Models and Theories of Safety Management in Remote Outdoor Settings

The young woman screamed and clutched her shoulder. She was standing in knee-deep water by a beach at the base of a rapids, where members of her canoeing expedition were practicing whitewater paddling maneuvers.

She collapsed into the water and began having a seizure. The trip leaders rushed to her side and dragged her to shore. Raised red blotches began appearing on her abdomen and legs. She began scratching at the swollen itchy hives—so fiercely that a trip leader restrained her arms, fearful she would draw blood with her fingernails.

Her breathing rate was six times normal. Her eyelids swelled so massively they drooped over her eyes, which could no longer fully open. She explained she had been stung by a wasp, and had a history of severe reaction to insect stings.

This was the life-threatening allergic reaction, anaphylaxis. But on a remote river far from a road and miles from any town, a hospital was nowhere nearby.

Her trip leaders, though, were trained in wilderness medicine, and had medication readily available. They injected her with epinephrine, and provided antihistamine. Soon her breathing slowed, her hives diminished, and the swelling went down.

The expedition member was evacuated to a clinic, where she was evaluated and cleared to return to her wilderness trip, which she did the same day.

What could have been a catastrophe was resolved quickly and smoothly. Well-trained instructors, adequate emergency supplies, and pre-established evacuation plans helped ensure effective management of the incident.

Although the severe allergic reaction wasn’t prevented from occurring in the first place—an outcome preferable to even the best emergency response—the emergency was handled well: an example of successful wilderness risk management.

Overview

Let’s now take a closer look at the elements of wilderness risk management that help prevent incidents from occurring, and minimize losses when mishaps take place. In the following sections, we will:

- Explain what we mean by the term “wilderness risk management,”

- Provide a summary of general approaches to management of risk,

- Explore models explaining why incidents occur, with an emphasis on those which employ complex socio-technical systems theory,

- Discuss uses of and problems with risk assessments, and

- Outline opportunities to learn more about wilderness risk management.

What is Wilderness? What is Risk Management?

The term ‘wilderness’ has many meanings. In the context of wilderness rescue and emergency medicine, wilderness has been in the past applied by some to refer to situations where access to definitive medical care is two or more hours away.

A strict time-based delineation has at this point, however, largely been abandoned. We might instead consider ‘wilderness’ to indicate remote outdoor settings—such as deep in the mountains, desert, forests or ocean—which may involve extreme environments, limited or improvised equipment, and delayed or prolonged transport.

Much of “wilderness” risk management can be applied to settings that are not in remote, wild natural areas. Programs that provide experiences in local parks, on a campus-based ropes course, at a summer camp setting, on a local lake, or at a service-learning site in a rural village can apply the same safety principles to managing the risks of their program.

Risk management, as well, has myriad definitions. For our purposes, we can consider ‘risk’ to be the possibility of undesirable loss, and risk management to indicate a systematic, intentional, and ongoing process of maintaining risk at a socially acceptable level.

