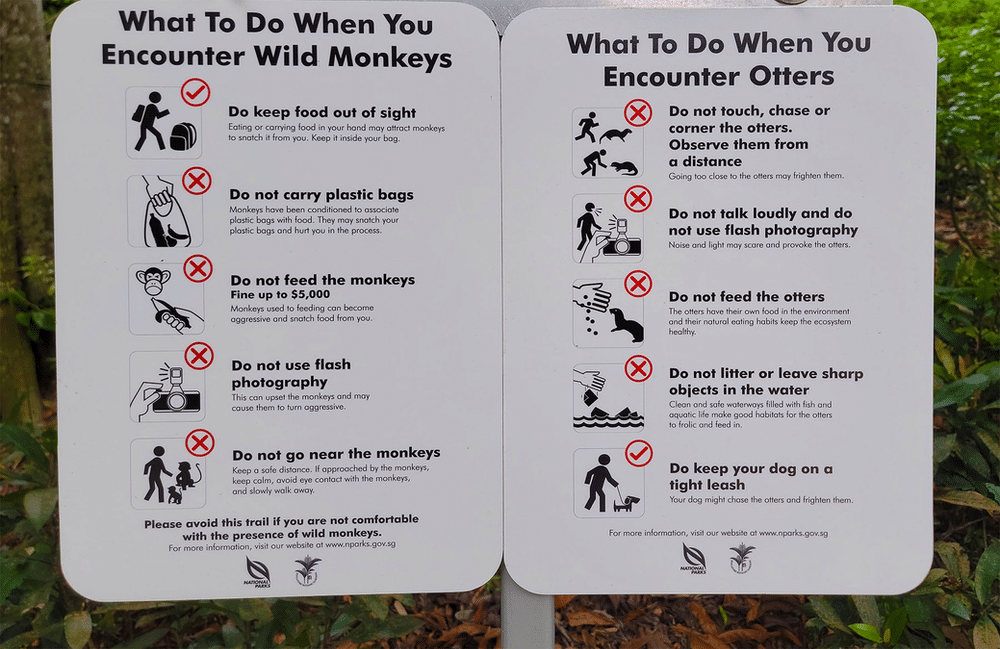

- The provider should address confrontations with troops of monkeys and otter families

- Communications equipment specified includes ultra-high frequency radio transceiver and trunked radio

- The use of GPS tracking devices to monitor participants’ progress

- PFDs that are at least ISO 12402-5 or United States Coast Guard approved Type III certified

- Different supervision types during raft beaching and during raft disassembly

- Typical group first aid kit items, including individually wrapped sterile adhesive dressings, petroleum jelly and foldable stretcher

- Licenses and safety competencies for improvised rafting in different open water environments

- Procedures to minimise/mitigate risks of sleepwalking

For example, section 5.7.4 on ‘Abseiling and climbing – Equipment and logistics – Rescue equipment’ specifies:

Rescue equipment including specialist vertical rescue equipment shall be readily accessible. Vertical rescue equipment should include but is not limited to:

- ascending devices;

- belay device;

- connectors;

- knife;

- pulleys;

- prusik loops;

- rope long enough for the longest pitch (applies to abseiling only); and

- slings.

This level of detail is similar to that of the Good Practice Guides that are part of the Australian Adventure Activity Standard and associated Good Practice Guides.

It is also similar to the level of detail in New Zealand’s Activity Safety Guidelines (for activities covered by Adventure Activities Regulations) and Good Practice Guides (for activities not covered by Adventure Activities Regulations).

The extensive detail over 132 pages exceeds the specificity of the Standards of Industry Practices published by Singapore’s Outdoor Learning and Adventure Education Association, which were industry-leading at the time of their publication in 2018. (Members of the team that developed the OLAE standards also were part of the Working Group developing the Singapore Standard.)

They also exceed the level of detail in the 101-page Outdoor Adventure Learning Activity Guide for MOE Schools, published in 2019 by the Ministry of Education, although that Activity Guide is noted for its extensive and well-developed safety specifications.

Observations

The 132-page document is notable for the admirable level of detail it devotes to explaining what constitutes good practice for adventure activities safety. It ranks as one of the most detailed documents available on the subject, in this regard.

Many national/international standards are substantially shorter, to wit:

- ISO 21101:2014 – Adventure tourism — Safety management systems — Requirements (30 pages, including front and end matter)

- ISO 13289:2011 – Recreational diving services — Requirements for the conduct of snorkelling excursions (9 pages)

- BS 8848:2014 – Specification for the provision of visits, fieldwork, expeditions and adventurous activities outside the United Kingdom (48 pages)

(The Accreditation Process Guide of the American Camp Association exceeds 200 pages, however, and the Safety Guidelines for adventure activities in Maharashtra, India clock in at 267 pages of exquisite detail.)

The document also far exceeds the 34-page Safety Management System Requirements for Adventure Activity Operators resource used in New Zealand’s adventure sector.

The draft Singapore standard doesn’t seem to have a clear parallel in the global assembly of adventure safety standards, as it attempts to do almost everything—cover pedagogy, environmental impact, and risk management, for all common adventure activities on land, sea or in the air, across an entire nation—in a singular consensus standard.

The standard is a draft, however, and when published will be version 1.0. It may be that in the years and decades ahead, the standard is broken into individual activity-specific documents, as in the case in New Zealand and Australia, and as seen with separate ISO standards for scuba diving, snorkeling, and other activities.

Clearly the document represents a massive investment of intellectual capital over recent years across Singapore’s outdoor adventure education sector, widely respected as one of the best in the world. It builds on years of work on similar standards—from MOE, OLAE and others—across the nation. And it is poised to provide a new depth of valuable guidance and support for the OAE sector in Singapore and beyond.

