What3words and Google Maps Find Both Support and Criticism

The three young hikers were getting closer to the river, as they navigated down the steep terrain and patches of tricky, loose surface with their heavy packs. It was a hot day—about 36 degrees C (97 F)—and very dry, in Australia’s Blue Mountains National Park.

The hikers, a trio of teenage boys on a Duke of Edinburgh Adventurous Journey, needed water.

They had started their three-day backpacking trip the day before in the town of Katoomba, and hiked to a campsite where they expected to find water—but the creek there was dry.

Now, hiking towards the Kedumba River on the trail from Mt. Solitary, things were getting desperate.

David, the fittest of the three boys, ran ahead. But then he veered off the trail, and his companions passed him by. At this point, he had been 17 hours without water.

He pulled out his cell phone and called the emergency number in Australia, 000. Excerpts from the call transcripts illustrate the conversation:

David: Hi, this is an emergency. I have been walking the Mt Solitary track and I am near Kedumba River and yeah, that’s all I know.

Operator: Do you know where you are?

David: No.

Operator: The Mt Solitary walking track may not be on a map. You need to tell me what the nearest street you know is that you’ve gone past is. Okay?

The call then dropped.

David called back.

Operator: Ambulance emergency, what suburb please?

David: I’m lost, I need water, I haven’t had water for a long period of time …

[caller yelling].

[operator cuts over caller]

Operator: Sir, do you need an ambulance there?

David: Yes

Operator: What suburb are you in?

David: I’m in Katoomba …

Operator: Where in Katoomba are you, sir?

David: I’m not in Katoomba, I set out from Katoomba

Operator: Okay, so where are you now?

David: I am on the walk from Katoomba, actually not from Katoomba, the Mt Solitary walk, Mt Solitary walk, I’m going down to the Kedumba River on that walk

Operator: Okay, it’s near the Kedumba River. Okay do you know what street you might have started on when you were in Katoomba?

David: Hello? [caller yelling]

Operator: Hello? Hello?

The call dropped again.

David placed another call, and another. Despite David describing his location on a trail in a national park, emergency operators kept asking for a street address.

David, dying of thirst, called emergency services seven times. Operators never did figure out how to determine his specific location.

David’s body, leaning against a tree in a rocky, dry gully, was found by searchers, eight days later.

Questions of Location-Identifying Technology

In the investigation that followed, the coroner criticized the “relentless focus” of operators on attempting to obtain a street address or precise location from David, when it was obvious that he was lost in bushland.

The coroner called the preoccupation with getting an address “astounding,” and recommended numerous changes to the operation of emergency services.

(The investigative report also made a number of other recommendations—for example, despite the group having been provided with maps and an “Excursion Risk Management Plan,” improved safety and supervision policies were suggested. It also recommended that the Minister for Environment and Climate Change review whether park users were provided sufficient information about safe water consumption. In a changing climate, water sources that once were dependably available are no longer reliable. Here, however, we’ll just consider location-finding implications of the tragic incident.)

David’s untimely death occurred in 2006. Since then, electronic technology for identifying locations has changed. Yet the question remains: what is an optimal method for quickly determining a person’s location, in the wilderness, to facilitate prompt arrival of emergency services?

what3words: admired by some; reviled by others

One tool in the quest to reliably and accurately identify a person’s location in the wilderness is the location reference system what3words, which launched in 2013.

What3words divides the world into a grid of 57 trillion squares, ten feet on a side. Each square is assigned a unique three-word label.

For instance, the top of Mt. Everest in Nepal is “transpiring.foreign.punctures.”

Need to give helicopter landing zone coordinates to your rescue site in the trackless snow of British Columbia? Your app can tell you: “pointer.pirate.talkers.” The heli pilot, equipped with the what3words app, knows exactly where to go.

The app is used by thousands of businesses, including search and rescue and other emergency services.

What3words boasts that its promoters call it “fiendishly clever” and “the app that can save your life.”

But what3words has many critics. Drawbacks, they say, are:

- Similar names. Similarly-named squares are close to each other—sometimes less than a mile apart, which might cause confusion. In England, stream.rivers.abode and steam.rivers.abode are some 50 km apart; if a call isn’t heard correctly, the regional emergency service could end up going to the wrong location.

- Not open-source. The technology behind W3W is held by a private company. It’s not open for inspection. If the organization ceases operating without passing along its proprietary code, the system can instantly become useless.

- Not tectonically adaptable. When an earthquake or gradual tectonic activity shifts land masses, street addresses stay the same, but W3W’s codes change (lat/long coordinates do also).

- Not linguistically universal. A location has one code in English, and a different one in French—48 different names in the 48 languages W3W uses, all for the same spot. And for the thousands of other languages, W3W doesn’t have codes at all.

- Phones can already send location data. Many modern mobile phones can already transmit geolocation data through the Advanced Mobile Location (AML) specification. (However, many emergency services currently can’t use that data.)

- Homophones. Dozens of words that sound very similar or identical appear to exist in W3W’s wordlist, such as pokey/poky, choral/coral, and collard/collared. Plurals are also a problem: deep.pink.start and deep.pinks.start (try saying them aloud) are both in an Arizona park, but about a half-mile apart. This can send rescuers to the wrong location.

What3words can be useful—and potentially life-saving. It’s not perfect, however—and to be fair, no geolocation system is, in all circumstances.

Google Maps: Don’t Use It Unthinkingly

From the advent of phone-based mapping systems to the current day, there are many stories of GPS-following drivers blithely driving into lakes or getting stuck in the wrong place.

The same risk applies to electronic map users in the wilderness.