General Approaches to Risk Management

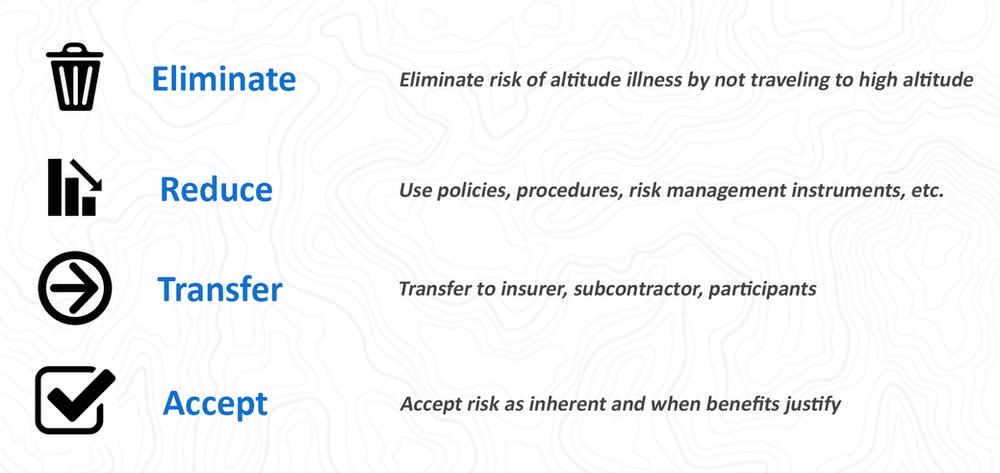

In risk management theory, there are four widely accepted approaches to managing risks. These are to eliminate risks, reduce risks, transfer risk to other parties, or to simply accept some level of risk.

Wilderness risk management, like any other form of safety management, seeks to employ all four of these approaches.