Viristar’s Involvement

Viristar did not have a formal role in the development of the standard, but had multiple discussions with government and private sector representatives involved in writing the draft, as the document was being developed.

A number of members of the Working Group on Outdoor Adventure Education which drafted the Standard—from both the government and private sector—are graduates of Viristar’s Risk Management for Outdoor Programs training.

Conformance is Voluntary

Safety requirements are normally more effective than voluntary safety standards. However, compliance with the Singapore standard is expected to be voluntary.

Why diminish the efficacy of this painstakingly developed document by allowing adventure providers to fail to meet its criteria?

One Singapore government official noted that the private sector preferred that conformance with the standards be optional, due to concerns about whether compulsory regulations would be too burdensome, relative to their benefits.

Who Will Meet the Standard—and At What Cost?

The 132-page standard is bristling with detailed requirements for planning, training, documentation, and more.

Is it realistic for small providers to meet this massive and exacting standard?

Many smaller providers may find it difficult to conform to the extensive criteria in the document.

Should there be pressure—in the form of social expectation or government requirement—to meet the standard, this may result in consolidation in the sector, as smaller providers with limited capacity and marginal finances decide it’s unrealistic to meet the standard’s requirements.

This occurred in the UK in the 1990s, as the government instituted adventure safety requirements, and a substantial number of smaller adventure providers decided to cease operations.

An expectation to meet the standard may also represent a barrier to entry in the sector.

However, these consequences may not be viewed as negative, over the long term and from the macroeconomic perspective.

Ultimately, expectations to meet high standards for quality and safety should serve to advance professionalization of the outdoor adventure education sector. This will reward businesses who invest in quality, enhance the reputation of the sector, and improve outcomes for participants.

One can trace the development of the pharmaceutical industry from a sector characterized by ill-trained chemists and hucksters grinding up and pressing chemicals into pills of dubious efficacy, in centuries past, to the current day, where in high-income countries the pharmaceutical sector is a highly regulated industry characterized by the presence a small handful of large corporations, and consistently safe and effective products. This undoubtedly represents a positive advancement overall, in the evolution of the medical sector.

While adventure education and pharmaceuticals are very different industries, one can see that the establishment of safety and quality standards can be, in the big picture, good for business, and good for the public at large.

But doing this well is a team effort, and continued government engagement with the adventure sector is needed to ensure that adventure-based learning providers—especially smaller ones—have the capacity to meet ever-increasing expectations.

It’s important, consequently, for there to be continued robust financial and operational support from the government to build the capacity of industry associations and governing bodies to provide training, certification, accreditation schemes and continuing professional development opportunities the OAE sector will need to continue to grow and improve.

Tools Are Only As Useful As Their Application

Standards documents are tools, and like other tools, they are most useful when used in the appropriate way, at appropriate times, in appropriate circumstances.

What remains to be seen, then, is:

- How many outdoor adventure education providers in Singapore seek to meet the standard

- Whether providers fully or partially meet the standard

- Whether other elements to support safety—such as relevant regulation, accreditation schemes, qualifications (activity-leader certification) schemes, government support for the sector, and governing bodies—become or remain as well-developed as the standard

In Switzerland, for example, after 21 people drowned in a canyon flash flood, a “Safety in Adventure” voluntary scheme was developed. As it was optional, however, few providers bothered to meet the standard.

Over the next 10 years, safety incidents continued, and the voluntary system was scrapped, with a safety law for adventure activities put in its place.

The Association for Experiential Education has a well-developed standard for experiential adventure activities, including detailed risk management criteria, and a comprehensive accreditation scheme to verify conformance with the standard. However, after decades of making the voluntary accreditation option available, fewer than 60 operators worldwide are currently accredited. Without a robust incentive structure, AEE’s high-quality adventure safety scheme is under-utilized.

But even the establishment of compulsory requirements is no guarantee of widespread adoption. In Maharashtra India, after more than a decade of development, requirements for adventure tourism safety were instituted by the government in 2021. However, due to a variety of factors, the regulations, and the safety systems they envisioned, have never been fully implemented.

Next Steps

The Singapore government invites comments on the proposed Standard, and a final standard may be issued by the end of the year.

The private OAE sector has been deeply involved in leading the development of the standard, and is presumably invested in its application, knowing that a high-quality and well-run sector better supports business sustainability than one that doesn’t enjoy good safety outcomes.

Australia has had a nation-wide, voluntary Adventure Activity Standard for some years. A handful of industry leaders in Australia are encouraging the development of an accreditation scheme that would involve an independent audit to determine if an operator meets the standard. Those that show evidence of conformity would then be awarded an accreditation badge, which can help assure the public that good practices are in place.

Some outdoor adventure sector leaders envision this accreditation scheme eventually being replaced with a compulsory, regulatory system, where conformance to good adventure safety practice is required.

The perils of self-regulation are well-known.

However, the idea of instituting an accreditation system or regulatory requirement to improve safety in the Australian adventure sector is experiencing resistance from parts of the private sector as well as the government, which is reluctant to regulate business unless there is a clear danger to the economy.

However, before visions of accreditation or regulation can come to fruition, it will be a great accomplishment simply to publish a complete, well-developed consensus standard on management systems for outdoor adventure education activities in Singapore.

Conclusion

The development of the draft standard for management systems for outdoor adventure education (OAE) activities is a monumental achievement, and illuminates the dedication of the Singaporean government and industry to helping Singaporeans develop resilience, team skills and character through well-run outdoor adventure activities.

The comment period through this August offers an opportunity for all those connected to the Singapore OAE sector to provide additional ideas to improve the standard.

Singapore is a global leader in its commitment to bringing the benefits of outdoor adventures to the people of Singapore and beyond. The development and eventual implementation of this standard represents another opportunity for the country to be a role model to the world.