Darrel McCutcheon, Jr., was described as a sweet and caring child with a bright smile and personality. A creative 13-year-old, he loved robotics and basketball. He was excited about a future in science, technology, engineering, and math.

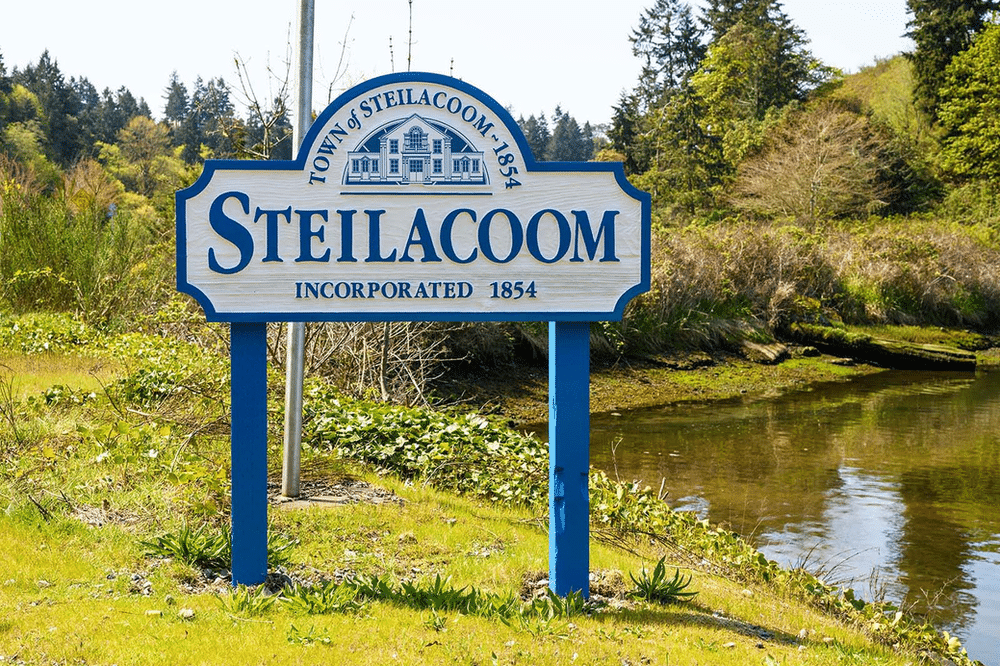

His family had recently moved to Washington state for work, and his parents enrolled him in a summer camp program operated by a community center run by the small town of Steilacoom.

On July 15, 2022, a summer camp employee drove “DJ,” as he was known, and eight other children by van to Florence Lake to go swimming. The employee left the campers, and drove away to pick up another group of youth.

Unsupervised, some of the kids got into the water and tried to swim to a platform about 35 feet from shore.

DJ was not given a swim test, nor did camp staff provide him with a PFD (life jacket). He had never swum in open water before.

DJ began having difficulty in the deep water. He began to bob up and down, and asked for help, according to representatives for his family. He then stopped moving and went underwater.

A person walking on the beach noticed the emergency, and swam out to where DJ was, in water about three meters (10 feet) deep. He made dive after dive, looking for DJ. Finally he spotted the child’s arm, and grabbing DJ’s hand, pulled him to the surface.

The bystander brought DJ to shore and began CPR.

DJ had been under the water about six minutes. He was airlifted to a nearby hospital, where he was pronounced dead.

Release of Liability Waiver Ineffective

DJ’s parents sued the town of Steilacoom for gross negligence.

The town attempted to have the case thrown out of court. Steilacoom said that DJ’s mother signed a waiver accepting any risk, including death, of her child participating in activities, including water activities.

The family’s legal team argued that the release didn’t describe any situations where campers would be taken to open water.

They also noted that the camp program appeared to violate the policy in a staff training manual saying that campers “must be under the supervision of a staff person at all times during program hours.”

The judge found that a duty to act and the breach of that duty had been established. The family’s attorney stated that this meant the town was negligent.

The wrongful death lawsuit was settled before the trial began. Steilacoom agreed to pay USD 15 million—more than half of the town’s annual USD 24.5 million budget—to settle the case.