Systems-Informed Incident Causation Models

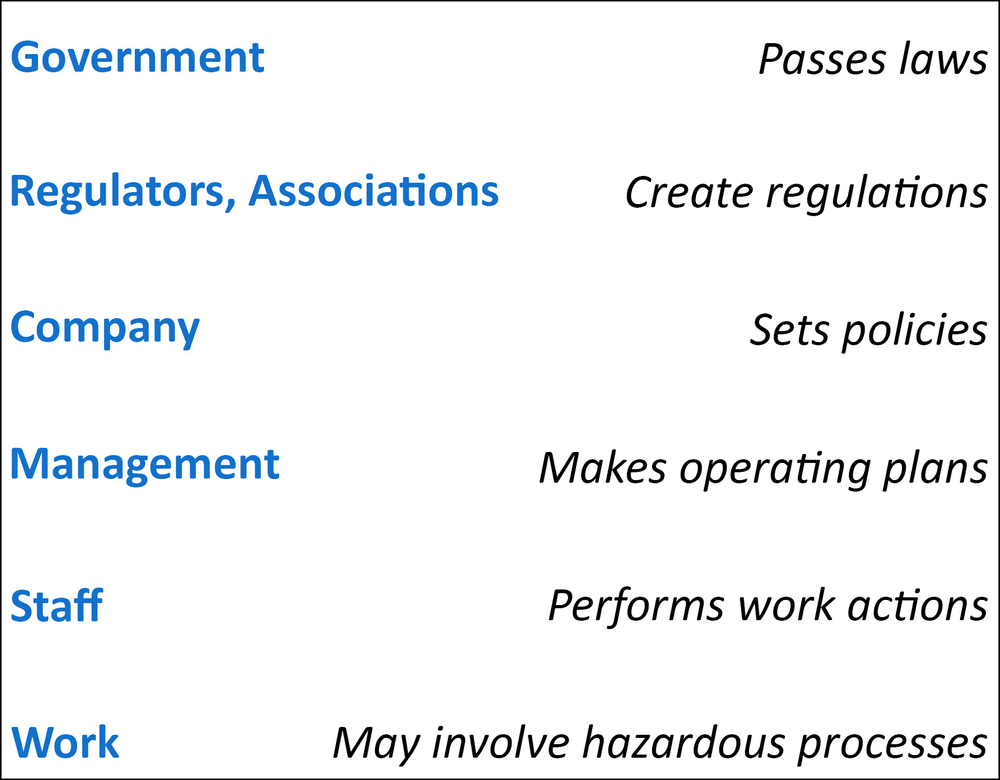

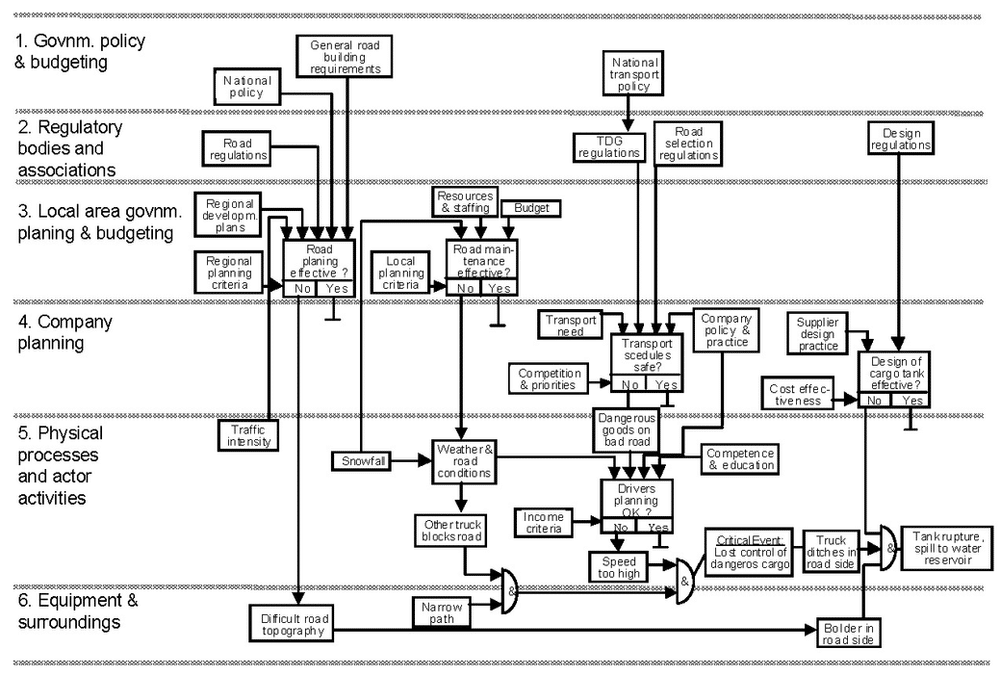

The Accimap approach to understanding and addressing factors leading to incidents was developed in 1997 by the Danish professor Jens Rasmussen and others. Rasmussen argued that causal factor areas—such as deficient legislation or poor operator training—should not be evaluated in isolation.

He noted that typically, government affairs were analyzed by political scientists and economists, for example; company operations by management consultants; staff behavior by industrial-organizational psychologists, and work actions by mechanical engineers.

Rasmussen proposed that instead, all elements should be considered together, as part of a complex socio-technical system that leads to an incident.

Using this systems-informed model, a map of specific factors in each element that led to a particular accident could be created. This would illuminate the detailed specifics that contributed to an incident.

In the Accimap above, road-building requirements, national transportation policy, road maintenance, cargo tank design, traffic intensity, snowfall, driving speed, and a road-side boulder were all considered as factors leading to the incident.

Another model designed to look comprehensively at incident causes is the Human Factors Analysis and Classification System, or HFACS. This was developed for the US military, which had noted that “many investigators look only as far as the person(s) involved in the mishap” and sought a tool to help increase investigation accuracy. HFACS offers a practical model that looks at factors first described by James Reason: organizational influences, unsafe supervision, preconditions (like the physical environment, tools, communications, and individuals’ mental states), and unsafe acts.

The Systems-Theoretic Accident Model and Processes, or STAMP, also incorporates elements of Rasmussen’s model, and views safety as a control problem, focusing on addressing inadequate control measures, and incorporates constraints, control loops and process models as key elements.

Other models abound. The Meyer/Williamson Accident Matrix, well-known in outdoor circles but criticized as taxonomically limited following recent theoretical advances, sees outdoor accidents principally caused by potentially unsafe conditions, potentially unsafe acts, and potential errors in judgment. The 5M model (an expansion of the man-machine-medium model introduced in the 1940’s, also described as person-equipment-environment) looks at member (people), machine (tools/equipment), and medium (environment), and adds mission (the purpose of the activity), and incorporates management as an overarching influence. Numerous variations of this model exist, including the PEEP model (people, equipment, environment, process) and its cousin PEEPO, adding organization as a factor. Although the 5M and PEEP models are generally designed for industrial applications, they are employed in wilderness risk management, for example by Outward Bound Singapore.