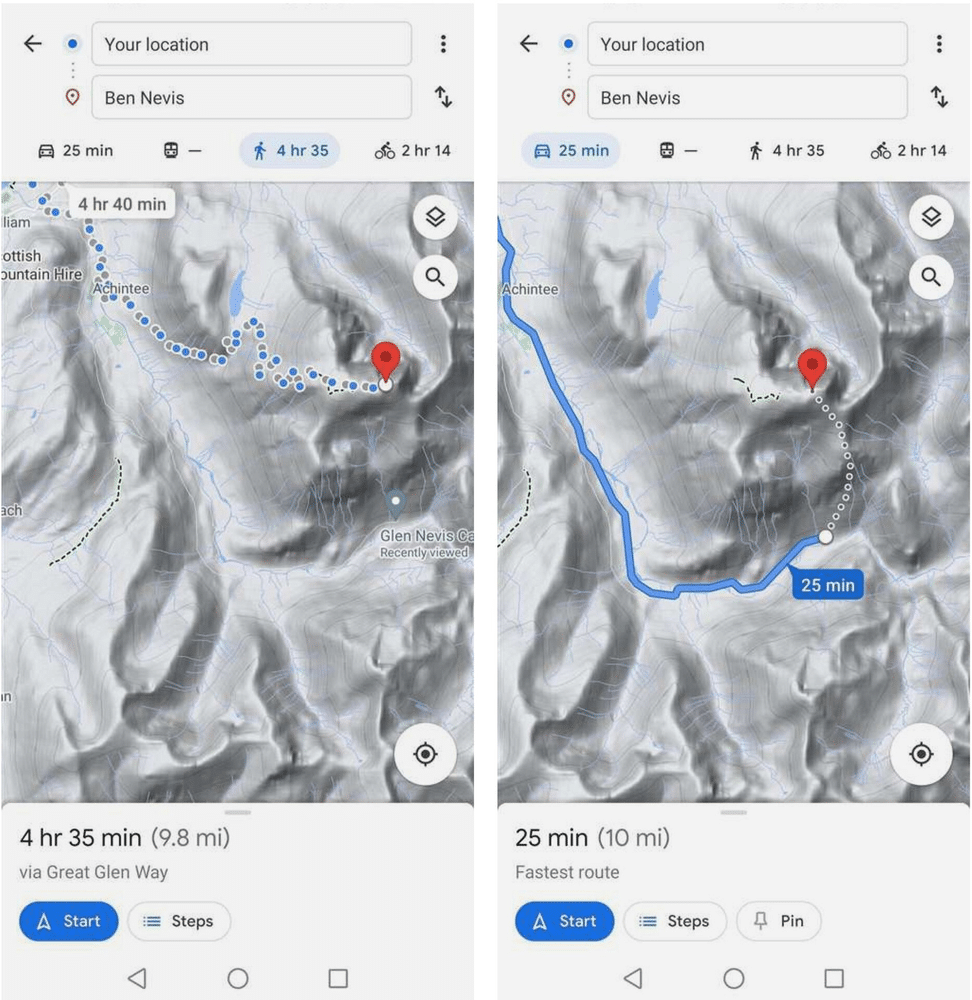

Google Maps came under recent criticism from Mountaineering Scotland for seemingly encouraging hikers to take a dangerous off-trail route up Scotland’s highest mountain, Ben Nevis.

Asking Google Maps for driving directions to Ben Nevis directed drivers to the parking lot near the summit, and showed a dotted line from there leading straight up to the peak—a “potentially fatal” route up very steep, rocky, and pathless terrain.

Mountaineering Scotland said other mountains had the same problem, with the Google Maps walking route for the mountain An Teallach taking people over a cliff.

The rescue agency’s attempts to contact Google to correct the mistake were initially fruitless. But on July 20, after the story made headlines, Mountaineering Scotland reported that Google fixed the Ben Nevis route issue.

Google claimed the dotted line on the map from the trailhead to the peak indicates the distance to the top, not a walkable trail.

Mountaineering Scotland encourages hikers to double-check map information with reliable sources before setting out.

Bringing a map and compass are recommended for Ben Nevis as well.

As with what3words, then, we can see Google Maps not as a panacea, but as one tool that can be useful when used in an appropriate way in appropriate circumstances. Neither should not be relied upon without other sources of information, and a recognition that good judgment and critical thinking skills are important too.

The issue of electronic locating technology on Ben Nevis also came up last month, after a 24-year old woman died hiking on that mountain. The UK government’s Test and Trace app, used for COVID-19 contact tracing, was suggested as a tool that could be used at trailheads to identify hikers who had been on the trail at the same time as the missing person, and who might be able to provide valuable information.

Although that particular idea has yet to be implemented, authorities found a route-planning app the hiker had downloaded, which helped them identify her hiking route and determine where to search for her.

Other Options Abound

Many alternatives to what3words exist, including open-source electronic options and the classic map and compass.

Alternatives to Google Maps exist as well, such as Windy Maps.

Telecom devices like satellite phone/message handsets and emergency beacons for marine, aviation and personal use can be helpful when used appropriately.

A useful safety principle is that of redundancy: having backups in case the first approach doesn’t work. While what3words and Google Maps can aid in some circumstances, bringing along a good map (perhaps with a compass)—and knowing how to use them—can be invaluable. Paper maps and magnetic compasses never run out of batteries or lose their GPS connection, after all.

And wildland mangers and rescue agencies encourage those who travel outdoors to learn the basics of outdoor safety, including how to prepare, what to pack, and how to respond in an emergency.

In addition to bringing electronics on trail, they say, it’s always important to pack your common sense.