The money will be drawn from Steilacoom’s insurance funds.

Lapses

Most drowning deaths are preventable.

In this case, a group of about 20 kids were scheduled to be transported to the lake to go swimming.

The camp program’s van did not have the capacity to take all campers at once, so camp staff decided to drop some kids off, drive back just over a mile to pick up the rest, and bring the remaining kids to the lake.

This is what occurred, leaving one group of campers unsupervised for some 10 to 11 minutes.

According to the complaint, the counselor who drove the van knew that there were no lifeguards on duty at the lake.

A third camp counselor was supposed to accompany the group, but, according to the lawsuit, the camp was unable to find one.

The town’s attorneys stated that the camp counselor had instructed the campers at the lake not to get in or go near the water.

The court appeared to find that the camp’s staffing difficulties and limited vehicle capacity were not sufficient justification for leaving kids—who were going to the lake for a swim—unsupervised at the lake.

Prevention

Are there standards for how camps can appropriately conduct water activities?

There certainly are.

The 2020 drowning of another 13-year-old boy, at a camp in South Africa, illustrated the need for improved water safety standards and practices in that country.

But in the USA, where this incident occurred, the American Camp Association publishes well-developed standards for camp safety, including risk management guidelines for water-based activities. The standards are employed by thousands of camps nationwide.

ACA’s highly detailed water safety standards cover swimmer accounting systems, aquatic supervision ratios, aquatic lookout training, swim testing, lifeguard certification, aquatics supervisor qualifications, lifeguard positioning for observation and intervention, location-specific swim area rescue skills, written aquatic safety regulations, aquatic-specific emergency procedures, aquatic equipment management, aquatic hazard management, aquatic site boundary establishment, and PFD use, in addition to general standards regarding risk management plans, safety briefings, missing person procedures, screening procedures, emergency response, and emergency plan rehearsal.

The total cost to a camp (including staff time) to become ACA-accredited can be some thousands of dollars. It’s not necessary to complete the full accreditation process to understand and follow ACA’s water safety guidelines, however. ACA’s Accreditation Process Guide describing camp safety standards can be purchased from ACA for USD 89.95.

For the cost of settling the wrongful death lawsuit, Steilacoom could have purchased the safety standards 166,759 times.

Also in the USA, the Commission for Accreditation of Park and Recreation Agencies (CAPRA) of the National Recreation and Park Association publishes accreditation standards which require agencies to have risk management technical expertise and implement safety training, incident prevention activities, risk management strategies, and safety rules, with external auditors to evaluate whether efforts are sufficient.

In other locations, camp associations publish detailed safety guidelines. For example, the Alberta Camping Association accreditation standards require that at least one lifeguard be on activity duty, whether participants are swimming, on a dock, or on shore. The standards additionally state:

- Camps operating waterfront programs must assess the swimming skills of the campers before the campers are allowed to participate in any waterfront activities.

- Camps must properly secure swimming areas when there is no lifeguard on duty.

Like CAPRA’s standards, the Alberta Camping Association’s standards are available for free, online.

Why the town of Steilacoom, a quiet and bucolic seaside community of some 6,600 persons, did not appear to follow widely recognized and accessible camp and waterfront safety guidelines is unclear.

Making Meaning

DJ’s parents had struggled for years with infertility, their attorney said. They called DJ, who was their only child, their “miracle baby.”

Reflecting on the lawsuit, the attorney said, “It’s never been about the money…this has always been about justice for DJ.”

No amount of money will be able to bring back the only child of Tamicia and Darrell McCutcheon Sr., or assuage the terrible grief and deep, piercing pain felt by DJ’s parents and loved ones.

Tamicia wrote, “When the casket close[s] and the call[s] stop…the PAIN is still there. Grief has no time limit.”

But DJ’s parents have a plan to make meaning of the terrible loss of their son, and through this find a measure of closure.

In doing so, they follow in the footsteps of other grieving parents, such as George Schwimmer, whose son drowned on a kayaking trip, and who advocated for camp safety reform.

Tamicia and her husband developed a plan to use settlement monies to start a nonprofit that will promote summer camp aquatic safety, and bring education and accountability to daycares and camps.

Their lawyer said, “The most important thing for them is to never have this happen to another child.”