The Sometimes-Missing Element: Including Complexity in Complex Systems Models

The models described above are an advance on previous models which focus blame on the individual person closest to the incident, rather than employing just culture.

They are also superior to models which see all incidents as the end result of a linear chain of events, such as the now-outdated “domino theory” of accident causation.

However, models which simply encourage users to look at a wide variety of potential factors—such as people, equipment, the environment, organizational management, government and social factors—are missing a key element in a truly systems-informed approach to understanding why incidents occur.

This is the idea of complexity in complex socio-technical systems (such as led outdoor activities).

Complex systems—from a backpacking expedition to a nuclear power plant or the issue of global climate change—have these characteristics:

- Difficulty in achieving widely shared recognition that a problem even exists, and agreeing on a shared definition of the problem

- Difficulty identifying all the specific factors that influence the problem

- Limited or no influence or control over some causal elements of the problem

- Uncertainty about the impacts of specific interventions

- Incomplete information about the causes of the problem and the effectiveness of potential solutions

- A constantly shifting landscape where the nature of the problem itself and potential solutions are always changing

A key characteristic of complex systems is that observers—such as the wilderness trip leader or the outdoor program manager—do not have full awareness of all the factors that might lead to an incident. Participant fatigue, trip leader judgment error, upcoming trail conditions, potentially hazardous bystanders, heavy upstream rainfall, malfunctioning equipment, organizational financial pressures—no person has complete knowledge of the status of all these potential contributing factors.

Furthermore, the best understanding of how incidents occur includes the idea that incidents are typically due to a number of factors, and that those factors interact in ways that are impossible to predict and may not be fully understood.

Managing the risks of climate change—in outdoor programs or elsewhere—is an example of risk management in a complex system with immense challenges to understanding and effectively mitigating risks.

What is the consequence of this? Wilderness risk managers—and safety managers in any context—must anticipate that risk management systems will break down. But it may be impossible to accurately anticipate where, and when, and how that breakdown will occur.

Therefore, risk management systems must build in resilience to unexpected breakdowns.

This means that wilderness risk managers should build resilience into their management systems to include:

- Extra Capacity, such as available backup field staff, replacement equipment, pre-developed contingency plans, and staff trained beyond standard requirements, such as a flatwater paddlers having swiftwater rescue skills

- Redundancy, for example multiple trip leaders per group, multiple emergency telecom devices, and multiple emergency evacuation routes

- Integrated Safety Culture, which means fostering a balance between rules-based safety emphasizing following documented procedures, and ‘managed safety,’ where personnel use their own judgment to adapt to unique situations

- Psychological Resilience, where a positive attitude towards addressing and overcoming challenges is built

Wilderness risk managers should also be supported to consider all the factors that may contribute to an incident. Incident reporting systems such as that of Australia’s UPLOADS Project, for instance, structurally encourage users to consider a wide range of factors when analyzing outdoor safety incidents.

And systems-informed strategic planning techniques can help ensure that wilderness risk managers are building systems thinking in all levels of program operations. Analysis of aggregated incident reports to uncover potential and emergent patterns and trends is an example. The “pre-mortem” technique of anticipating a hypothetical critical incident and analyzing contributing factors can elicit creative thinking to surface issues that might otherwise have gone unaddressed.

Safety Models: Ever-evolving and Imperfect

Theoreticians continue to churn out new models, which often build on the frameworks established by preceding models.

Lumpers and splitters will combine and divide causal factors into any number of separate categories, with no particular taxonomy being inherently superior to another.

No model, by definition, is a perfect representation of reality—they are, by nature, simplifications. Each model has strengths and areas of relative weakness.

And each model has situations where it will perform better than in other situations. For example, complex models are more well-suited to highly-trained career safety managers whose entire job revolves around understanding and applying risk management knowledge to workplace settings, where a simpler model may be easier to digest by a teenage camp counselor leading a hiking trip.

The Risk Domains Model for Outdoor Safety

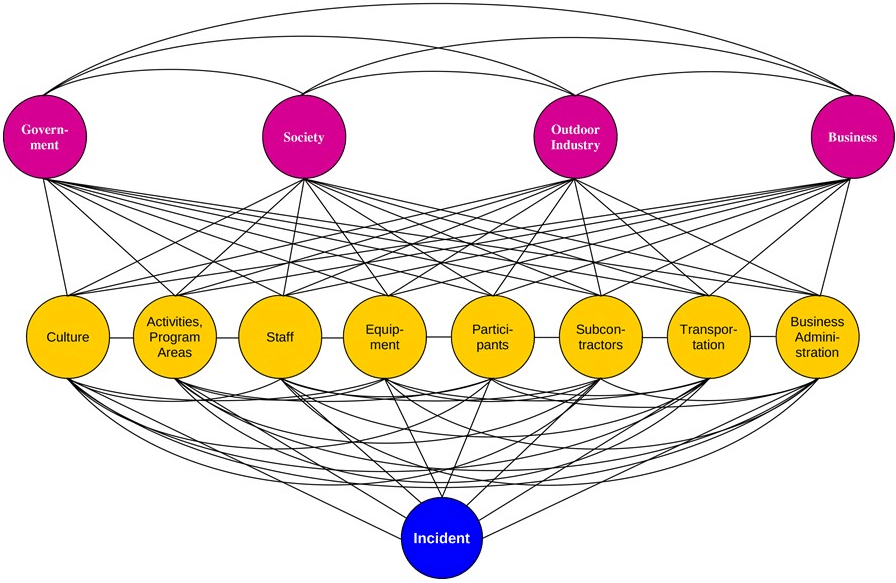

A model that attempts to provide a systems-based framework for managing risks in wilderness expeditions as well as non-wilderness outdoor, travel-based, experiential and adventure programs is the Risk Domains model.

Here we see eight “direct risk domains,” in yellow. These represent areas, such as staff and equipment, where risks may reside.

Four underlying risk domains, in fuchsia, illustrate areas that may indirectly influence wilderness risk management. The presence or absence of government safety regulations, or a robust accreditation scheme developed by the outdoor adventure industry, are examples of factors that can influence safety outcomes on the ground.

Critically, the interactions—some predictable, others unanticipated—between various domains, leading to an incident, are illustrated.

Specific policies, procedures, values and systems to manage the risks that are identified as existing in each risk domain, for any given program, should be instituted to help ensure that risks do not exceed a socially acceptable level.

For instance: a policy requiring safety briefings before each activity, a procedure for proper belay technique, an organizational culture valuing safety, and a medical screening system can manage wilderness risks.

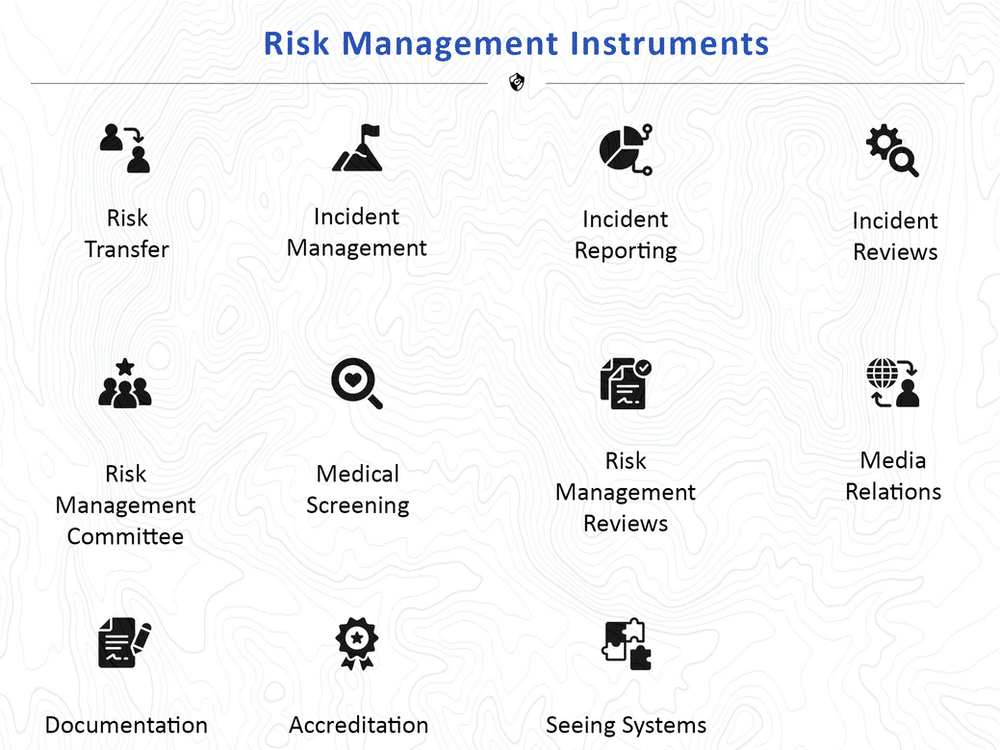

Beyond these specific policies, procedures, values and systems, broad-reaching risk management tools, or instruments, can be employed to manage risks across multiple or all domains. The Risk Domains model incorporates 11 such instruments:

For example, risk transfer includes the use of liability insurance and liability waiver forms. Incident reviews and risk management reviews seek to retroactively and proactively consider how to prevent future incidents from occurring. And ‘Seeing Systems’ refers to the crucial element of applying complex socio-technical systems theory to the field of wilderness risk management, as discussed above.

More information on systems-informed approaches to managing risks—referred to by terms including “Safety-II” in the Safety-I/Safety-II construction, guided adaptability, and Safety Differently—can be found here.

Risk Assessments: A Cautionary Tale

In certain parts of the world, particularly current or recently former members of the British Commonwealth, the use of risk assessment spreadsheets is common in wilderness risk management.

These spreadsheets can serve a useful function in highlighting relatively obvious and predictable risks—such as motor vehicle accidents, capsizing in whitewater, or lightning strike.

They have a legitimate use in developing policies and procedures to guard against these easily anticipated risks.

But they do not do a good job of addressing the risks that complex socio-technical systems theory tells us are a significant source of injury, illness, and other loss in wilderness programs.

For example, a multiple drowning in 2006 on an outdoor education school trip was attributed to a large constellation of causes, including defects in the national weather service, employee turnover, workload, financial pressures, lack of equipment, and inadequate practice of emergency plans.

It’s not realistic to expect that a spreadsheet listing possible causes—and all potential combinations of such causes—could anticipate such a mix of factors.

Therefore, the presence and use of risk assessment spreadsheets, no matter how detailed, should not be relied upon as evidence of good risk management in wilderness-based, travel, adventure, outdoor or other experiential programs.

Additional Resources

A number of opportunities to further explore wilderness risk management are available.

Conferences

A variety of conferences provide workshops on safety considerations for wilderness and related programs.

The Core Risk Conference, affiliated with UK-based Remote Area Risk International, specializes in content on wilderness travel and other remote operations.

The Wilderness Risk Management Conference, established in 1994 following the death by rockfall of a student on a NOLS course, provides a variety of workshops on mitigating risks found in wild places.

The National Outdoor Education Conference of Outdoor Education Australia, the Outdoor Forum for South East Asian Schools, the annual conference of the Association for Experiential Education, and Institutes held by the Independent Schools Experiential Education Network, among other conferences, offer tracks or workshops on wilderness or outdoor safety-related topics.

The Centre for Human Factors and Sociotechnical Systems, a research center affiliated with Australia’s University of the Sunshine Coast, offers symposia and other resources on safety science for outdoor and other fields.

Conference workshops have been criticized for offering piecemeal fragments of risk management theory and practice, rather than a comprehensive training experience. They nevertheless can provide valuable networking and professional development opportunities.

Books

A number of texts on risk management provide theories and information that can be applied across industries. These books, such as The Field Guide to Understanding ‘Human Error’ and other titles by Sydney Dekker, Safety-I and Safety-II by Erik Hollnagel, and Human Factors Methods and Accident Analysis by Paul Salmon et al. can tend towards the academic and the large-enterprise context, but offer useful insights into risk management theories and models.

A sprinkling of outdoor safety-specific texts is available. Among the top titles:

Outdoor Safety: Risk Management for Outdoor Leaders, published by the New Zealand Mountain Safety Council, is easy to read, comprehensive, and provides concise and helpful guidance for both the New Zealand and global context.

Managing Risk: Systems Planning for Outdoor Adventure Programs, written by well-established Canadian outdoor experts, offers well-developed content on systems-informed safety practice for adventure-based organizations.

Lessons Learned : A Guide to Accident Prevention and Crisis Response, published in 2002, is a classic in the outdoor risk management literature, along with its companion, Lessons Learned II.

Risk Management for Outdoor Programs: A Guide to Safety in Outdoor Education, Recreation and Adventure offers an in-depth view of risk management theory, case studies, and practical guidance for outdoor, experiential, and travel-based programs.

Trainings

Remote Area Risk International offers module-based safety trainings including on travel risk management, risk assessment, emergency plans and disaster response for wilderness professionals from their UK location.

The Royal Geographical Society offers an Offsite Safety Management two-day curriculum, also delivered by a variety of third-party providers in the UK and elsewhere.

The National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) offers a 16-hour Risk Management Training for Administrators, with online or in-person options.

A variety of colleges, including Lees-McRae and Southern Oregon University, also offer outdoor risk management courses, typically as part of degree programs.

Viristar provides a Risk Management for Outdoor Programs training, a 40-hour online course delivered over four weeks, which incorporates self-study, group projects, and a comprehensive organizational self-assessment.

In Conclusion

The wilderness expedition member who experienced a frightening case of anaphylaxis in the field returned to her group. She enjoyed her next two weeks of whitewater paddling through magnificent desert canyons, rock climbing up jagged basalt cliffs, and adventurous hikes through beautiful wild landscapes. The remainder of her trip was full of exciting outdoor adventures—but thankfully was medically uneventful.

We’ve now seen some of the principles of wilderness risk management that help prevent incidents—or reduce their probability and severity—on trips in wild and remote natural settings. These include:

- Understanding wilderness risk management as a systematic, intentional, and ongoing process, for programs taking place in remote outdoor settings, of maintaining risk—the possibility of undesirable loss—at or below a level that’s socially acceptable.

- Recognizing four overall general approaches to risk management: eliminating risks entirely, for example by not conducting certain activities; reducing risks, for instance by implementing sound safety procedures and a good safety culture; transferring risk to others, such as to insurance agents or third-party providers, and judiciously accepting risk in certain circumstances as an inherent part of an outdoor adventure.

- Exploring models that work to explain why incidents occur. This includes recognizing that outdoor safety mishaps take place because of risks in direct risk domains—such as safety culture, transportation, subcontractors or participants, among others. And underlying risk domains—government, society, the outdoor industry and corporate interests—have an indirect influence too. Specific policies, procedures, values and systems, and broad-based risk management instruments, can mitigate these risks. And critically, using resilience engineering and other steps to manage the unpredictable risks that emerge from a complex system is an essential component of any good risk management model.

- Appreciating that risk assessment spreadsheets can be useful in managing self-evident frontline risks, but are not useful for addressing emergent risks in complex systems—so their presence alone should not be taken to indicate a comprehensive, high-quality risk management infrastructure.

- Taking opportunities to learn more about wilderness risk management, as theories, models, and best practices continually evolve and improve.